-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Archishman Goswami, “An India-Armenia Intelligence Partnership for the 2020s,” Issue Brief No. 741, October 2024, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The growing potential of the India-Armenia bilateral is anchored in defence and security cooperation. As a central component of the latter, intelligence liaison can enable policymakers to accomplish the full potential of this bilateral.

Espionage has a long history in both India and Armenia. Kautilya’s Arthashastra formalised the politics of intelligence within the statecraft of Mauryan India.[1] A millennium later, the Byzantines recruited heavily from their Armenian frontier provinces for the empire’s tasinarioi[a] units.[2] Geopolitical volatility, including in the Caucasus, adds relevance to these legacies. As a consequence of the war in Ukraine, the regional influence of Russia—which has been the traditional security guarantor of the South Caucasus—has dwindled. In the subsequent multi-stakeholder contest for control in regional geopolitics, Armenia has sought to redefine its strategic posture away from its post-Soviet identity. This shift has reiterated the need for increased diversity of strategic partners for Yerevan. India occupies a position of trust in Armenia’s strategic community. Defence relations have strengthened since 2020 as a result of India’s diplomatic and military support for Armenia in its war of self-defence against Azerbaijan. In this context, close security ties with India, especially in intelligence, gain significance.

This brief conceptualises a roadmap for India-Armenia intelligence relations in a changing world order. Given the proclivity of Indian foreign policy towards ‘geometric diplomacy’[b] as well as the relative novelty of India-Armenia ties, issue-based intelligence-sharing between partner agencies in New Delhi and Yerevan would achieve two key common goals. First, it could add greater weight to the bilateral relations. Second, it will allow policymakers in both countries to identify areas of convergence, opportunities, and threats within the partnership in the short and long term. In this context, this brief examines relevant internal developments in Armenia that incentivise cooperation with India.

Domestic Drivers

It was in late 2022 that the Armenian government began restructuring and reforming its intelligence community, with particular focus on the National Security Service (NSS), its primary intelligence agency since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. These changes are driven both by a desire to ensure greater intelligence oversight and to push back against perceived Russian subversion of its security apparatus. The changes suggest increased potential for closer Indo-Armenian intelligence cooperation.

The first of these reforms is the restructured mandate of the NSS. Despite the abovementioned changes, the NSS remains one of the most important intelligence agencies in Armenia’s national security structure, with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan reiterating that the reforms do not “violate the status quo in any way”.[3] Yet, strategic considerations have compelled the agency to work more closely and share more information with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which has also been given key intelligence mandates within domestic security.[4] Additionally, oversight mechanisms have been developed as a counterintelligence measure, with the dissolution of the NSS’s internal Investigative Department in January 2024 and the transfer of its functions to the Investigative Department of the multi-agency National Security Council (NSC) to strengthen security measures within the service.[5]

Arguably, the most significant change has been the formation of the Foreign Intelligence Service (FIS) in 2022. The FIS has been mandated with foreign intelligence activity under centralised oversight and the direction of Kristinne Grigoryan, former Human Rights Defender.[6],[7] The establishment of the FIS serves two key strategic purposes. First, it demonstrates PM Pashinyan’s desire “to transform and develop our capabilities according to modern conditions and requirements.”[8] Second, it signals a growing understanding of the centrality of intelligence in Armenia’s new, outward-facing foreign policy. Intelligence in post-Soviet Armenia historically served domestic functions. The institutionalisation of the FIS presents a shift in Armenian strategic thinking, which is increasingly recognising the value of intelligence in achieving foreign security policy goals.

The establishment of the FIS reflects Armenia’s desire to diversify its strategic partnerships amid a shifting regional order. The formation of a new foreign intelligence service free of historical and cultural baggage was driven by disappointment at Russia’s failure to secure Armenian territory in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and concerns over Moscow’s entrenched intelligence culture and agents.[9],[10] Additionally, countries seeking to replace Russia’s receding influence in the Caucasus reinforced the need for Armenia to gain a better understanding of these countries’ intentions and establish reliable partnerships with more diverse strategic partners.[11]

As a key ally to Armenia in the defence space, India is well positioned to equip and liaise with the FIS. In specific policy terms, this may involve signing Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) for intelligence sharing with the FIS. These may bear structural resemblance to the intelligence-sharing agreement concluded in 2023 between India’s external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) and its counterpart in Saudi Arabia, the Presidency of State Security (PSS), which emphasised mutual exchanges and training of personnel from the agencies.[12]

Additionally, the Indian intelligence services could have a first-mover advantage to fill a critical gap in Armenia’s security architecture and gain future returns. Increased summit meetings between the prime ministers of both countries might contribute to intelligence diplomacy, particularly given the centralisation of intelligence within both countries’ security architectures and the overhaul of Armenia’s security bureaucracy. Likewise, mechanisms of information sharing both at the bilateral and multilateral levels would be commensurate with the current trajectory of Armenia’s intelligence systems and India’s efforts to expand its presence further afield. Meetings between the chiefs of Armenia’s NSS and India’s Intelligence Bureau (IB), or between the FIS and R&AW, would enable both sides to gain a better understanding of how these reforms will shape security relations between the two countries and how they can work together more efficiently on converging areas of interest.

The reforms in Armenia’s intelligence community also increase the scope for India to strengthen its position as an intelligence partner to Armenia. Although these reforms indicate a shift away from Russian influence on Armenia’s intelligence community, geostrategic circumstances necessitate the preservation of some backchannels between Armenian and Russian intelligence services. Closer intelligence cooperation with India would allow Armenia to pursue reforms to its domestic intelligence community, even as Indian intelligence services such as the R&AW use their good offices with Russian counterparts to serve as backchannel interlocutors with the FIS and NSS.

Emerging technologies are a critical area of intelligence cooperation between India and Armenia. While bilateral collaboration in this sector is still minimal, a September 2023 MoU between India and Armenia “to promote closer cooperation and exchange of experiences and digital technologies-based solutions” indicates the untapped potential of cooperation and the political will of both New Delhi and Yerevan to coordinate closely in this domain.[13]

In recent years, Armenia has come to regard investment in research and development as vital to its national security strategy.[14] A rapidly growing economy, a thriving startup ecosystem, and the influx of Russian and Ukrainian entrepreneurs escaping the instability caused by the war have aided Armenia’s ambitions to become a technological powerhouse in the South Caucasus.[15]

These ambitions are reflected in Armenia’s ‘Transformation Strategy 2050’ which seeks, among others, to improve standard of living and expand the country’s global influence through the incentivisation of the domestic technology sector. Similar ambitions are reflected in India’s ‘Viksit Bharat 2047’ vision, characterised by the pursuit of “a knowledge-based economy”, “export-oriented manufacturing base”, and the growth of the country to become a global destination for industry.[16],[17] Both visions prioritise the development of a robust domestic technological sector. Therefore, it is critical to protect the sector from foreign interference and ensure its effectiveness for power projection.

In this context, technological cooperation between the two countries must grow to allow bilateral relations to achieve their full potential across important sectors. As an aspiring regional technological powerhouse, Armenia is looking to India for expertise, material resources, and manufacturing and design facilities in strategically important sectors, such as semiconductors and space technology. Similarly, Indian companies are looking to harness Armenia’s rapidly growing yet relatively untapped domestic technology market.[c]

Securing the development of emerging technologies and bilateral collaboration in this area is key, with intelligence cooperation being a crucial instrument in the collaboration. Technological innovation and trade secrets have long been targets for rival intelligence agencies. However, the scale of this problem has increased in recent years, with great-power dynamics and interstate strategic competition dominating the global security agenda.[18] In this context, it is vital that Indian and Armenian intelligence services expand cooperation at a bilateral level—which would allow for tighter control over the dissemination of classified information compared to multilateral platforms that include other states and intergovernmental actors—to secure their joint efforts in the technological space against the risk of being compromised.

Various templates of action exist to facilitate such cooperation. The early 2020s saw India organise NSA-level summit talks with key strategic partners to facilitate coordination on emerging technologies and their ramifications for intelligence and national security. The US-India Initiative on Critical Technology (iCET), established in 2023 and led by the National Security Advisors of both countries and attended by senior Indian and US intelligence officials, has set an organisational template that was emulated in the Technology Security Initiative (TSI) between the UK and India launched in July 2024.[19],[20] Similar NSA-level agreements may be explored between India and Armenia, both to share threat intelligence and strategic expertise on countering challenges within the framework of intelligence and to facilitate longer-term cooperation between the two countries in the field of emerging technologies.

Defence diplomacy may also be useful. Historically, militaries have acted as agents of secret diplomacy. For instance, in the 1980s, the British Military Liaison Mission (BRIXMIS) was tasked with the collection of secret intelligence during sanctioned visits to East Germany while establishing coordination with GDR officials as a countermeasure against miscalculation and misunderstanding between the Western and Eastern blocs in the final quarter of the Cold War.[21] India and Armenia have already deployed defence attachés for diplomatic missions in the other country. As the scope for intelligence cooperation in the emerging technology space grows, these officials may be tasked with coordination and information exchange on innovations of strategic value to both countries.[22]

Non-traditional security and intelligence bodies can also help provide adequate representation for the private sector spearheading innovation in emerging technologies in both countries. Liaison units comprising senior intelligence officials from both countries and representatives from the private sector would provide the necessary interface to help both countries expand their technological cooperation while allowing their intelligence services to draw on an existing pool of innovations from both countries.[d],[23]

External Factors

The drivers discussed in the previous section present opportunities for expanding intelligence cooperation between India and Armenia. This, however, can only be operationalised in the context of challenges common to both countries from the external security landscape. These include the growing formalisation of the Türkiye-Pakistan strategic axis and its ramifications for South Asia and the Caucasus, and transnational security challenges posed by organised criminal networks and drug flows stretching from the Golden Triangle in India’s neighbourhood to Europe via the South Caucasus.

The emergence of a Türkiye-Pakistan axis has coincided with burgeoning India-Armenia relations. The Ankara-Islamabad nexus, which is primarily a product of the past decade, is shaped by Pakistan’s antagonism towards India, and Türkiye’s for Armenia. Turkish hostility towards Armenia is multidimensional, manifesting most visibly in its military, economic, and diplomatic support for Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh war. Ankara’s support for Pakistani claims on Kashmir and Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan’s public statements about India’s domestic politics have eroded relations with New Delhi.[24] Similarly, alongside its decades-old hostility towards India, Pakistan has refused to even accord Armenia diplomatic recognition.[25] These hostilities have intensified, necessitating closer Indo-Armenian intelligence cooperation on this front.

Pakistan’s efforts to integrate with Türkiye’s growing footprint in the Caucasus has resulted in more direct provocation of Armenia. Despite Islamabad denying these claims, both PM Pashinyan and senior NSS officials have noted that Pakistani nationals were aiding the Azeri military in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.[26],[27] Türkiye and Pakistan are also developing the KAAN fighter jet programme, along with Azerbaijan.[28],[29]

Türkiye has also adopted a more confrontational stance against India, engaging in covert interference in the latter’s domestic affairs. While unverified, there have been reports of contractors from Turkish private military company SADAT being deployed to Jammu and Kashmir to support the Pakistan-backed insurgency in the state.[30] Indian intelligence agencies have also noted increased financial support from Türkiye for extremist organisations and front organisations in India, using Nepal as a conduit.[31]

Developments such as these highlight the need for closer intelligence liaison between India and Armenia on the Turkish-Pakistani axis and its impact on the trajectory of Indo-Armenian relations. A key element of this cooperation could be the movements and activities of Pakistani foreign fighters travelling to the Caucasus to combat Armenian forces. India has wide intelligence networks and capabilities in Pakistan and the broader Af-Pak regions, which are home to a variety of terrorist safe havens. Its foreign intelligence service, the R&AW, is thus well positioned to supply intelligence to its Armenian partners regarding Pakistani mercenary outfits conducting operations in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Yerevan should reciprocate through regular intelligence sharing on these fighters and their activities and pursuing joint interrogations and debriefing where possible. For India, intelligence that holds the greatest value would include Türkiye’s strategic posture in the region, the activities of Pakistani mercenaries in Nagorno-Karabakh, and their international linkages.

Another area of intelligence cooperation is on issues of regional connectivity, which are playing an increasing role in bilateral security relations. India has increasingly sought to diminish its economic and transit dependence on Türkiye and Turkish allies such as Azerbaijan in West Asia and the Caucasus by projecting Armenia as an alternative transit node in projects such as the International North-South Transport Corridor, which links India to European markets.[32] Such arrangements have brought economic benefits to both India and Armenia, with India leveraging its investments in Chabahar port in Iran to facilitate Armenian trade via shipping lanes.[33] It also undermines Türkiye’s ability to leverage its hegemony and geostrategic influence as a transit node in the region.

Against this backdrop, it is vital that Indian and Armenian intelligence officials liaise regularly on strategic challenges to their regional connectivity as a result of the Türkiye-Pakistan axis. These challenges may range from kinetic and cyber threats, to simpler counterintelligence challenges relating to the subornment of private or state contractors working on supply chain issues. Consistent and formalised procedures of liaison between the R&AW and the FIS would go a long way in countering some of these challenges.

Beyond liaising to counter hostile threat actors, non-traditional and transnational security challenges such as counternarcotics also underscore the need for greater cooperation between Indian and Armenian intelligence services. Shaped partly by geopolitical volatility and the subsequent entrenchment of organised crime in regional political dynamics, countering drug trafficking and the consequent economic power of organised crime groups will require Indian and Armenian intelligence communities to leverage their regional expertise, infrastructure, and assets to achieve solutions effectively.

Although drug trafficking and drug abuse have been less pronounced in Armenia compared to its neighbours in the Caucasus, Georgia and Azerbaijan, the country has experienced a surge in these issues in recent years, with drug-trafficking cases reportedly increasing from 420 to 743 between 2021 and 2022.[34] Criminal groups are increasingly using Armenian territory as a conduit for illicit trade between drug-producing countries in South and Central Asia to larger illicit markets in Europe.[35]

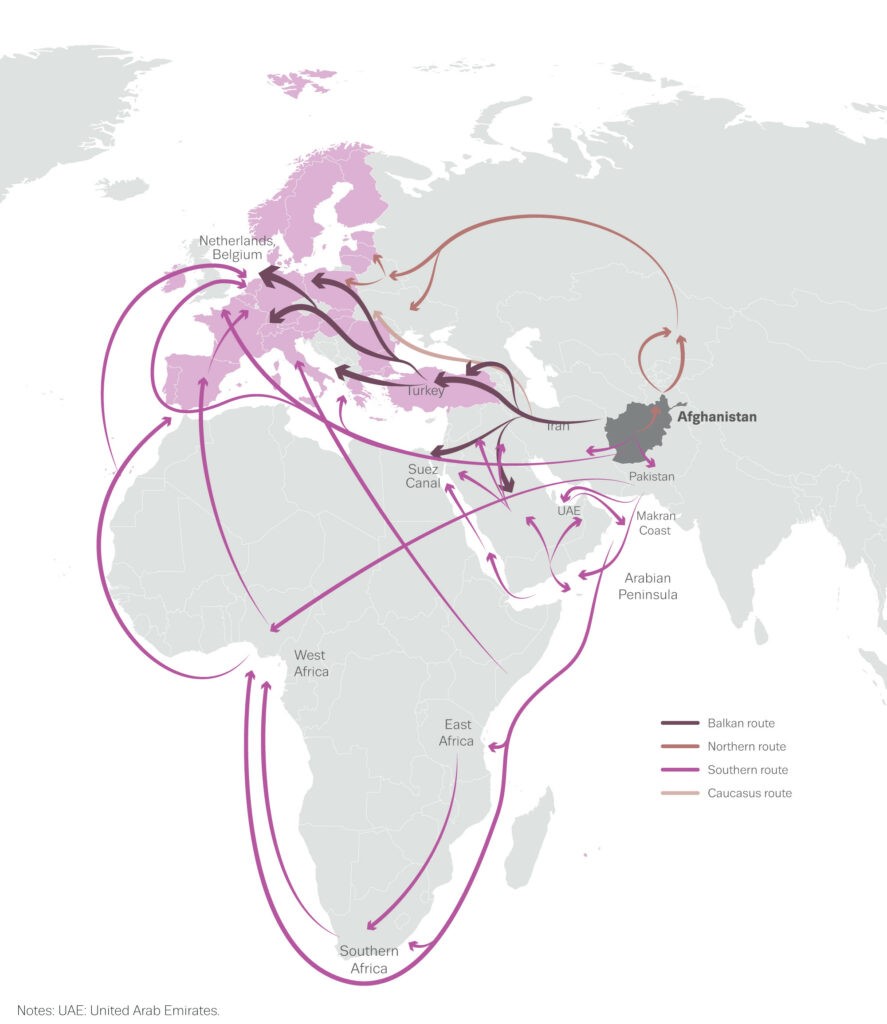

Figure 1: Known Heroin Trafficking Routes Between Afghanistan and Europe

Source: European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA)[36]

The drugs and raw materials that are smuggled to Europe via Armenia mainly include heroin and cocaine—an illicit trade historically monopolised by Iranian and Georgian cartels.[37] Figure 1 highlights Armenia’s geographic position within both the Northern and Caucasus heroin trafficking routes between Afghanistan, a key source for both processed heroin and its raw materials, and markets in Western and Northern Europe. Against this backdrop, and in view of its ramifications for Armenia’s national security, it is more vital than ever for Yerevan to partner with friendly intelligence services such as those of India to access reliable intelligence on the financing, logistics, and transport of the global drug trade.

Armenia has only recently begun taking steps towards strengthening its counternarcotics intelligence architecture, and India’s support can be beneficial. Armenia does not have a sufficiently equipped, dedicated, and separate counternarcotics intelligence service, with most drug seizures being conducted under the aegis of the anti-smuggling department of the State Revenue Commission of Armenia, which is the government’s primary tax regulation authority and possesses limited intelligence capabilities.[38] The growing scale of the problem, however, has underscored the need for improved counternarcotics intelligence capabilities. Consequently, Armenia partnered with the US State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs to access intelligence and learn strategies to apply to its particular circumstances.[39],[40]

India may similarly build upon its diplomatic relationship with Armenia to equip the latter with the requisite intelligence and security capacities for counternarcotics work, with the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) playing a lead role in this endeavour. The sharing of best practices, expertise, and organisational know-how would reinforce the wider bilateral relationship and expand avenues for intelligence cooperation in counternarcotics.

India’s intelligence networks in key drug-producing regions—the ‘Golden Crescent’[e] of the Middle East and Central Asia and the ‘Golden Triangle’[f] of Southeast Asia—put the country in a position to access counternarcotics intelligence to exchange with Armenian partners.[41] India possesses vast intelligence networks in both these neighbouring regions, and intelligence on trafficking routes from sources could be exchanged with Armenian agencies to yield geopolitical or intelligence returns.

As with the issue of emerging technologies, intelligence cooperation between India and Armenia in counternarcotics may be better managed through the establishment of robust and impenetrable channels of bilateral liaison, facilitating the seamless sharing of sensitive information while securing it from external or internal compromise. While the transnational character of counternarcotics in the region indicates some latitude for intelligence cooperation with Armenia within minilateral frameworks—for instance, alongside countries like Iran and Georgia, which face similar challenges—liaison through multilateral international platforms such as the Interpol or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would risk diluting India’s efforts to grow its regional influence through its access to critical intelligence.[42],[43] Managing the flow of intelligence on counternarcotics bilaterally or minilaterally would allow for the dissemination of intelligence within smaller groupings, mitigating against the risk of exposure and subsequent counterintelligence failures.

Conclusion

A combination of geopolitical factors have drawn New Delhi and Yerevan into a closer strategic partnership in recent years. This relationship can be deepened by exploring prospects for intelligence cooperation. This brief has sought to do so through an analysis of internally generated opportunities in Armenia that facilitate such a liaison and external factors that pose challenges and necessitate intelligence cooperation.

Shifting regional geopolitics have led to the Armenian government undertaking an overhaul of its intelligence apparatus, establishing a new foreign intelligence service, and restructuring the NSS to better tackle new counterintelligence and internal security challenges. These changes present opportunities for Indo-Armenian intelligence cooperation in areas such as organisational structuring and inter-agency coordination. Additionally, Armenia’s efforts to position itself as a technological powerhouse in the region and beyond enables intelligence cooperation between India and Armenia in a space where there is clear convergence in their geopolitical interests.

The Türkiye-Pakistan nexus in the Caucasus has also driven intelligence cooperation between India and Armenia, and transnational drug trade is a shared concern. India can support its Armenian partners by helping to strengthen the latter’s intelligence capabilities through liaison with India’s primary drug control law enforcement agency as well as through New Delhi’s wide-ranging intelligence networks in the Golden Crescent and Golden Triangle.

India and Armenia are yet to fully explore the untapped potential of their relationship. Both countries hold the power to reshape the regional order and articulate their new national identities at a time of unprecedented geopolitical flux. Intelligence liaison between India and Armenia can go a long way in solidifying this incipient relationship and strengthen the bilateral security partnership.

Endnotes

[a] Derived from the Classical Armenian word tasn, meaning ‘ten’. The tasinarioi were intelligence-gathering and specialist reconnaissance formations of ten tasked with securing the imperial periphery, collecting sensitive information, and harassing foreign raiders.

[b] The formation of bilateral or multilateral/minilateral partnerships focused on discrete issues.

[c] Based on anonymous interviews with Armenian officials at the Yerevan Dialogue, organised in September 2024 by the Observer Research Foundation and Armenia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The conference brought together policymakers, academics, and the private sector to discuss issues of regional and global interest.

[d] This is similar to the AUKUS Defence Investors Network that provides the British, US, and Australian governments closer access to ‘clean capital’ and cutting-edge defence technologies.

[e] The largest heroin-producing region of the world, driven primarily by the significant poppy cultivation in Afghanistan.

[f] The Golden Triangle is likely to overtake the Golden Crescent in heroin production owing to the rising poppy cultivation and drug manufacturing amid Myanmar’s civil war.

[1] Nilanthan Niruthan, “The Indic Roots of Espionage: Lessons for International Security,” The SAIS Review of International Affairs, August 21, 2019, https://saisreview.sais.jhu.edu/the-indic-roots-of-espionage-lessons-for-international-security/

[2] Nike Koutrakou, “Eyes of the Emperor' and 'Real Spies'. Stories of Espionage in Byzantine Writings,” Leidschrift Historical Journal 30, 2015: 50.

[3] The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, Government of Armenia, https://www.primeminister.am/en/press-release/item/2022/12/08/Cabinet-meeting/

[4] Shalva Dzebiashvili and Lia Evoyan, “Why New Democrats Fail: Preserving the Old Role of Siloviki in Armenia,” in Shifting Security and Power Constellations in Central Asia and the Caucasus, ed. Marie-Sophie Borchelt Camêlo and Aziz Elmuradov (Baden-Baden: Nomos Publishing House, 2024), 177.

[5] ““Armenia is Separating from Russia” - Opinion on Reforms in the National Security Service,” JAM News, January 12, 2024, https://jam-news.net/opinion-on-reforms-in-the-national-security-service-of-armenia/

[6] The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, Government of Armenia, https://www.primeminister.am/en/press-release/item/2022/12/08/Cabinet-meeting/

[7] Naira Bulghadarian, “Armenia’s First Foreign Intelligence Chief Named After ‘Training’,” Radio Free Europe, October 5, 2023, https://www.azatutyun.am/a/32624669.html

[8] Bulghadarian, “Armenia’s First Foreign Intelligence Chief Named After ‘Training’”

[9] Gabriel Gavin, “The Secret Arms Deal That Cost Putin an Ally,” POLITICO, June 13, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/leaked-documents-reveal-belarus-armed-azerbaijan-against-ally-armenia/

[10] “Armenia’s Foreign Intelligence Chief Warns of External Threats to Armenia’s Sovereignty and Independence,” Asbarez, May 29, 2024, https://asbarez.com/armenias-foreign-intelligence-head-warns-of-external-threats-to-armenias-sovereignty-and-independence/

[11] Hamidreza Azizi and Daria Isachenko, “Turkey-Iran Rivalry in the Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus,” German Institute for International and Security Affairs, 2023, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2023C49/

[12] Archishman Goswami, “Partners in Unfamiliarity: India-Gulf Intelligence Relations in a Changing West Asia,” Observer Research Foundation, March 14, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/partners-in-unfamiliarity-india-gulf-intelligence-relations-in-a-changing-west-asia

[13] Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/cabinet-approves-signing-of-an-mou-between-india-and-armenia-on-cooperation-in-the-field-of-sharing-successful-digital-solutions-implemented-at-population-scale-for-digital-transformation/

[14] Craig Smith, “Soviet Mainframes to Silicon Mountains: Armenia as a Tech Powerhouse,” Forbes, December 12, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/craigsmith/2023/12/08/soviet-mainframes-to-silicon-mountains-armenia-as-a-tech-powerhouse/

[15] Smith, “Soviet Mainframes to Silicon Mountains: Armenia as a Tech Powerhouse”

[16] Raffi Elliot, “Armenia Transformation Strategy 2050 Briefly Explained,” The Armenian Weekly, September 23, 2020, https://armenianweekly.com/2020/09/23/armenia-transformation-strategy-2050-briefly-explained/

[17] “Vision India@2047: Transforming the Nation's future,” Lok Sabha Secretariat, December 2023, https://loksabhadocs.nic.in/Refinput/New_Reference_Notes/English/16012024_112431_102120474.pdf

[18] Gatra Priyandita, Bart Hogeveen and Ben Stevens, “State-Sponsored Economic Cyber-Espionage for Commercial Purposes: Tackling an Invisible but Persistent Risk to Prosperity,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, December 16, 2022, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/state-sponsored-economic-cyberespionage

[19] Konark Bhandari, Arun K. Singh, and Rudra Chaudhuri, “India and the United States’ Good Bet: One Year of the U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET),” Carnegie India, June 12, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/06/india-and-the-united-states-good-bet-one-year-of-the-us-india-initiative-on-critical-and-emerging-technology-icet?lang=en

[20] Rezaul Laskar, “India, UK Launch Joint Tech Security Initiative,” Hindustan Times, July 25, 2024, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-uk-launch-joint-tech-security-initiative-101721876539784.html

[21] KP Wright, “Cold War Reconnaissance Flights along the Berlin Corridors and in the Berlin Control Zone 1960–90: Risk, Coordination and Sharing,” Intelligence and National Security 30, no. 5 (2014):616.

[22] Siranush Melikyan, “Fast-Tracking Armenia-India Military Cooperation,” Observer Research Foundation, May 17, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/fast-tracking-armenia-india-military-cooperation

[23] Bronte Munro, “How AUKUS Plans to Outpace China with Defence Tech Investments,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, February 23, 2024, https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/how-aukus-plans-outpace-china-defense-tech-investments

[24] Emmanouil Fragkos, “Turkish Funding for Anti-India Extremism,” European Parliament, January 28, 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2021-000549_EN.html

[25] “Armenia Reaffirms Support For India Over Its Territorial Dispute With Pakistan,” Radio Free Europe, August 16, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/armenia-kashmir-nagorno-karabakh/31412485.html

[26] Naveed Siddiqui, “FO Rejects ‘Baseless, Claim by Armenian PM About Pakistani Forces’ Involvement in Karabakh Conflict,” Dawn, October 17, 2020, https://www.dawn.com/news/1585565

[27] The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, Government of Armenia, https://www.primeminister.am/en/statements-and-messages/item/2020/10/14/Nikol-Pashinyan-message-to-the-nation/

[28] “Turkey to Engage Pakistan Over Officially Joining Kaan project,” Janes, August 8, 2023, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/air/turkey-to-engage-pakistan-over-officially-joining-kaan-project

[29] Paul Iddon, “A traditional Russian Ally Snubbed Moscow's Latest Fighter Jets for Competitors from Pakistan and Turkey,” Business Insider, March 7, 2024, https://www.businessinsider.in/international/news/a-traditional-russian-ally-snubbed-moscows-latest-fighter-jets-for-competitors-from-pakistan-and-turkey/articleshow/108280967.cms

[30] Abhinav Pandya, “How India Brought the Saudi-Turkish Rivalry to Kashmir,” The National Interest, March 1, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/middle-east-watch/how-india-brought-saudi-turkish-rivalry-kashmir-179027

[31] “Indian Intelligence Agencies Keep an Eye on Al-Qaeda Linked Turkish Group Expanding in Nepal,” Livemint, February 28, 2021, https://www.livemint.com/news/world/alqaeda-linked-turkish-group-in-nepal-under-lens-of-india-intelligence-agencies-11614473811333.html

[32] Tigran Yepremyan, “Armenia, India, and the Possibility of an ‘Indo-European Security Supercomplex’,” Observer Research Foundation, May 16, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/armenia-india-and-the-possibility-of-an-indo-european-security-supercomplex

[33] John Daly, “Armenia Plans to Use Iranian Ports to Reach India,” Jamestown Foundation, January 23, 2024, https://jamestown.org/program/armenia-plans-to-use-iranian-ports-to-reach-india/

[34] “Armenia Seizes $250 Million Worth Of Cocaine,” Barrons, May 17, 2023, https://www.barrons.com/news/armenia-seizes-250-million-worth-of-cocaine-d5252d34

[35] “Russian War Against Ukraine Changes Heroin Routes to EU, Says 2024 EU Drug Markets Analysis from EMCDDA and Europol,” EU Neighbours East, January 29, 2024, https://euneighbourseast.eu/news/latest-news/russian-war-against-ukraine-changes-heroin-routes-to-eu-says-2024-eu-drug-markets-analysis-from-emcdda-and-europol/

[36] “EU Drug Market: Heroin and other Opiods – Trafficking and Supply,” European Union Drugs Agency, https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/eu-drug-markets/heroin-and-other-opioids/trafficking-and-supply_en

[37] “Armenia,” Global Organised Crime Index, https://ocindex.net/country/armenia

[38] “First Time in Two Years, Armenian Customs Agents Find Inbound Fentanyl,” Armenpress, January 23, 2024, https://armenpress.am/en/article/1128641

[39] “U.S. Offers Armenian Law Enforcement Best Practices in Counter-Narcotics,” US Embassy in Armenia, June 19, 2017, https://am.usembassy.gov/counter-narcotics/

[40] “Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs: Armenia,” US State Department, https://www.state.gov/bureau-of-international-narcotics-and-law-enforcement-affairs-work-by-country/armenia-summary/

[41] Hai Luong, “How Myanmar Became the Opium Capital of the World,” East Asia Forum, May 16, 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/05/16/how-myanmar-became-the-opium-capital-of-the-world/

[42] Syed Fazl-e-Haider, “Central Asia Cracks Down on Drug Trafficking,” Jamestown Foundation, April 16, 2024, https://jamestown.org/program/central-asia-cracks-down-on-drug-trafficking/

[43] “Georgia Busts Transnational Drug Trafficking Ring,” Civil Georgia, July 21, 2023, https://civil.ge/archives/552936

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Archishman Ray Goswami is a Non-Resident Junior Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation. His work focusses on the intersections between intelligence, multipolarity, and wider international politics, ...

Read More +