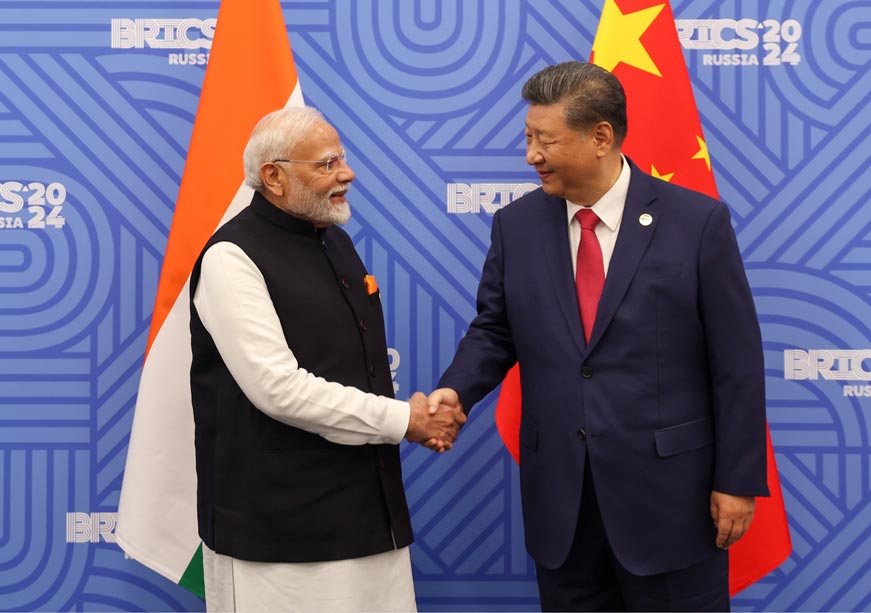

This week has been one of the most eventful in recent times in the chronicles of Indian diplomacy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping signalled their intent to defuse tensions with their meeting on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Russia. This development has been preceded by South Block announcing that both sides had agreed to patrolling arrangements along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). This indicates an initiative to resolve the tense military stand-off that went on for more than four years after Beijing unilaterally tried to change the status quo along the LAC in 2020 that led to the deaths of both Indian and Chinese soldiers. While this has been met with a rapturous response, particularly in the Indian media, Chinese mandarins have issued a terse reply that having “reached a solution” they would work with Delhi to “implement the plan effectively”.

The LAC crisis has also underscored the larger problem that both nations must resolve the issue of the undemarcated border permanently.

India’s security establishment has also been guarded in its assessment. Army chief General Upendra Dwivedi has underscored the need for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to withdraw to its April 2020 positions, then for China to also address the issue of militarisation of the border in violation of the pacts it signed. The LAC crisis has also underscored the larger problem that both nations must resolve the issue of the undemarcated border permanently. In this context the move to revive the mechanism of Special Representatives — National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi — on the boundary question is a positive development. It is only by meeting these conditions that China can build trust in this relationship. Moreover, with the current thinking with respect to China being “verify” before you “trust”, it will take some time to get an accurate picture of ground zero of the India-China contestation. It is said that all’s well that ends well. But it will be unwise for us to dismiss this episode, and not heed the lessons learnt from it. First, we do not know the reasons that provoked China to unilaterally change the status quo along the LAC. Equally, we may not comprehend the motivation for this climbdown by Beijing.

However, there are some pressures developing for the Chinese system. In 2020, China seemed to be at the apogee of its power having contained the Covid-19 pandemic in Wuhan, it then contrasted it with many parts of the world grappling with the contagion. This bolstered the rhetoric regarding Chinese triumphalism that could have provoked Beijing belligerence along the LAC. In 2024, China is still reeling from the economic shock induced by its own recipe to deal with the virus. Economic indicators on quarterly GDP growth point to the fact that China may not be in a position to meet its own target. Besides, there are other consequences of a slumping economy like a battered real estate sector that contributes to a quarter of the GDP and high unemployment. For China too, the centre of gravity is shifting. In the assessment of its own strategists, Beijing sees “independence-minded elements” personified in the likeness of Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te getting stronger. In his first National Day address recently, Lai asserted Taiwan’s “independence”, stating that Beijing had no right to represent Taipei. This has implications for Xi’s aggressive expansionism that seeks to reunify Taiwan, if necessary, by military force.

Economic indicators on quarterly GDP growth point to the fact that China may not be in a position to meet its own target.

Almost on cue, China ordered joint military drills to “punish” Lai. This is the second time this year that China has launched war games around the Taiwan straits.

There is also a pushback emerging elsewhere with the Philippines putting up a fight against China’s claims in the South China Sea. To compound matters, the newly appointed Japanese PM Shigeru Ishiba has proposed an “Asian Nato” on the lines of the transatlantic defence mechanism. For Beijing, which has railed against Washington’s “bloc politics”, Ishiba’s new security plan raises the spectre of nations of its periphery aligning closely with the US and its allies in the region. These developments may have created some incentives for Beijing to try and mend fences with India along the LAC.

The optics of the Modi-Xi summit, and India taking centre stage at the BRICS summit — which is perceived in the Anglosphere as an “anti-West” forum — has caused significant heartburn in some quarters. Alternatively, for India, BRICS remains a non-West platform as reiterated by PM Modi at the Russia summit that the organisation must not foster a notion that it seeks to replace international institutions. The West pays lip service to reforming global institutions, yet in practice it seeks to maintain the same post-war dominance despite the geopolitical rise of the East and new emerging powers. India straddles the West-led Quad and BRICS groupings with equal finesse, underlining that a rising Bharat will not foreclose its partners, unlike in the past, and will let its national interests guide the trajectory of its external engagement. Engaging with platforms like BRICS allows India to amplify its own voice as well as the concerns of the Global South. This is not to say that BRICS doesn’t have international contradictions. For New Delhi, managing ties with Beijing within the BRICS is an important priority. Working with Russia on the one hand and with nations like Brazil and South Africa on the other allows it to work with China on an equal footing, while continuing to highlight the concerns of the developing world. The Kazan summit has shown that can also provide new opportunities for bilateral engagements. If the Xiamen summit of BRICS in 2017 had managed to untangle the knot of Doklam, the Kazan summit has allowed for a semblance of normalcy to return in Sino-Indian relations after Galwan.

It can only be hoped that the two nations won’t need another BRICS summit in the future to further reconfigure their ties.

This commentary originally appeared in Financial Express

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV