-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The contours of global supply chains in the 2020s and beyond will be shaped by the evolving understandings of “trust.”

This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2021.

Supply chains for critical and emerging technologies face mounting scrutiny in the wake of two related disruptions — one precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the other by tensions between the world’s two largest economies, China and the US. Decades of efficiency-driven shifts that gave rise to the global supply chain have also made them fragile and riddled with bottlenecks. At the same time, the need to verify the “trustworthiness” of suppliers has created an added layer of scrutiny.

Decades of efficiency-driven shifts that gave rise to the global supply chain have also made them fragile and riddled with bottlenecks.

However, what does the concept of “trusted supply chains” mean in this evolving context? Depending on the “who” and “where” attached to this question, “trusted” can variously mean secure, transparent, adaptive, ethical or stable.

This brief will identify characteristics of global supply chains for critical technologies, highlight the various ways different actors define “trusted supply chains” and then present some core characteristics of this emerging narrative.

The evolution of global supply chains is linked to what economist Richard Baldwin characterised as globalisation’s “unbundlings” — the unbundling of production and consumption triggered by the industrial revolution (1820s-1990); and the unbundling of stages of production, or offshoring triggered by the information and communications technology revolution (1990s-present). Baldwin also proposed a “third unbundling”, the unbundling of physical labour from the individual due to developments in the internet of things (IoT), robotics and other emerging technologies that will enable workers in one location to perform physical tasks in another.

Modern supply chains for many technologies are, therefore, multi-layered and vast, ning several countries, with each specialising in specific components and services.

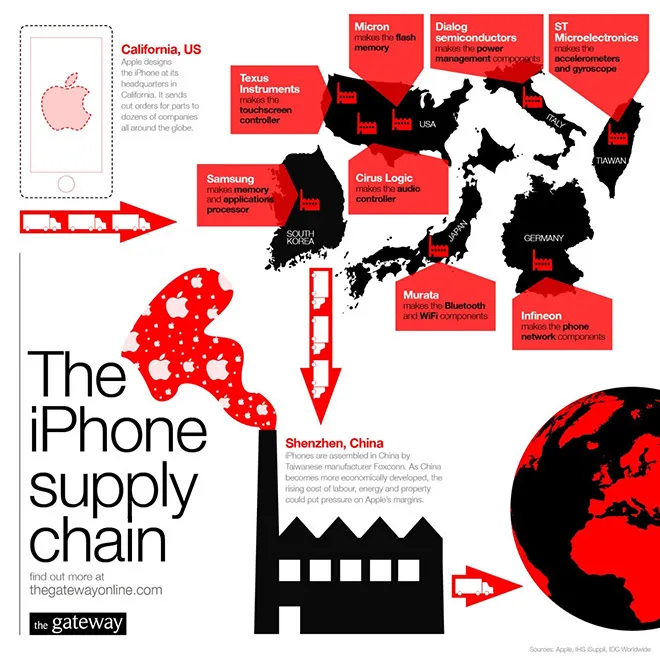

One need only look at the humble iPhone to get a sense of the scale and complexity of these supply chains.

“Increasingly, firms across advanced and developing countries add value along these global supply chains by completing a specific task associated with the production of a finished product and then exporting it. This may be an important part or component required in the production of a good. It may even be a service that is a vital intermediate input in further production.”

One need only look at the humble iPhone to get a sense of the scale and complexity of these supply chains. As a starting point, look to Apple’s Supplier List, which includes 200 suppliers in 25 countries.

Figure 1: The iPhone Supply Chain

Source: The Gateway

Source: The Gateway

The mind-boggling complexity of a single smartphone is a microcosm for how global technology supply chains function; the disruption in supply of a single component can disrupt the entire chain. Semiconductor supply chains, for instance, are notoriously brittle, and the world is currently seeing a global chip shortage due to the combined impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration’s blacklisting of Chinese semiconductor firms (many of whom supply US tech giants, like Apple), and a shortage of shipping vessels and airfreight.

While disenchantment with globalisation is by no means a new phenomenon, the urgency around so-called “trusted supply chains” has intensified over the past two years.

The combined storms of trade wars and pandemics have led to a paradigm shift in the narratives around the global supply chain. While disenchantment with globalisation is by no means a new phenomenon, the urgency around so-called “trusted supply chains” has intensified over the past two years.

A relatively new entrant in the global geopolitical lexicon, the concept of trust in supply chains has a history in defence and industrial management.

A relatively new entrant in the global geopolitical lexicon, the concept of trust in supply chains has a history in defence and industrial management.

The use of the term “trusted supply chains” (and its permutations) within its current contours has truly taken off in the past two years. Amongst technology multinationals, the term is used to reassure customers and clients, and signal reliability to regulators. Lenovo’s ‘Trusted Supplier Programme,’ for instance, emphasises its Kafkaesque audit system, including a 200-point questionnaire.

This competitive aspect is present in political narratives as well. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, for instance, pitched India as a favoured destination for post-pandemic reshoring of supply chains: "

The October 2020 White Paper by the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission (CSC) takes a similar stance, promoting globally “American and partner companies in the face of Chinese anti-competitive behaviour in global markets”.

The EU’s efforts to build trusted supply chains hinges on strong and competitive European alternatives to critical and emerging technologies like microprocessors, quantum communications infrastructure, 5G and IoT, as well as the identification and management of “untrusted” third party vendors.

The Australian parliament’s report on the impact of the pandemic on trade makes seven mentions of “trusted supply chains,” and one of its recommendations proposes that the country be a “trusted and transparent partner of choice for like-minded nations.”

Security and self-reliance march in tandem with narratives on trusted supply chains. The European Union (EU) vision for a “Digital Europe” aims for “robust European industrial and technology coverage of key parts of the digital supply chain.”

Resilience in terms of strength and reliability of institutions and policies is a component of trusted supply chains in other state narratives as well.

The Australian parliament’s report and CSC White Paper at various instances contain overlaps between ideas of trust and those of resilience. “The supplier should not be subject to major commercial or financial risk or the risk of supply interruptions due to factors such as political insecurity, armed conflict, corruption, administrative malpractice, government intervention, arbitrary policy or regulatory enforcement or vulnerability to natural and environmental disasters,” the Australian report says.

The Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s White Paper on International Economy and Trade 2020 also prioritises “resilient supply chains” that are flexible in the face of future shocks.

Resilience in terms of strength and reliability of institutions and policies is a component of trusted supply chains in other state narratives as well. Case in point is the following statement by Malaysia’s former Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng, “Our institutional reforms have also made our institutions more trustworthy and transparent.”

Defined in these various ways, what do “trusted supply chains” mean? Four threads emerge.

Security: The ability to predict, monitor and respond to threats that may affect the continuity of supply chains. Security is sometimes conflated with trust, but at other times (as in several of the documents cited in this brief) it is but one element of a trusted supply chain. This lack of clarity plagues the tech industry as well. As a post on IBM’s blog notes, “There is no single, functional definition of supply chain security. It’s a massively broad area that includes everything from physical threats to cyber threats, from protecting transactions to protecting systems, and from mitigating risk with parties in the immediate business network to mitigating risk derived from third, fourth and “n” party relationships.”

Transparency: Transparent decision processes, regular audits and responsiveness to requests for information are a staple of the “trusted supply chain” concept. This extends to the governments of the countries that suppliers are based in. Clear laws governing flows of goods and services, and transparency in governance practices and in the arbitration of legal disputes all fall under the aegis of this thread.

Resilience: Namely the ability of supply chains to recover from shocks, whether they be from natural disasters, changes in the security and economic policies of supplier nations, et al. Where security and transparency may place specific obligations on suppliers, resilience is a quality of the network in its entirety.

Likemindedness: Perhaps the least-clearly defined of the four, likemindedness appears to capture two broad ideas. The first is similarity in ideologies and, by extension, legal and political systems. Australia and the US, for instance, both emphasise democracy and open societies as a requirement to build trusted supply chains.

The result of the increasing, politically charged scrutiny of global technology supply chains may well transform trust into one of the most valued currencies in international relations. In this vein, this brief noted the competitive aspect of the “trusted supply chain” narrative, where governments and tech giants alike have emphasised their trustworthiness as a core competency that distinguishes them in the global market.

The use of the term “trust” in this context can serve as a shorthand for reliability, resilience or continuity, call for the strengthening of the security of supply chains, or target adversaries.

Trusted supply chains will likewise become a mainstay in the formation of new coalitions centred on critical and emerging technologies. However, observers should not assume that this term captures the same ideas amongst the myriad of actors that have begun to use it. The use of the term “trust” in this context can serve as a shorthand for reliability, resilience or continuity, call for the strengthening of the security of supply chains, or target adversaries.

While the drive for efficiency and lower factor costs prompted the globalisation of supply chains in the past three decades, the contours of global supply chains in the 2020s and beyond will be shaped by the evolving understandings of “trust.”

Richard Baldwin, “Globalisation: The Great Unbundling(s),” Economic Council of Finland, 20 September 2006; Richard Baldwin, The Great Convergence: Information technology and the New Globalisation (Harvard University Press: November 2016).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Trisha Ray is an associate director and resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoTech Center. Her research interests lie in geopolitical and security trends in ...

Read More +