Introduction

The relationship between lack of food security and mental health challenges forms a ‘syndemic’, where these issues converge and interact within populations and are often heightened by underlying social and structural determinants.[1] This syndemic is marked by the complex connections between food insecurity and negative mental health outcomes, such as increased psychological distress, depression, and anxiety. Chronic food insecurity worsens these mental health challenges, creating a bidirectional relationship that hinders individuals’ ability to access adequate nutrition, thus perpetuating a self-reinforcing cycle. Key aspects of the relationship between food security and mental health include interconnected health outcomes, the influence of nutrition on cognitive development, gender-based inequalities, and the compounded effects of conflict and crises. Together, these factors highlight the multifaceted nature of this public health challenge. Addressing the intricate connections between food security[a] and mental health is crucial to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2 (Zero Hunger) and 3 (Good Health and Well-Being).[b]

According to the 2024 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, approximately one out of every 11 people worldwide is affected by chronic hunger due to food insecurity.[2] This indicates that global attempts to eliminate hunger[c] and food insecurity by 2030 are off-track. Global hunger, affected by conflicts, climate change, rising food prices, and inequalities, could be stabilising; 815 million people were impacted in 2017 compared to 333 million people in 2023.[3] This improvement can be attributed to interventions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the war in Ukraine, which affected global grains trade, has gradually slowed this improvement.[4] Additionally, the conflict in Gaza could create increasing global food insecurity.[5] Between 2019 and 2022, global hunger rose by 122 million, while food insecurity saw a 20-percent increase.[6] Aside from local food shortages, conflicts disrupt global food systems, agricultural output, and supply chains by decreasing production, limiting access to vital resources such as fertilisers and farm chemicals, and raising prices, presenting major obstacles to food security on a global scale.[7]

Mental Ill Health and Food Insecurity: A Circular Relationship

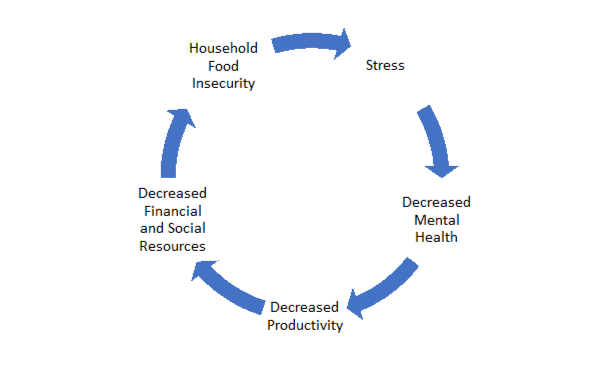

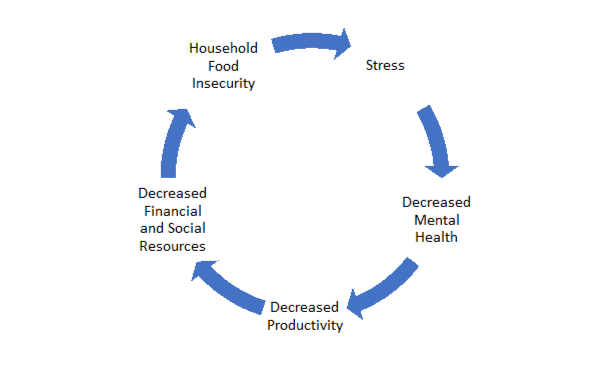

Food insecurity and negative mental health are interconnected in a complex way (Figure 1). For example, food insecurity can lead to depression, while depressive symptoms can, in turn, worsen food insecurity. There is a strong correlation between the severity of food insecurity in households and the likelihood of negative mental health outcomes.[8] One way that food insecurity affects mental health is through stress, especially the anxiety arising from uncertainty about access to adequate food. Other factors can intensify the negative effects on mental health, including genetic predispositions, social determinants, and personal experiences such as a history of trauma or inadequate coping mechanisms.

Figure 1: Circular Relationship Between Mental Health Decline and Food Insecurity

Source: Calgary Food Bank[9]

The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community.”[10] Food insecurity is associated with poorer mental health outcomes and specific psychosocial stressors across global regions independent of socio-economic status.[11] It is linked to early growth delays, impaired cognitive development, and lower scores on mental health measures, primarily because it leads to micronutrient deficiency.[12] Women are disproportionately affected by food insecurity, leading to increased vulnerability to mental stress.[13] Mental health issues in mothers and children are more prevalent when mothers experience food insecurity—a stressor that could be alleviated through social policy interventions.[14] Children in food-deprived households often experience aggressive behaviour and psychological stress from their parents, resulting in negative behaviour in children.[15] Severe child hunger is a critical public health issue with implications for both physical and mental health, including an increased likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research highlights its independent association with chronic illnesses, anxiety, depression, and internalising behaviour issues, even when considering environmental, maternal, and child-related factors.[16] Moreover, severe hunger is strongly linked to homelessness, low birth weight, and exposure to traumatic life events, which increases vulnerability among affected populations.

Indeed, the connection between food insecurity and mental health outcomes is well documented. A 2018 study in Ontario found that 40.4 percent of individuals who used professional mental health services faced severe food insecurity over a 12-month period.[17] These individuals often had to make sacrifices such as reducing their food consumption to stretch their limited incomes. In contrast, only 15.6 percent of those who were food secure reported seeking mental health support at similar rates.[18]

A review study has confirmed the connection between food insecurity and mental anguish and reported key areas to explore further, including mental health signs (eating disorders and suicide), surrounding factors (environmental and personal influences), and limited access to food.[19] Research on the connection between food insecurity and mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that individuals experiencing food insecurity are at a heightened risk of anxiety (257 percent) and depression (253 percent).[20] A case study in London examined the experiences of families who rely on food banks.[21] Participants reported chronic stress due to the uncertainty around food availability, which heightened their anxiety about meeting other basic needs such as housing and healthcare. Qualitative interviews revealed that constant worries about accessing food disrupted daily routines and negatively affected family relationships. Parents often felt guilt and shame for not being able to provide sufficient nutrition for their children, which further intensified their mental health challenges.

A link has been found between health, food availability, and the emotional well-being of youth across 160 countries.[22] The absence of essential commodities, including food sources, access, availability, and nutritional status, can adversely affect mental well-being.[23] In Africa, systematic reviews indicate that the effects of food insecurity on mental health are particularly pronounced among older adults and women.[24] Additionally, findings from studies in Portugal demonstrate that women living in food-insecure households exhibit higher levels of anxiety and depression.[25] The rise in food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected marginalised groups, increasing their vulnerability to negative mental health outcomes.[26] The emergency state of the pandemic emphasised the critical necessity for a comprehensive and systemic global response, as COVID-19 exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities, intensified structural inequities, and underscored the insufficiency of current policy frameworks in mitigating this complex crisis.

Socio-Economic Determinants of Food Security and Mental Health

The availability of nutritious food is closely linked to financial stability, with those who have steady incomes better able to afford healthy options, thereby reducing stress related to food insecurity. Conversely, financial hardship can increase anxiety and adversely affect mental health due to difficulties in accessing adequate food. Educational attainment also plays a role; higher income often correlates with better education which, in turn, facilitates access to resources that support food security and nutritional awareness. One study highlighted that food-insecure students often face stigma and shame, making them reluctant to seek support, which can lead to isolation and worsen mental health issues.[27] Conversely, social support can mitigate the negative impacts of food insecurity, as seen in a 2018 research in Sub-Saharan Africa.[28] Additionally, individuals with mental health challenges may struggle to navigate complex healthcare systems to meet their nutritional needs, facing barriers such as poor patient pathways and socio-economic disparities.[29]

Conflict is a critical determinant of both food insecurity and mental health, with far-reaching consequences for vulnerable populations, particularly youth and adolescents. In regions like Gaza, food insecurity is a pressing issue, with 59.4 percent of children affected.[30] This crisis is exacerbated by ongoing conflict, political instability, and limited resources, resulting in approximately 2.2 million individuals facing acute food insecurity, including 576,600 experiencing catastrophic hunger. In conflict zones such as the occupied Palestinian territories, the psychological impact of being economically disadvantaged often outweighs the actual metrics of food consumption, highlighting the need for stress-free access to food in high-stress environments.[31] In Yemen, the cholera epidemic[d] is exacerbated by chronic malnutrition, inadequate access to essential resources, and adverse climatic conditions.[32] The Democratic Republic of the Congo also exemplifies how prolonged conflict can lead to severe food insecurity and malnutrition.[33] An estimated 900,000 children are suffering from severe malnutrition within a larger context of 25.4 million acutely food-insecure individuals.[34] Decades of conflict and displacement have left 26 million people in extreme hunger, a situation worsened by climate shocks, Ebola outbreaks, and the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This ongoing instability contributes to mental health challenges, as the stress of food scarcity and related uncertainties weighs on individuals and families. In Afghanistan, decades of conflict have culminated in a humanitarian crisis characterised by dire food insecurity.[35] Following the government’s collapse in 2021, about 19.9 million people are now severely hungry, including four million malnourished women and children. Similarly, Yemen’s prolonged civil war has left 17 million individuals facing severe hunger, further aggravating malnutrition among already vulnerable groups. The ongoing crises in these regions contribute to instability, displacement, and poverty, severely impacting mental health.

The implications of food insecurity extend beyond individual health, contributing to systemic issues such as inequality and poverty. It perpetuates cycles of poverty by limiting access to nutritious food, which, in turn, leads to poor dietary quality, adverse health outcomes, diminished productivity, and increased mortality rates.[36] This dynamic exacerbates mental health challenges within affected populations. Research indicates that food insecurity intersects with structural inequalities, systemic racism, and various forms of oppression, resulting in chronic stress and limited access to critical resources, thereby reinforcing intergenerational cycles of disadvantage. Even in developed nations such as Ireland and the United Kingdom, barriers to accessing sufficient and healthy food perpetuate poverty cycles.[37] In developing countries, the absence of food security increases the likelihood of undernutrition, which is associated with elevated morbidity and mortality rates.[38]

Economic hardship and inadequate nutritional practices further heighten this risk, particularly impacting children in regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In countries like Mexico, factors such as climate-related disasters and economic disparities exacerbate food insecurity, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations, including women.[39] Empirical studies reveal that climate-induced events such as flooding can precipitate food insecurity and subsequent mental health issues among women, underscoring the necessity for enhanced financial protection and adaptive livelihoods.[40]

Moreover, food insecurity adversely affects community mental health by straining social relationships, reducing productivity, and amplifying social tensions.[41] Research indicates that households with caregivers who experience mental illness exhibit a higher susceptibility to food insecurity, particularly in low-income contexts. Conversely, robust community ties can serve as protective factors, mitigating threats to food security.

Sustainable Solutions, Global Efforts, and Policy Recommendations

To address food insecurity effectively, inclusive interventions that target socio-economic disparities must be implemented to facilitate equitable access to nutritious food. Such efforts are crucial not only for enhancing mental well-being but also for addressing broader societal challenges.

Food insecurity represents a public health concern that necessitates large-scale interventions. It is estimated that achieving food security for individuals currently facing severe food insecurity could lead to 8.9-16 percent reduction in the prevalence of six adverse mental health outcomes.[42] These outcomes include recent depressive thoughts, major depressive episodes within the past year, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, poor mental health status, and suicidal ideation over the last year. Providing adequate, nutritious food is crucial for addressing malnutrition, directly supporting mental health in multiple dimensions. Sufficient dietary intake ensures that individuals receive essential nutrients, including vitamin B, iron, and polyphenols, which are vital for optimal brain function. These nutrients contribute positively to mental health and cognitive performance at various stages of life and emphasise the role of nutrition in preventing and managing age-related cognitive decline.[43]

Despite challenges, scalable and sustainable intervention and innovative approaches can address the diverse needs of populations across regions. Social safety net programmes in West African countries are designed to offer direct assistance to vulnerable populations such as children, women, youth, and the elderly, assisting them in managing the effects of increasing food costs.[44] The European Union’s ‘Farm to Fork Strategy’ adopts creative methods[e] for enhancing food security.[45] Technology-based solutions such as mobile apps and data analytics are being used to improve food security by making food distribution systems more efficient, decreasing food waste, and providing timely access to nutritional information.[46]

Meanwhile, India’s electronic Public Distribution System (e-PDS) incorporates technology to streamline the distribution of subsidised food grains to beneficiaries, leading to more efficient food distribution and improved targeting of at-risk communities.[47] Urban community gardens and farms, for example in parts of France and in California, are also being used to provide accessible, locally sourced produce while promoting community engagement and utilising green spaces to improve mental health.[48] These gardens serve as nature-based solutions that support sustainability and overall well-being. Community gardens are found to have psychological, social, and physical health benefits, thus highlighting their potential for promoting public health in urban settings.[49]

The One Health approach, defined as “an integrated and unifying framework to sustainably balance and optimize the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems”, also provides a scientifically sound and interdisciplinary strategy for tackling complex global challenges.[50] By highlighting critical connections between climate change, food security, and mental health, the One Health approach could emphasise the intricate relationships among environmental changes, the emergence of zoonotic diseases, and agricultural practices. Rooted in cultural responsiveness and reflexivity, the One Health paradigm encourages a comprehensive understanding of these interconnections that enables identifying and addressing the feedback loops that can lead to negative outcomes.

Additionally, digital platforms and mobile applications provide mental health services, including stress reduction, therapy, and mindfulness practices, often integrated with nutritional information. Research indicates that mobile mental health applications targeted at college students are highly acceptable, feasible, and effective, highlighting their potential as valuable resources for university counselling services.[51] Additionally, developments in secure mental health applications have focused on enhancing emotion-regulation skills within a transdiagnostic framework. Furthermore, studies evaluating strategies to improve the implementation of school-based policies and programmes related to children’s diet, physical activity, and obesity have revealed a wide range of effect sizes.[52] Successful approaches include enhancing the nutritional quality of food served in schools, implementing effective canteen policies, and scheduling regular physical education sessions. Efforts to address deficiencies in medical nutrition education have proposed a collaborative framework to advance competency-based nutrition curricula, inter-professional education, and research in health professional training.

To break the cycle of food insecurity and mental ill health, interventions need to target mental health issues directly. Combining initiatives targeting both elements is crucial to promote sustainable development and meet the 2030 Development Agenda. Cooperation among countries, through organisations like the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), World Trade Organization (WTO), and the G20, can strengthen humanitarian efforts and help manage food supply-chain disruptions. Incorporating mental health assistance into current community initiatives, particularly in areas facing widespread food insecurity, can offer a holistic strategy. This calls for cooperation among mental health professionals, community leaders, and policymakers.

Endnotes

[a] The state of having reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.

[b] SDG 2 seeks to eliminate hunger, secure food availability, improve nutritional outcomes, and foster sustainable agricultural practices, while SDG 3 aims to promote health and well-being for individuals of all ages, highlighting the intrinsic connection between food security and mental health. See: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

[c] Periods when people experience severe food insecurity.

[d] The country is grappling with the most severe cholera epidemic of modern times, with over one million suspected cases and 3,000 fatalities, primarily driven by the protracted civil war that has undermined sanitation infrastructure and healthcare systems.

[e] Like precision agriculture to maximise yield while reducing environmental impact, machine learning & AI data driven technology to maximise agricultural management

[1] Ovinuchi Ejiohuo et al., “Nourishing the Mind: How Food Security Influences Mental Wellbeing,” Nutrients 16, no. 4 (2024): 501.

[2] UNICEF, “The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024: Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms,” 2024.

[3] World Food Programme, “Global Hunger Crisis,” October 24, 2024, https://www.wfp.org/global-hunger-crisis.

[4] Leal Filho et al., “How the war in Ukraine affects food security,” Foods 12, no. 21 (2023): 3996.

[5] Abdo Hassoun et al., “From acute food insecurity to famine: how the 2023/2024 war on Gaza has dramatically set back sustainable development goal 2 to end hunger,” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 8, 2024: 1402150.

[6] WHO, FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, and WFP, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023: Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum, Italy, World Health Organization, 2023.

[7] Ben Hassen et al., “Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war on global food security: towards more sustainable and resilient food systems?,” Foods 11, no. 15 (2022): 2301.

[8] Jessiman-Perreault et al., “The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults,” SSM-Population Health 3, 2017: 464-472.

[9] Calgary Food Bank, “Mental Health,” https://www.calgaryfoodbank.com/2022/mental-health/.

[10] Pan American Health Organization, “Mental Health”

[11] Andrew D Jones, “Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53, no. 2 (2017): 264-273.

[12] Maureen M Black et al., “Advancing Early Childhood Development: From Science to Scale 1: Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course,” Lancet 389, no. 10064 (2017): 77.

[13] R Srinivasa Murthy et al., “Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings,” World Psychiatry 5, no. 1 (2006): 25.

[14] Robert C Whitaker et al., “Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children,” Pediatrics 118, no. 3 (2006): e859-e868.

[15] Kevin A Gee et al., “Parenting while food insecure: Links between adult food insecurity, parenting aggravation, and children’s behaviors,” Journal of Family Issues 40, no. 11 (2019): 1462-1485.

[16] Linda Weinreb, “Hunger: its impact on children’s health and mental health,” Pediatrics 110, no. 4 (2002): e41-e41.

[17] Valeria Tarasuk et al., “The relation between food insecurity and mental health care service utilization in Ontario,” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 63, no. 8 (2018): 557-569.

[18] Lynn McIntyre et al., “Household food insecurity in Canada: problem definition and potential solutions in the public policy domain,” Canadian Public Policy 42, no. 1 (2016): 83-93.

[19] Candice A Myers, “Food insecurity and psychological distress: a review of the recent literature,” Current Nutrition Reports 9, no. 2 (2020): 107-118.

[20] Di Fang et al., “The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic,” BMC Public Health 21, 2021: 1-8.

[21] Claire Thompson et al., “Understanding the health and wellbeing challenges of the food banking system: A qualitative study of food bank users, providers and referrers in London,” Social Science & Medicine 211, 2018: 95-101.

[22] Frank J. Elgar et al., “Food Insecurity, State Fragility and Youth Mental Health: A Global Perspective,” SSM - Population Health 14, 2021: 100764.

[23] Lesley Weaver et al., “Unpacking the “black box” of global food insecurity and mental health,” Social Science & Medicine 282, 2021: 114042.

[24] John Paul Trudell et al., “The Impact of Food Insecurity on Mental Health in Africa: A Systematic Review,” Social Science & Medicine 278, 2021: 113953.

[25] Ana Aguiar et al., “The bad, the ugly and the monster behind the mirror-Food insecurity, mental health and socio-economic determinants,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 154, 2022: 110727.

[26] Jason M Nagata et al., “Food insufficiency and mental health in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 60, no. 4 (2021): 453-461.

[27] Lisa Henry, “Understanding food insecurity among college students: Experience, motivation, and local solutions,” Annals of Anthropological Practice 41, no. 1 (2017): 6-19.

[28] Muzi Na et al., “Does social support modify the relationship between food insecurity and poor mental health? Evidence from thirty-nine sub-Saharan African countries,” Public Health Nutrition 22, no. 5 (2019): 874-881.

[29] Tanja Schwarz et al., “Barriers to accessing health care for people with chronic conditions: a qualitative interview study,” BMC Health Services Research 22, no. 1 (2022): 1037.

[30] World Food Programme, “Palestine,” October 24, 2024, https://www.wfp.org/countries/palestine.

[31] Na et al., “Does social support modify the relationship between food insecurity and poor mental health? Evidence from thirty-nine sub-Saharan African countries”

[32] Qin Xiang Ng et al., “Yemen’s cholera epidemic is a one health issue,” Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 53, no. 4 (2020): 289.

[33] Ejiohuo et al., “Nourishing the Mind: How Food Security Influences Mental Wellbeing”.

[34] Ejiohuo et al., “Nourishing the Mind: How Food Security Influences Mental Wellbeing”

[35] Claire Klobucista et al., “Al-Shabaab,” Council on Foreign Relations 6, 2022.

[36] Tanja Schwarz et al., “Barriers to accessing health care for people with chronic conditions: a qualitative interview study”

[37] Elizabeth A Dowler and Deirdre O’connor, “Rights-based approaches to addressing food poverty and food insecurity in Ireland and UK,” Social Science & Medicine 74, no. 1 (2012): 44-51.

[38] Yasir Khan and Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, “Nutritional deficiencies in the developing world: current status and opportunities for intervention,” Pediatric Clinics 57, no. 6 (2010): 1409-1441.

[39] Mireya Vilar-Compte et al., “How do context variables affect food insecurity in Mexico? Implications for policy and governance,” Public Health Nutrition 23, no. 13 (2020): 2445-2452.

[40] Sophie Gepp et al., “Impact of unseasonable flooding on women's food security and mental health in rural Sylhet, Bangladesh: a longitudinal observational study,” The Lancet Planetary Health 6 (2022): S14.

[41] Margaret Lombe et al., “Cumulative risk and resilience: The roles of comorbid maternal mental health conditions and community cohesion in influencing food security in low-income households,” Social Work in Mental Health 16, no. 1 (2018): 74-92.

[42] Calgary Food Bank, “Mental Health”

[43] Seema Puri et al., “Nutrition and Cognitive Health: A Life Course Approach,” Frontiers in

Public Health 11, 2023:1023907.

[44] William Hermann Arrey, “Persistent Chronic Food Insecurity and Mitigation Challenges in Sahelian Africa: Can Lessons from ‘Targeted’ Social Protection Policies in the Horn of Africa be of help?”

[45] Felix Baquedano et al., “Food security implications for low‐and middle‐income countries under agricultural input reduction: The case of the European Union's farm to fork and biodiversity strategies,” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 44, no. 4 (2022): 1942-1954.

[46] Rambod Abiri et al., “Application of digital technologies for ensuring agricultural productivity,” Heliyon 9, no. 12 (2023): e22601.

[47] Rashmi Pandhare et al., “Modern Public Distribution System for Digital India,” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) Volume 3, 2016.

[48] Erica Dorr et al., “Life Cycle Assessment of Eight Urban Farms and Community Gardens in France and California,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 192 (2023): 106921, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.106921.

[49] Anna Gregis et al., “Community Garden initiatives addressing health and well-being outcomes: a systematic review of infodemiology aspects, outcomes, and target populations,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4 (2021): 1943.

[50] John S Mackenzie and Martyn Jeggo, “The one health approach—why is it so important?,” Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 4, no. 2 (2019): 88.

[51] Carla Oliveira et al., “Effectiveness of mobile app-based psychological interventions for college students: a systematic review of the literature,” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 647606.

[52] Courtney Barnes et al., “Improving implementation of school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs: a systematic review,” Translational Behavioral Medicine 11, no. 7 (2021): 1365-1410.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV