Image Source: Getty

This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2025

Over the past century, international trade in goods and services has expanded more than 40-fold, increasing from a fraction of global output in 1904 to over 59 percent of world GDP today.[1] Countries that are deeply integrated into global value chains, trading in higher-value and more complex goods, are among the most prosperous nations today. The ability to move up the value chain—from exporting raw materials to producing high-value manufactured goods—has defined the development trajectories of fast-growing economies such as South Korea, China, and Singapore.

This prosperity remains unevenly distributed. A country’s share of global production and the complexity of its exports directly correlate with its level of economic development. The world’s poorest economies tend to trade lower-value primary goods and face constraints that limit manufacturing growth and industrial diversification. As a result, developing countries, home to nearly 90 percent of the world’s population, struggle to compete on equal footing in international trade.

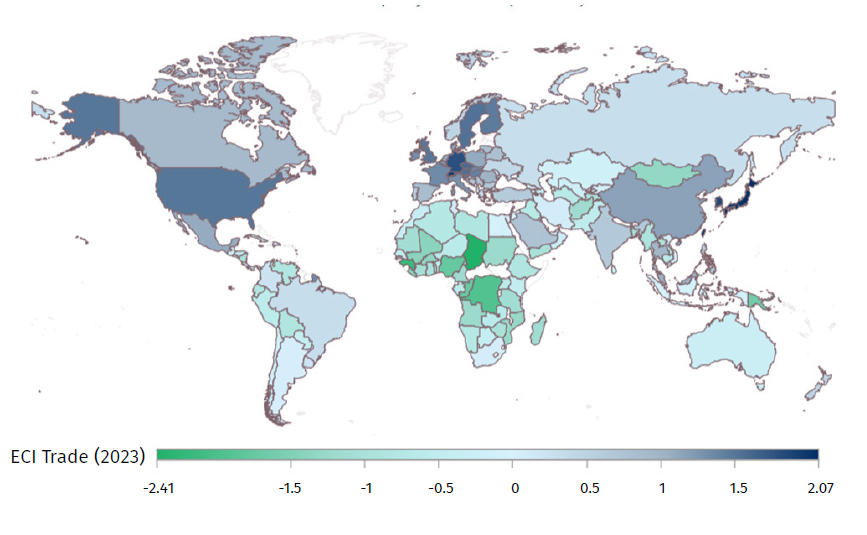

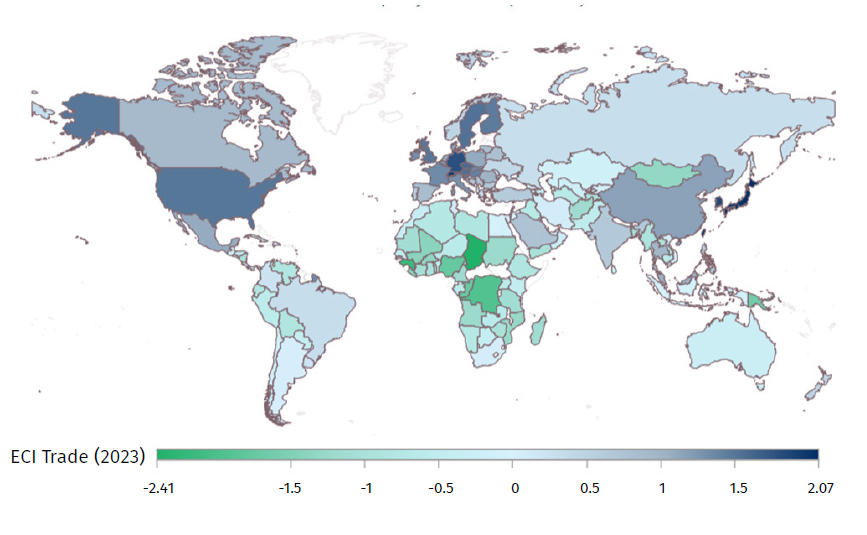

Figure 1: Country Ranking by Level of Economic Complexity in Trade (2023)

Economic Complexity Index Trade (ECI Trade)

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).[2] * International borders as they appear in the original.

Note: The Economic Complexity Index (ECI), compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) is a measure of the relative knowledge intensity of an economy. EC metrics incorporate information about the level of sophistication of each product in a country’s export basket. See: https://oec.world/pdf/multidimensional-economic-complexity-and-inclusivegreen-growth.pdf

Figure 1 illustrates these patterns. In the graph, the highest number to the right of zero on the scale reflects the greatest economic complexity in trade, as denoted by the intensity of the blue colour. Conversely, the numbers to the left of zero on the scale indicate lower economic complexity, represented by the colour green. Unsurprisingly, LDCs and developing countries score the lowest due to the nature of their exports, illustrating how a country’s share of global production and the complexity of its exports are correlated with its level of economic development.

For many, addressing this inequality is not just a trade issue—it is an economic and social imperative. Over 700 million people in developing economies continue to live in extreme poverty.[3] Without expanded access to global markets, economic opportunities remain limited, fuelling increased migration pressures, for example from Africa to Europe or from Latin America to North America.

While national-based trade policies can help countries integrate into global markets, expand industrial bases, and attract investment, they require a normative framework such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), which has established a rules-based global trade system to foster growth worldwide. However, recent shifts in trade dynamics are threatening past progress.[4]

The rise of bilateral, regional, and plurilateral trade agreements can complement and reinforce the WTO-led multilateral system, rather than weaken it. While these agreements provide tailored solutions for specific regions and trade partners, their effectiveness fundamentally relies on a strong, rules-based global framework. Likewise, a well-functioning WTO benefits from regional trade arrangements that foster economic integration and streamline trade processes at a smaller scale. Instead of creating fragmentation, there is a need for greater synergy between these systems—leveraging bilateral and regional agreements to strengthen multilateral trade governance, particularly through instruments like the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). By aligning these frameworks and incorporating technological advancements, trade efficiency can be improved in a manner that benefits both individual nations and the broader global economy.

This essay examines three key measures that can help break down the biggest barriers to trade in developing countries:

- Implementing the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) to lower costs and streamline trade processes.

- Harnessing trade logistics charters to commit trade actors to measurable efficiency improvements.

- Leveraging technology through revolutionary platforms like the Trade Worldwide Information Network (TWIN) to modernise and digitise trade.

Threats to Trade Growth in Developing Countries

Developing countries face massive structural and policy-related constraints that increase trade costs and limit competitiveness. These challenges—ranging from infrastructure gaps to bureaucratic inefficiencies—must be addressed to unlock trade-driven economic transformation. High transport and logistics costs (and times) in low-income countries increase trading expenses, making products less competitive globally. Trade documentation and border formalities that are highly bureaucratic and inefficient also contribute to the burden of trading. According to the World Bank, inefficient border procedures alone can increase trade costs by over 25 percent,[5] leading to delays to the clearing of goods which can last as long as 28 days in some ports.[a]

Limited technology-enabled processing infrastructure further restricts value addition, reinforcing raw material-driven exports structures. For instance, despite Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire producing over 50 percent of the world’s cocoa, they export 70 percent of their beans unprocessed, leaving over 79 percent of the final market value in the hands of foreign manufacturers and retailers.[6] These export structures leave little room for enhancing economic benefits for over six million smallholder farmers who grow the beans.

Another growing challenge is regulatory shifts in global trade that is increasing complexities and compliance costs, particularly climate-focused policies like the European Union’s (EU) Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).[7] While designed to promote sustainability, CBAM, when it takes effect from January 2026, would disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)[8] by imposing tariffs on carbon-intensive imports such as steel, cement, and aluminium. Mozambique, for example, relies on the EU for 97 percent of its aluminium exports,[9] making the country highly vulnerable to this policy.

Geopolitical shifts and protectionist patterns also threaten developing economies. The increasing use of tariffs as political leverage—as seen in the 2018-2019 US-China trade war, which drove up costs of impacted goods by roughly 1:1 with tariff hikes[10]—disrupts supply chains and increases global inflation. More recently, US proposals for flat-rate tariffs on all imports put programmes like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA)[1b] at risk, potentially weakening Africa’s trade foothold in US markets.

Finally, insecurity and regional instability further disrupt trade. For instance, the decline of democratic institutions in Africa’s Sahel region, instability in the Middle East, and the conflict between Russia and Ukraine have affected trade infrastructure and contributed to global inflation. The withdrawal in January 2025 of Sahel countries, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) hampers the development of regional value chains, which are essential for trade growth.[11]

These factors collectively increase the time and cost of trading, making it more difficult for developing countries to scale their economies.

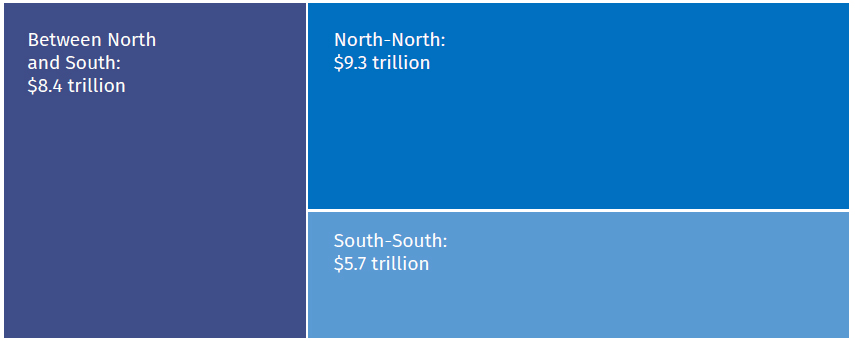

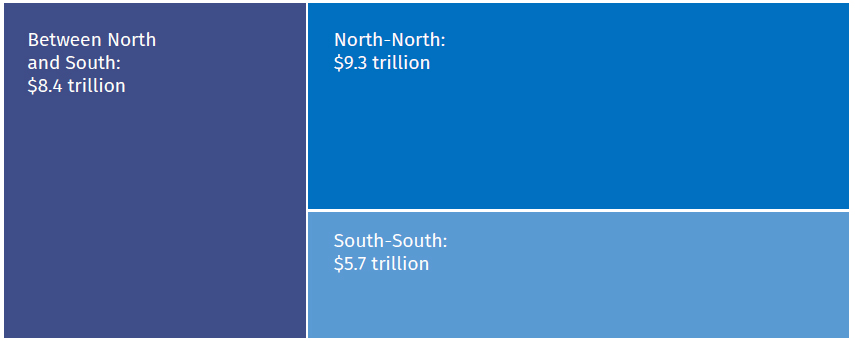

Figure 2: Trade Data: North – North, South – South, and North – South

In 2023 South-South trade was $5.7 trillion, a 7 per cent drop on 2022 Global trade flows, 2023

Note: North refers to developed economies, South to developing economies. Trade is measured from the export side. Deliveries to ship stores and bunkers as well as minor and special-category exports with unspecified destination are not included.

Source: UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2024[12

What Needs to be Done?

Establishing systems to streamline trade flows is crucial for success. The WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) was designed to facilitate trade by simplifying, modernising, and harmonising trade procedures.[13] The agreement, which came into force in 2017, has the potential to reduce trade costs by up to 23 percent for developing countries, increasing global trade by US$1 trillion annually.[14] However, implementation remains uneven. While developed countries have achieved 100-percent implementation as of 2025,[1c] developing countries lag behind at 60 percent, and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) even slower at 30 percent.[15] Additionally, out of 110 ratifying members, 72—mostly from developing countries— have overdue notifications and require either additional time, technical assistance, financial support, or all three, to implement selected provisions.[16]

Beyond policy commitments, urgent action is required to translate intent into real cost and time reductions. In some developed economies, goods clear customs within hours; in certain developing countries, it takes up to 28 days. Addressing this gap requires innovative, costeffective solutions. Beyond technical assistance support from actors like the World Bank, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and International Trade Centre (ITC), tools such as trade logistics charters and cutting-edge digital trade solutions like the Trade Worldwide Information Network (TWIN) can be game changers. These must all be underpinned by strong political will and increased cooperation.

Transforming Commitments into Action Through Trade Logistics Charters

While many developing countries have established National Trade Facilitation Committees (NTFCs) to coordinate trade-related reforms, most are underfunded and lack enforcement power. To bridge this gap, governments and stakeholders can adopt Trade Logistics Charters, which transform policy intent into actionable commitments with clear targets and accountability mechanisms.

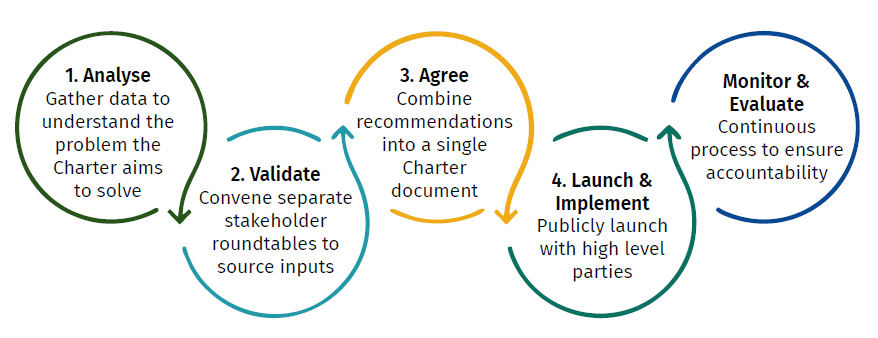

A Port Improvement Charter, for example, creates binding commitments among port authorities, regulatory agencies, and private sector actors to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Key steps in the process include a diagnostic assessment where activities such as a Time Release Study are conducted to identify inefficiencies from vessel arrival to cargo clearance; stakeholder engagement and validation workshops to agree on key performance indicators (KPIs) and set reform targets; and finally, public commitment through a launch by top political leadership, with the Charter signed by key stakeholders to ensure enforcement accountability.

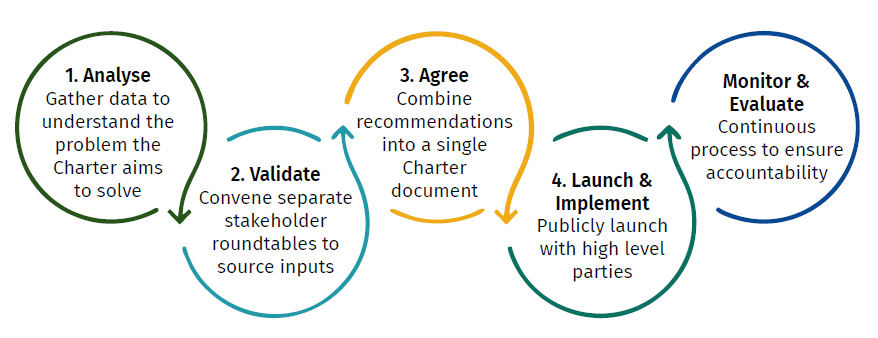

Figure 3. Five Steps to Develop a Port Improvement Charter

Commitment to implementing this process will have maximum impact on reducing trade costs, fuel economic activity, and ultimately expand government revenue streams.

Source: Author’s own

This approach has already yielded results. Kenya’s Mombasa Port Charter transformed it into one of Africa’s top-performing ports, increasing efficiency and reducing clearance time with container times reduced from 10 to four days.[17] Inspired by this, Zanzibar[18] and The Gambia[19] have since adopted similar processes.[d] Mombasa has shown that improved efficiency can unlock private investment into trade logistics infrastructure, creating a ripple effect for broader economic growth.

Harnessing Technology for Trade Transformation

To accelerate trade reforms, developing countries must leapfrog outdated processes and embrace digital solutions. Research from the Oxford Review of Economic Policy underscores the centrality of digital technologies in transforming industries, supply chains, and trade networks.[20] The automation of processes once reliant on low-cost labour is shifting jobs away from traditional outsourcing destinations.[e]

The Trade Worldwide Information Network (TWIN), a Distributed Ledger Technology developed in 2020,[21] has the potential to disrupt digital trade. Developed by a consortium of organisations that include the IOTA Foundation, Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation, TradeMark Africa, World Economic Forum, Chartered Institute of Exports, and The Tony Blair Institute, TWIN aims to digitally connect national trade systems across borders, replacing outdated, paper-based trade documentation with digital, seamless, secure, and transparent systems. Early evidence shows it could reduce trade costs by up to 20 percent by modernising cross-border trade procedures.[22]

Crucially, TWIN directly addresses some of the information-based provisions and mechanisms of the WTO TFA, including electronic single windows,[f] trade portals, advance ruling, and preclearance. It also includes procedures or programmes such as risk management, Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) programmes, and border agency cooperation, particularly at the cross-border level.[23]

Following successful pilots between Kenya and the Netherlands, efforts are underway to implement TWIN across 30 African countries over the next seven years and to set up TWIN ecosystems in Asia and the Americas.[24] As a strong South-South trade initiative, it offers a scalable model for enhancing intra-regional trade and reducing dependence on developed world-centric trade logistics.

Strengthening Trade Cooperation and Political Will

At the core of all these solutions lies political will and strategic cooperation, particularly among developing nations. While multilateral trade systems are ideal, the reality of a fragmented global trade order requires bolder action from governments in the Global South—this includes prioritising South-South trade cooperation over dependency on developed economies.[25],[26]

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) exemplifies this shift. Once fully implemented, the AfCFTA is projected to boost intra-African trade by over 50 percent, by some estimates lifting 30 million people out of poverty and increasing Africa’s GDP by US$450 billion by 2035.[27] However, realising these benefits requires stronger coordination, infrastructure investments, and effective implementation of trade-friendly policies.

Many transformational opportunities can be realised through stronger political will. For example, Africa’s Grand Inga Dam project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo could generate 44,000 MW of hydroelectric power—enough to supply 40 percent of Africa’s energy needs.[28] However, despite being launched in 2013, the project remains stalled due to political fragmentation and lack of coordinated investment. Similar untapped prospects exist across sectors, reinforcing the need for greater leadership and commitment to regional cooperation.

Conclusion: From Intent to Impact

Good intentions and commitments alone will not drive change—deliberate action, technologydriven solutions, and strengthened regional cooperation are necessary to transform trade in developing countries. Trade Logistics Charters can drive domestic efficiencies, while TWIN offers a digital pathway to streamline cross-border trade. Yet, none of these solutions will work without bold leadership, policy enforcement, and a commitment to greater global and regional economic cooperation.

For developing countries, the way forward is clear: leverage existing multilateral frameworks, modernise trade processes, and deepen South-South trade cooperation. The WTO was built on the foundation of shared prosperity and open trade—in an era of fragmented global trade governance, developing countries must take bold and urgent steps to chart their socioeconomic transformation pathways.

Endnotes

[a] Figures are taken from a 2023 Time Release Study (TRS) conducted at the Port of Banjul in Gambia. (A TRS is a process of tracking and measuring the exact time it takes for goods to be cleared and released from the moment they arrive at a country’s border until they are ready for delivery, allowing them to identify bottlenecks and areas for improvement in the import/export process.)

[b] AGOA is a unilateral trade preference programme for select African countries which grants tariff-free access on certain products to the US market.

[c] To access up-to-date information on the TFA’s implementation progress by members, see TFAF, “Implementation progress by member”, https://tfadatabase.org/en/implementation/progress-by-member

[d] They are being supported by the Tony Blair Institute (TBI), with which this author is affiliated. [e] In the US, for instance, recent AI-driven automation has replaced over 10,000 hours of lemon-squeezing labour in Chick-fil-A fastfood restaurants, signalling the future of labour-intensive work.

[f] Single windows are platforms that enable users to submit transit-related customs documentation through a single online interface as opposed to disparate websites or paper forms.

[l] World Bank, “Trade (% of GDP),” World Bank Open Data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS.

[2] Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), “Economic Complexity Index (ECI) Rankings,” https://oec.world/en/rankings/eci/hs6/hs96?tab=map.

[3] World Bank, “Poverty: Overview,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview.

[4] Peter van Bergeijk, Patrick Bijsmans, and Jan Orbie, eds., Developing Countries and the Crisis of the Multilateral Order (Rotterdam: Erasmus University, 2023), https://pure.eur.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/87015138/Developing_Countries_and_the_Crisis_of_the_Multilateral_Order_Full_Issue.pdf.

[5] World Bank, “Why Transport Costs Are Stifling Growth in Developing Countries,” World Bank Blogs, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/transport/why-transport-costs-are-stifling-growth-in-developingcountries.

[6] Voice Network, Cocoa Barometer 2015 (Amsterdam: Voice Network, 2015), https://voicenetwork.cc/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Cocoa-Barometer-2015-Print-Friendly-Version. pdf.

[7] European Commission, “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM),” Access2Markets, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/news/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanismcbam.

[8] Ana Goicoechea and Megan Lang, “Firms and Climate Change in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Policy Research Working Paper 10644, World Bank, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/40775.

[9] World Bank, “Relative CBAM Exposure Index,” June 15, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2023/06/15/relative-cbam-exposure-index.

[l0] Pablo Fajgelbaum and Amit Khandelwal, “The Economic Impacts of the US-China Trade War,” NBER Working Paper 29315, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2021, revised December 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29315.

[l1] African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), Regional Value Chains and Intra-African Trade, Cairo, Afreximbank, 2023, https://media.afreximbank.com/afrexim/Regional-Value-Chains-and-Intra-African-Trade.pdf.

[l2] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Handbook of Statistics 2024, Geneva, United Nations, 2025, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdstat49_en.pdf.

[l3] World Trade Organization, “Trade Facilitation and Digital Technologies,” https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dtt_e/dtt-tradfa_e.htm.

[l4] World Trade Organization, Trade Facilitation Agreement: Factsheet 2017, Geneva, WTO, 2017, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tradfa_e/tfa_factsheet2017_e.pdf.

[l5] World Trade Organization, “Implementation of the Trade Facilitation Agreement,” WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Database, https://www.tfadatabase.org/en/implementation.

[l6] World Trade Organization, “Overdue Notifications by Member,” WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Database, https://www.tfadatabase.org/en/overdue-notifications/by-member.

[l7] Kenya Ports Authority, Mombasa Port Community Charter, Mombasa, Kenya Ports Authority, 2014, https://www.kpa.co.ke/Documents/Mombasa%20Port%20Community%20Charter.pdf.

[l8] “Mwinyi Unveils New Port Improvement Plan,” Daily News (Tanzania), https://dailynews.co.tz/mwinyi-unveils-new-port-improvement-plan.

[l9] Foroyaa, “Government Launches Trade Logistics Charter to Enhance Trade Efficiency in Gambia,” https://foroyaa.net/government-launches-trade-logistics-charter-to-enhance-trade-efficiency-ingambia/.

[20] Emily Jones and Christopher Adam, “New Frontiers of Trade and Trade Policy: Digitalization and Climate Change,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 39, no. 1 (Spring 2023): 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grac048.

[2l] Twin, “Ecosystem,” https://www.twin.org/ecosystem.

[22] Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, “Unlocking Africa’s Trade Potential: The Twin Digital Trade Platform,” https://institute.global/insights/economic-prosperity/unlocking-africas-trade-potential-the-twindigital- trade-platform.

[23] World Trade Organization, “Implementation Progress by Measure,” WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Database, https://tfadatabase.org/en/implementation/progress-by-measure.

[24] Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, “Unlocking Africa’s Trade Potential”

[25] Observer Research Foundation, “Rethinking the Global Trade Infrastructure,” https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/rethinking-the-global-trade-infrastructure.

[26] Brookings Institution, “Why South-South Trade Is Already Greater than North-North Trade—And What It Means for Africa,” https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-south-south-trade-is-already-greater-than-north-northtrade- and-what-it-means-for-africa.

[27] African Union, “Powering Trade Through AfCFTA: A People-Driven Wholesome Development Agenda,” February 15, 2023, https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20230215/powering-trade-through-afcfta-people-driven-wholesomedevelopment- agenda.

[28] Africa Energy Portal, “World Bank Targets $80B for Africa’s Mega Inga Dam,” https://africa-energy-portal.org/news/world-bank-targets-80b-africas-mega-inga-dam.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV