The OBB Framework in Achieving MHH Outcomes

It is more important now than ever before that governments act on the gender commitments[a] made as part of the Delhi Declaration,[1] especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a disproportionate impact on women and girls.[2] The efforts of multiple actors, including the union and state governments in India,[b] have led to a 20-percent increase in the use of hygienic protection methods[c] during menstruation among women aged 15-24 years, from 58 percent in 2015-16 to 78 percent in 2019-21.[3],[4] During the same period, the use of sanitary napkins for the same group increased from 42 percent to 64 percent.[5],[6] However, women with no schooling (44 percent), those from rural areas (73 percent), and those from the poorest households (54 percent) are found less likely to use a hygienic method of protection during menstruation compared to women with 12 or more years of schooling (90 percent), from urban areas (90 percent) and the wealthiest households (95 percent).[7] Thus, targeted efforts are required to improve the access and affordability of safe and hygienic menstrual products, to raise awareness regarding healthy menstrual practices, and to shape the attitudes of boys and men around menstruation.

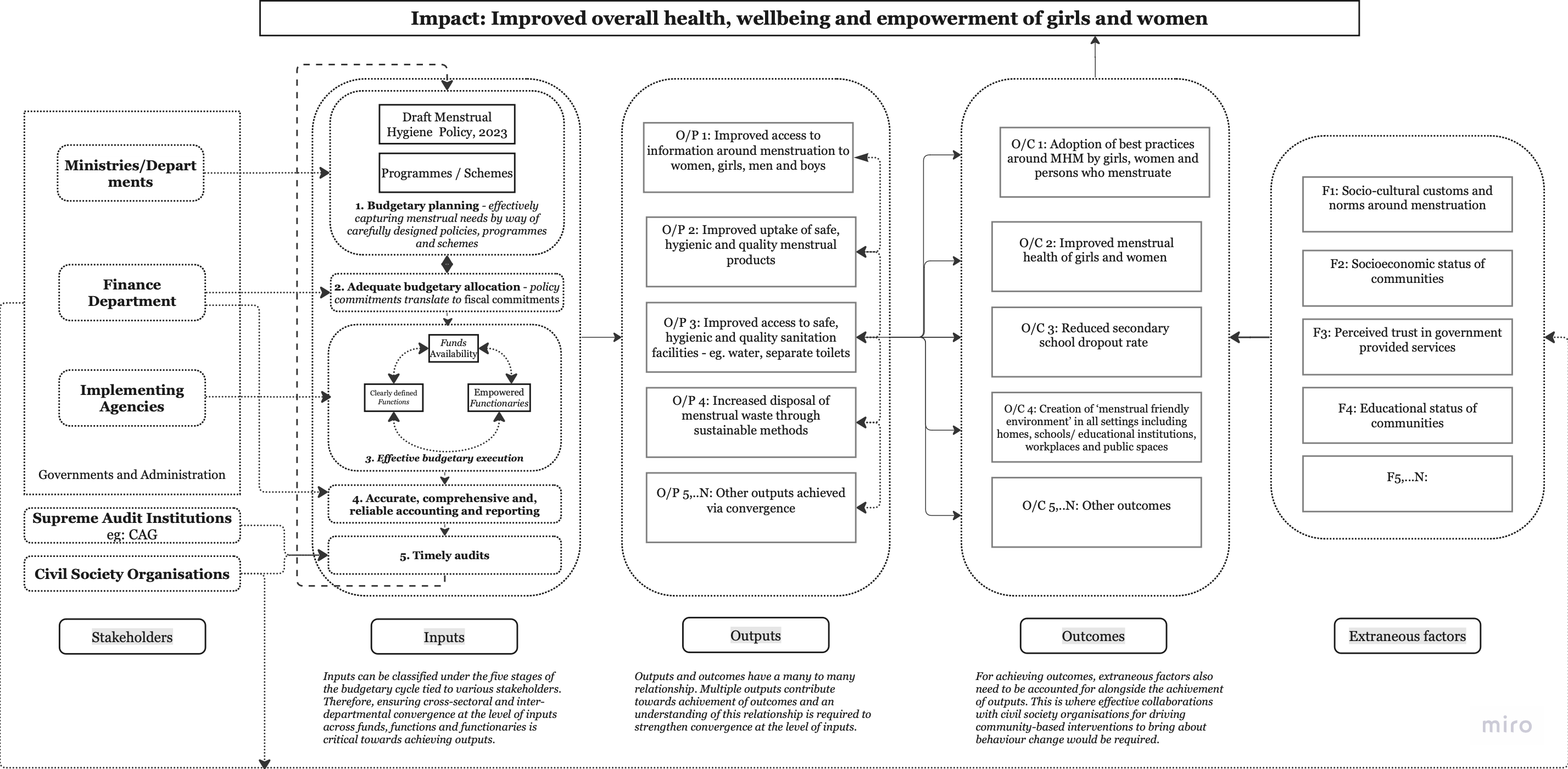

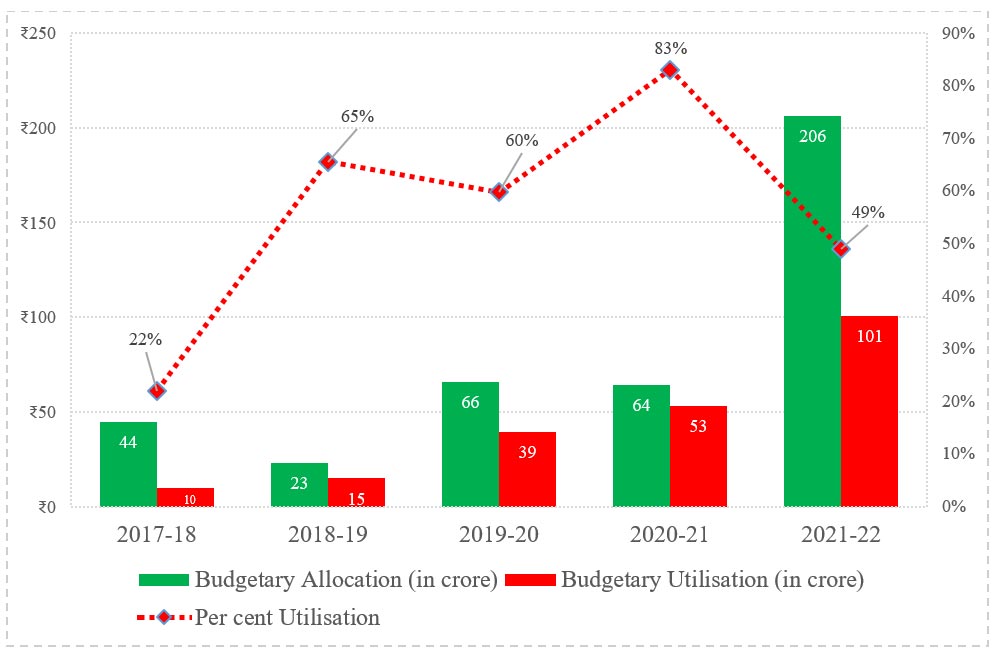

Given the multifaceted nature of challenges in the MHH area, the proposed OBB framework is particularly relevant because it links policy outputs derived from policy objectives to both fiscal and non-fiscal inputs across the budgetary cycle and considers extraneous factors in realising the desired MHH outcomes[8] (Figure 1). The OBB framework is based on the performance-based budgeting approach that has been adopted by governments worldwide, including the Government of India in 2005-06, to improve the efficiency of government spending.[9] It uses the central Public Financial Management (PFM)[d] tenets of allocative and technical efficiency[e] to help governments maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of spending towards achieving the desired impact—in this case, that of improved overall health, well-being, and empowerment of girls and women.

Figure 1: The Outcomes-Based Budgeting Framework

Source: Author’s own

Maximising the Efficiency of Spending

-

Prioritising MHH in budgets and identifying localised needs-based avenues for investment

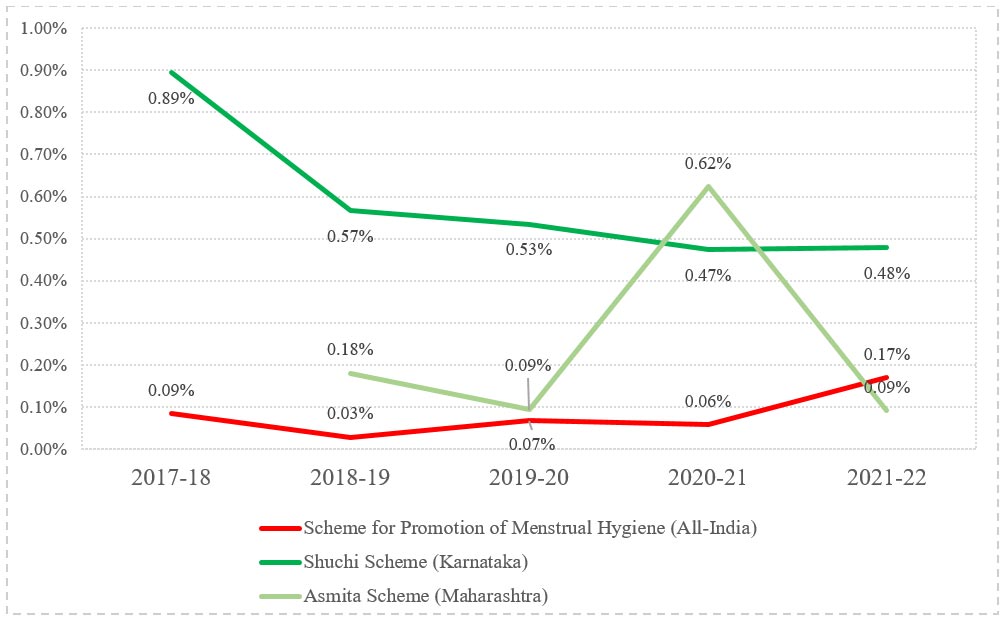

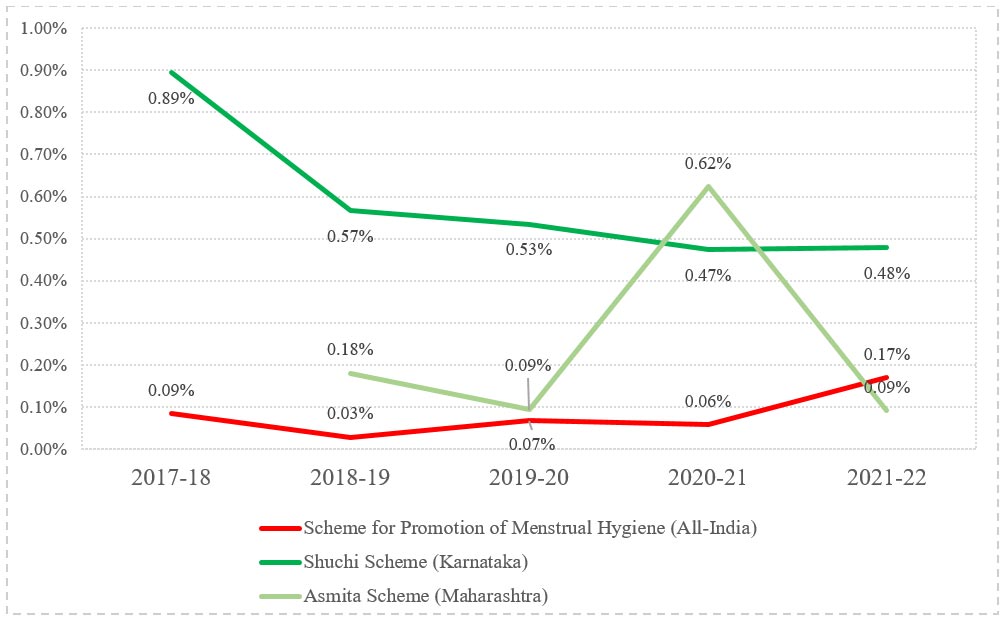

The three MHH schemes analysed—the Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene (Government of India), Shuchi Yojana (Government of Karnataka), and Asmita Yojana (Government of Maharashtra)—constitute less than 1 percent of the Department of Health’s total budget. Their budgetary shares have also fluctuated over five years (Figure 2). This merits careful consideration regarding the sufficiency and stability of budgetary allocations[f] towards ensuring timely, high-quality, and sustained service delivery in supplying menstruation products and sanitation facilities towards attaining the menstrual health outcomes as envisioned in the draft National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, 2023.[10]

Figure 2: Share of Budgetary Allocation Towards Menstrual Hygiene Schemes in Total Health Budgets

Source: Lok Sabha and the Detailed Demand for Grants[11],[12],[13]

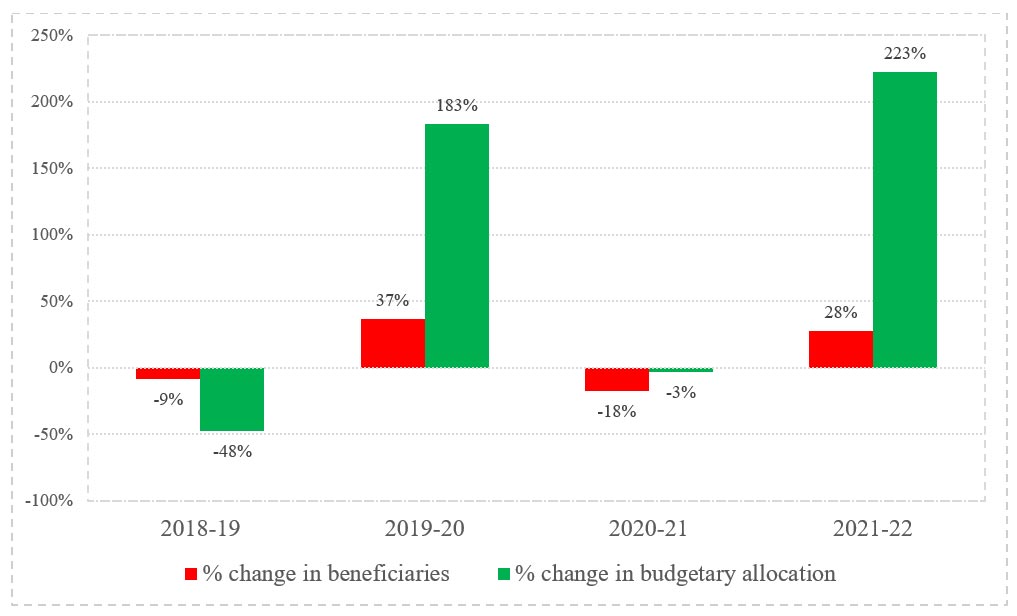

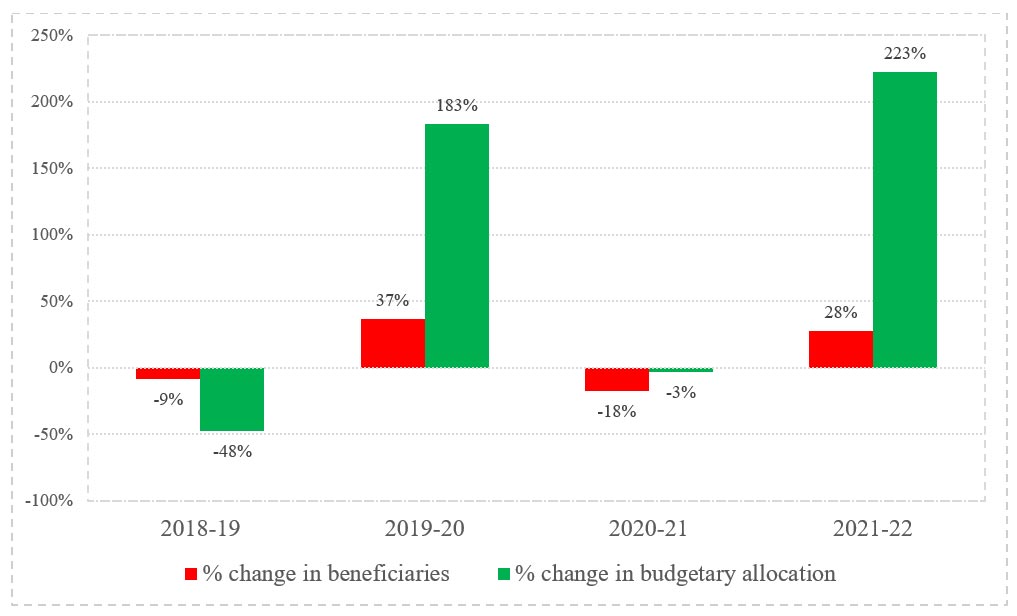

Moreover, the change in the budgetary allocation under the Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene is not proportional to the change in the number of adolescents who availed of the scheme benefits, indicating potential challenges in budgetary estimation and planning at the level of state governments (Figure 3). Thus, along with prioritising MHH in overall budgets, dedicated efforts are required within line departments to accurately plan and estimate programme- and scheme-specific budgets to align them with policy outputs and outcomes. For instance, the Departments of Women and Child Development, Health, Water and Sanitation, School Education, and Rural Development and Panchayat Raj could collaborate to ensure gender-disaggregated data availability, use, and sharing in standardised formats[g] to aid data-driven decision-making. Similarly, the technical capacity of personnel involved in the budgetary estimation would need to be improved.

Figure 3: Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene: % Change in Budgetary Allocation and Scheme Beneficiaries

Source: Lok Sabha[14]

Alongside increased budgetary allocation, state governments must identify localised needs-based avenues for investments, given that healthcare in India is a state subject and that there is a marked inter-state variation[h] in customs and practices around menstruation. A localised action plan must be developed and aligned with the national action plan, as proposed in the draft policy, including baseline assessments and a social and behaviour change principles-based information, education, and communication (IEC) strategy delivered in local languages.

-

Efficient utilisation of funds allocated towards MHH programmes and schemes

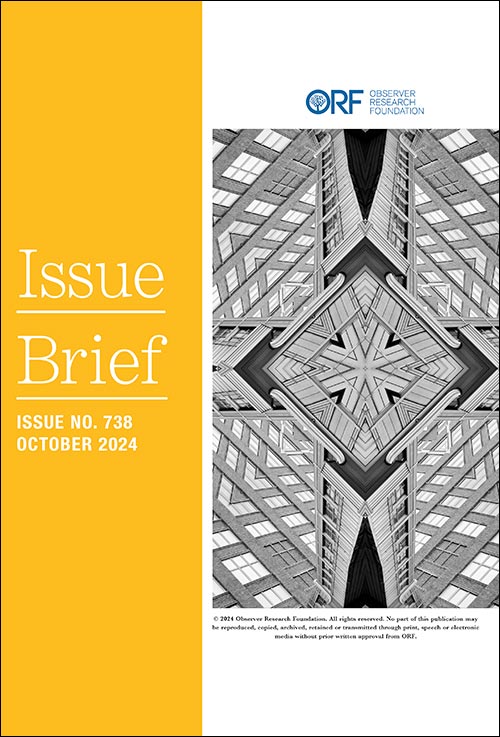

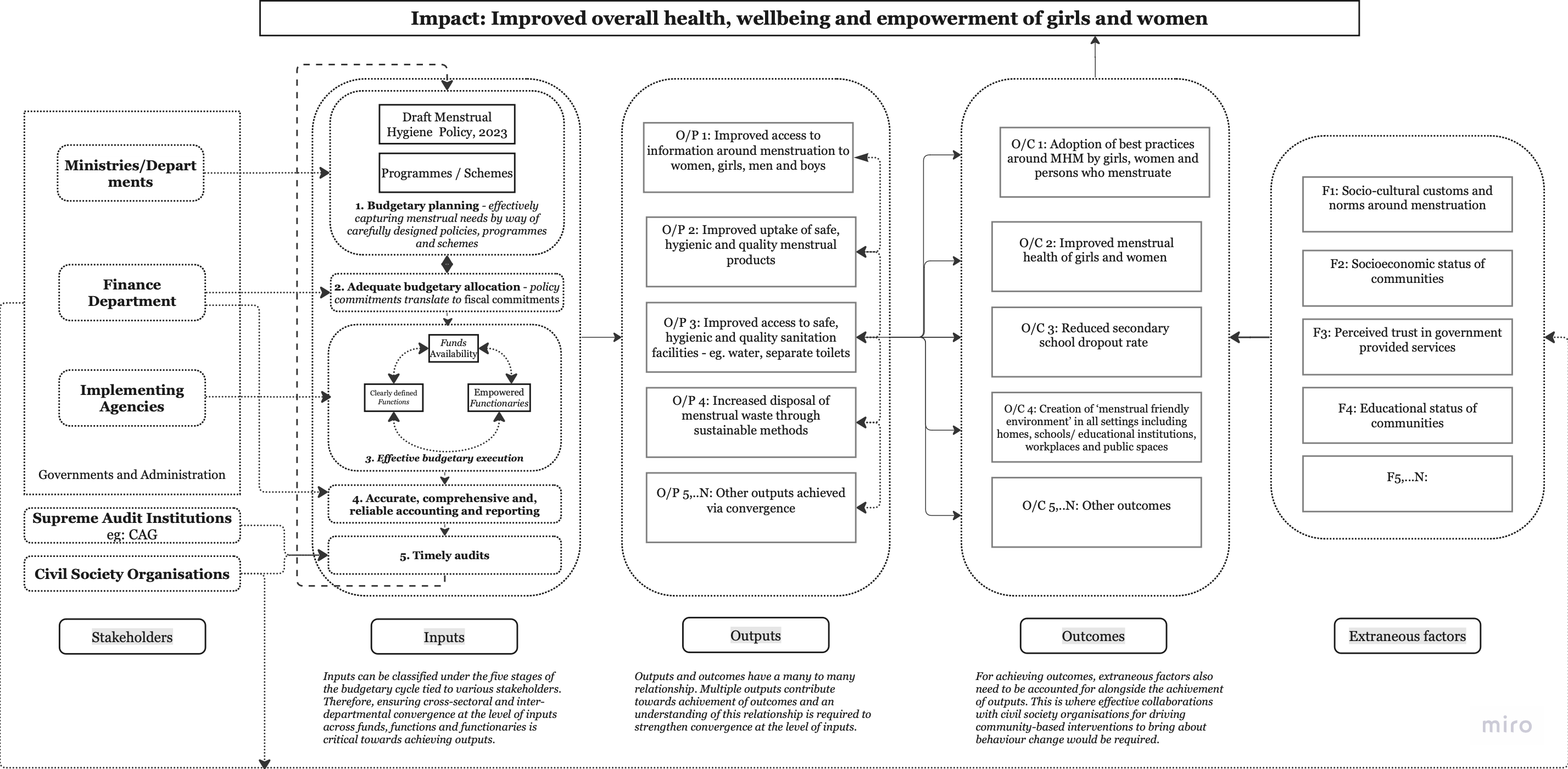

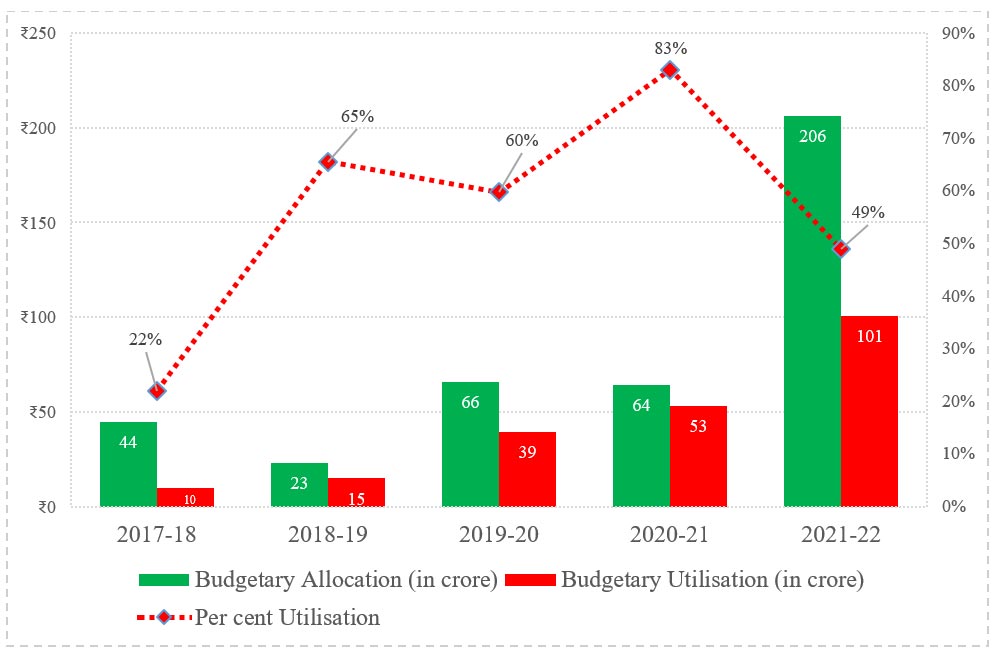

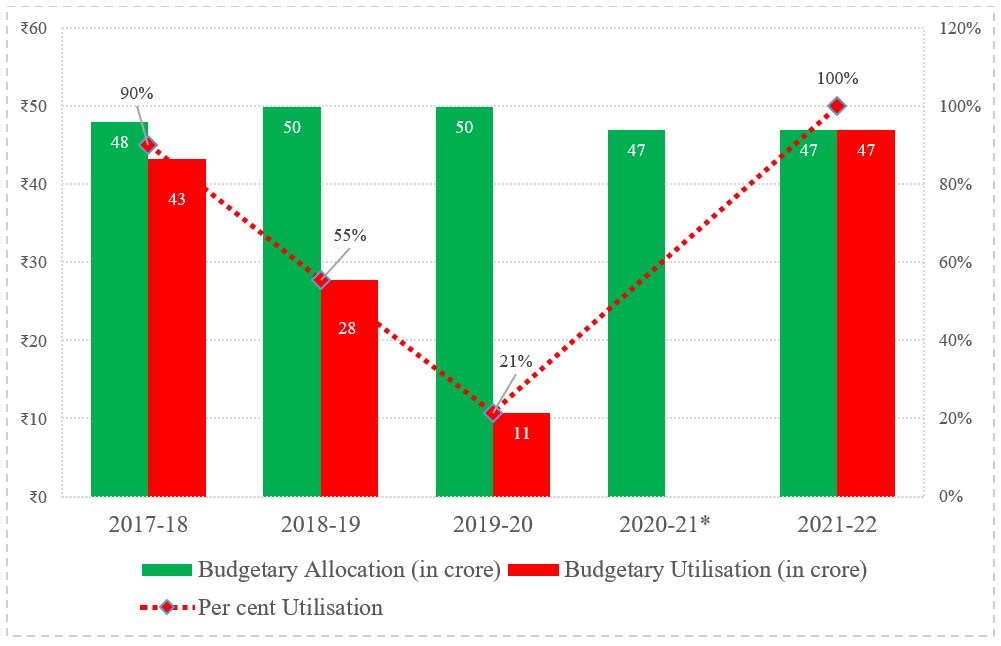

Union and state governments allocate less than 1 percent of the health budget to MHH schemes. The sub-optimal utilisation of allocated funds compounds this problem. In FY 2017-18, less than one-fourth of the allocated funds were spent on the Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene. Despite improvement in the utilisation of funds in subsequent years, the utilisation percentage dropped to 49 percent in FY 2021-22 (Figure 4). The Shuchi scheme of the Karnataka government saw a steep decline in utilisation of funds, from close to 100 percent in FY 2017-18 to 21 percent in 2019-20, followed by an increase to 100 percent in FY 2021-22, which raises concerns about scheme implementation (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Budgetary Allocation vs. Utilisation of Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene

Source: Lok Sabha[15] and Rajya Sabha[16]

Figure 5: Budgetary Allocation vs. Utilisation for the Shuchi Scheme

Source: Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Karnataka[i],[17]

Typically, sub-optimal utilisation of funds is the result of multiple factors such as incremental budgeting, lack of absorptive capacity, and technical capacity constraints at the level of implementing agencies, delayed fund releases, and challenges in procurements. Moreover, empowered functionaries with clearly assigned roles and responsibilities are essential to ensure the optimal utilisation of available funds towards achieving desired policy outputs. For example, frontliners such as ASHAs, Anganwadi workers, and school teachers responsible for spreading awareness regarding MHH or the distribution of sanitary products must be adequately trained, assigned specific responsibilities, and appropriately compensated for effective service delivery.

-

Sound accounting and reporting for improved transparency of budgets and data-driven decision-making

Most ongoing efforts of the union government to improve MHH are not dedicated schemes but components under umbrella schemes and programmes. The allocation and utilisation data of such scheme/s and their sub-components are typically not reported separately in the budgets, thus limiting effective oversight. For instance, since the Scheme for the Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene under the National Health Mission is implemented through State Programme Implementation Plans (PIPs), its budgetary allocation and utilisation cannot be traced in the health ministry’s Detailed Demand for Grants (DDGs). Similarly, the actual budgetary utilisation for Maharashtra’s Asmita scheme was not reported in the state DDGs between FY 2019-20 and FY 2021-22.[18] Therefore, alongside prioritising MHH scheme/s in budgets and strengthening their execution, there is a need for accurate, comprehensive, and reliable accounting and reporting of fiscal data for improved budget transparency. Additionally, the availability and use of outputs and outcomes-focused data for effective monitoring and budgetary planning would aid in achieving the objectives outlined in the draft policy.

-

Timely performance audits for effective oversight

While CAG performance audit reports[j] for flagship MHH scheme/s and initiatives could not be found, independent findings have flagged gaps in implementation. In Maharashtra, for instance, complaints of discomfort with the sanitary napkins supplied under the Asmita scheme were reported by women and girls, leading to poor scheme uptake.[19] However, the state government incorporated the feedback to revise the specifications concerning napkin size and soaking capacity during procurement.[20] This illustrates the importance of timely audits as a critical link between the implementation and reporting stages of the budgetary cycle and the planning and allocation stages to nudge action on behalf of governments and foster citizens’ trust in government services. Collaborations with civil society can further strengthen these efforts.

Maximising the Effectiveness of Spending

The spending on MHH would be effective if it leads to desired outcomes and impact over time. Outcomes share a one-to-many relationship with outputs—that is, attaining one outcome is mainly related to realising multiple outputs. For instance, increased awareness amongst adolescents, coupled with access to affordable, safe products and hygienic sanitation facilities would be essential in realising the outcome of improved MHH or higher school attendance for adolescents. Interdepartmental coordination across policy inputs is critical to the realisation of multiple outputs (Figure 1).

Outcomes also depend on extraneous factors such as socio-cultural norms, levels of education, socio-economic status of communities, and perceived trust in government services (Figure 1). Therefore, trust-based collaborations among governments and non-profit and for-profit organisations to drive community-based interventions would nudge positive social and behavioural change. For instance, partnering with start-ups and businesses to procure sustainable sanitary waste disposal products and services for government schools and institutions could change sanitary waste disposal behaviours while aiding in the achievement of disposal-related outcomes.

The Way Forward

As governments continue to strengthen their commitment towards addressing MHH challenges,[21] increased efforts are required across the budgetary lifecycle to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of spending to realise value for taxpayers’ money. The draft policy by the union government is a step in the right direction towards realising MHH outcomes. However, as suggested by the OBB framework, both the union and the state governments must do the following:

- Ensure adequate budgetary allocation towards MHH and cater to localised needs to realise the draft policy’s outcomes.

- Ensure efficient fund utilisation through timely fund releases, empower functionaries with clearly assigned functions, foster inter-departmental coordination, and collaborate with civil society organisations and communities.

- Facilitate accurate, comprehensive, and reliable accounting and reporting of fiscal and non-fiscal data to aid data-driven decision-making.

- Undertake timely audits to provide critical feedback during budgetary planning and allocation.

Adopting such a framework towards designing and implementing gender-responsive policies would be essential to achieving the overall health and well-being of girls and women and realising the women-led development agenda.

This brief was first published in ORF’s Hope in the Horizon: India’s Youth and Global Futures, which can be accessed here: Hope in the Horizon: India’s Youth and Global Futures (Vol. 1) (orfonline.org)

Priyanka Parle is an independent public finance consultant and a former Chief Minister’s Fellow in Maharashtra.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or views of the affiliated institution.

Endnotes

[a] The states committed to greater economic and social empowerment of women alongside enhanced food security, nutrition, and overall well-being.

[b] Maharashtra’s ‘Asmita Yojana’, Rajasthan’s ‘Udaan’, Andhra Pradesh’s ‘Swechcha’, Kerala’s ‘She Pad’, Odisha’s ‘Khusi’, Chhattisgarh’s ‘Suchita’, and Sikkim’s ‘Bahini’.

[c] Hygienic methods of protection are defined as locally prepared napkins, sanitary napkins, tampons, and menstrual cups, as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21.

[d] According to the International Monetary Fund, PFM can be defined in terms of laws, institutions, systems, and processes essential for governments to implement fiscal policy. The PFM lens is linked to how governments raise public resources and manage these resources to ensure public service delivery.

[e] Allocation of sufficient funds by states to areas of strategic priority (allocative efficiency) and utilisation of these resources efficiently to derive the maximum value for money spent (technical efficiency), together with ensuring sustainability in spending (fiscal discipline), are key to sound PFM.

[f] Typically, fiscal policy constraints, lower capacity to raise own revenues or fluctuating revenues, increasing committed expenditures, and/or unforeseen contingencies constrain sufficient funds allocation by governments. Similarly, as highlighted in consecutive Finance Commission reports, vertical fiscal imbalance constrains greater fiscal commitment from state governments towards social sector responsibilities.

[g] Both financial (for instance, need for scheme funds disaggregated by sub-schemes and components or projects thereof) and non-financial (for instance, number of beneficiaries disaggregated by age group, educational background, and caste group).

[h] Bihar (59 percent), Madhya Pradesh (61 percent), and Meghalaya (65 percent) have the lowest percentage of women using hygienic methods of menstrual protection, below the national average of 78 percent.

[i] Actuals for FY 2020-21 were not reported for Shuchi scheme in the budget/detailed demand for grants.

[j] The performance audits conducted by the CAG examine whether schemes/programmes are being implemented efficiently and effectively by concerned agencies and whether taxpayers have received value for money. These help in constructively promoting economical, effective, and efficient governance.

[1] The Group of Twenty (G20), G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration, September 2023, New Delhi, The Group of Twenty (G20), 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/CPV/G20-New-Delhi-Leaders-Declaration.pdf

[2] UN Women, “Your Questions Answered: Women and COVID-19 in India,” https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2021/7/faq-women-and-covid-19-in-india

[3] International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India, Mumbai, IIPS, 2017, https://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf

[4] International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: Volume 1, Mumbai, IIPS, 2021, https://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

[5] “National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India”

[6] “National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: Volume 1”

[7] “National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: Volume 1”

[8] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-Based Management, Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2022, https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/EV(2022)2/en/pdf

[9] K Gayithri, Performance-Based Budgeting: Subnational Initiatives in India and China, Bangalore, The Institute for Social and Economic Change, 2015, http://203.200.22.244/WP%20334%20-%20K%20Gayithri-Final.pdf

[10] India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Draft National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, New Delhi, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2023, https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Draft%20Menstrual%20Hygiene%20Policy%202023%20-For%20Comments.pdf

[11] Lok Sabha unstarred question no. 2986, Thomas Chazhikadan, https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1711/AU2986.pdf?source=pqals; Lok Sabha, “Questions & Answers,” https://sansad.in/ls/questions/questions-and-answers.

[12] “Detailed Budget Estimates of Expenditure-Demand-Wise for the Year 2018-19,” Karnataka Budget Documents, https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/11-VOLUME-02%20FULL-%20EXP2018-19.pdf; Karnataka Budget Documents. https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/english.

[13] “Demand No. L-2,” Rural Development Department, Maharashtra Budget Books, https://beams.mahakosh.gov.in/Beams5/BudgetMVC/MISRPT/MistBudgetBooksNew.jsp?year=2019-2020#; Maharashtra Budget Books, https://beams.mahakosh.gov.in/Beams5/BudgetMVC/MISRPT/MistBudgetBooksNew.jsp?year=2019-2020

[14] Lok Sabha unstarred question no. 2986, Thomas Chazhikadan, https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1711/AU2986.pdf?source=pqals; Lok Sabha, “Questions & Answers,” https://sansad.in/ls/questions/questions-and-answers.

[15] Lok Sabha unstarred question no. 4132, P.P. Chaudhary, Arjun Lal Meena, Kaushal Kishore, Jayant Sinha, https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/175/AU4132.pdf?source=pqals; Lok Sabha, “Questions & Answers,” https://sansad.in/ls/questions/questions-and-answers.

[16] Rajya Sabha unstarred question no. 2336, Binoy Viswam; Rajya Sabha, “Questions & Answers,” https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers.

[17] “Detailed Budget Estimates of Expenditure-Demand-Wise for the Year 2018-19”

[18] “Demand No. L-2”

[19] Tabassum Barnagarwala, “Asmita Scheme: After Complaints of Poor Quality, Officials Try Sanitary Napkins Before Rolling them out for Schoolgirls,” The Indian Express, March 5, 2019, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/asmita-scheme-after-complaints-of-poor-quality-officials-try-sanitary-napkins-before-rolling-them-out-for-schoolgirls-5611023/

[20] Barnagarwala, “Asmita Scheme”

[21] Abhinay Deshpande, “Maharashtra May Further Subsidise Sanitary Napkins for School Girls, Self-Help Groups,” The Hindu, March 10, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/maharashtra-may-further-subsidise-sanitary-napkins-for-school-girls-self-help-groups/article66603839.ece

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV