Image Source: Getty

India is the world's second-largest tobacco producer and consumer. The country has a long history of tobacco consumption, and it is used in a variety of ways, including smoking and smokeless varieties. In addition to cigarettes and bidis, tobacco can also be smoked with devices such as hookahs, cigars, and pipes. Smokeless forms of tobacco include betel quid chewing, khaini, gutka, and snuff. Tobacco use is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in India, such as cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illnesses, accounting for over 1.35 million deaths each year.

Effective efforts that target this demographic can considerably lower overall tobacco consumption rates and enhance community health outcomes.

This article focuses on two age groups: adults (15–49 years old) and adolescents (13–15 years old). Adolescent populations are critical due to the long-term effects of tobacco use on life quality, productivity, and health into adulthood. Adults are frequently the target of programmes for quitting since they constitute most current users. Effective efforts that target this demographic can considerably lower overall tobacco consumption rates and enhance community health outcomes. It can also contribute to achieving SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being)

Tobacco consumption: Trends and patterns

In India, surveys such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) and Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) help to understand the trends and patterns of tobacco consumption. The NFHS provides data on health and family welfare indicators, including tobacco use among men and women aged 15-49. The relevant rounds with data on tobacco consumption range from NFHS-2 (1998-99) to NFHS-5 (2019-21). On the other hand, GYTS is a national survey conducted in schools among students (aged 13–15 years)—four times so far: 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2019. These surveys have some limitations, including the exclusion of out-of-school adolescents and an absence of data on early and late adolescents (ages 10–19).

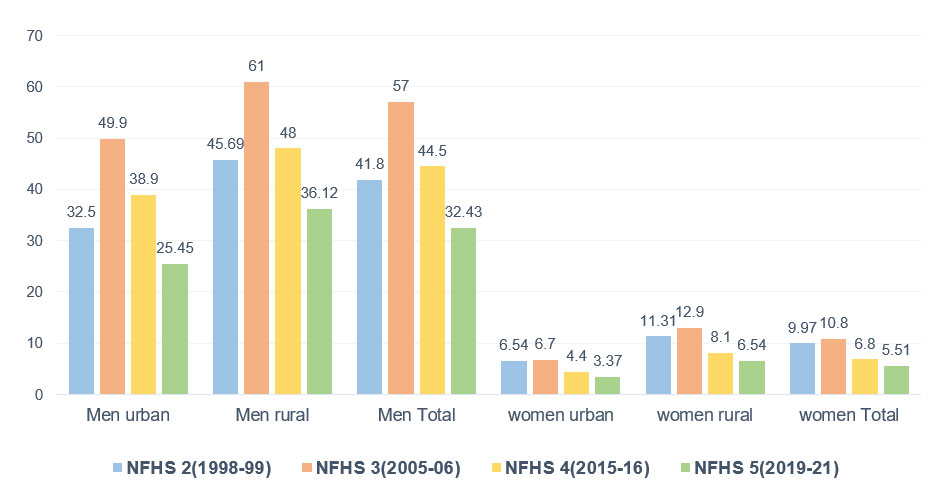

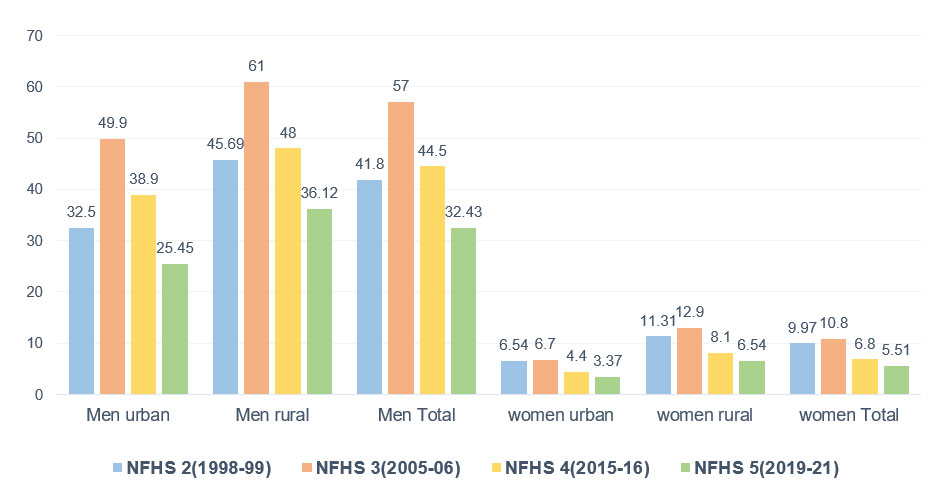

Figure 1: Tobacco consumption on NFHS data among age group 15-49

Source: Compiled by the author [NFHS (1998-99), NFHS (2019-21), NFHS(2005-06), and NFHS(2015-16)].

Figure 1 shows that overall tobacco consumption has decreased in all categories. Between NFHS-2 and NFHS-3, tobacco consumption increased in India from 41.8 percent to 57 percent among men, whereas it increased from 9.9 percent to 10.8 percent among women; this increase can be linked to a variety of factors, such as socioeconomic development, cultural acceptance, marketing, and demographic. However, post-NFHS-3, surveys indicate a decline in tobacco usage across all age groups, especially among younger populations. The decline in tobacco usage since NFHS-3 may be attributed to the approval of an international convention targeting tobacco advertising, promotion, and illicit trade.

Most Indian states have seen a decline in the NFHS-5 survey in male tobacco use, except for Sikkim, Goa, Bihar, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, and Mizoram.

Men's percentage of tobacco usage declined from 38.9 percent to 25.4 percent in urban areas between NFHS-4 and NFHS-5, while it declined from 48 percent to 36 percent in rural regions. For women, it declined from 4.4 percent to 3.3 percent in urban areas and from 8.1 percent to 6.5 percent in rural areas. Most Indian states have seen a decline in the NFHS-5 survey in male tobacco use, except for Sikkim, Goa, Bihar, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, and Mizoram. Preliminary findings from NFHS-5 (2019-21) align with Global Adult Tobacco Survey-2 (GATS-2, 2016-17) to show that the declining trends are not clear throughout the country.

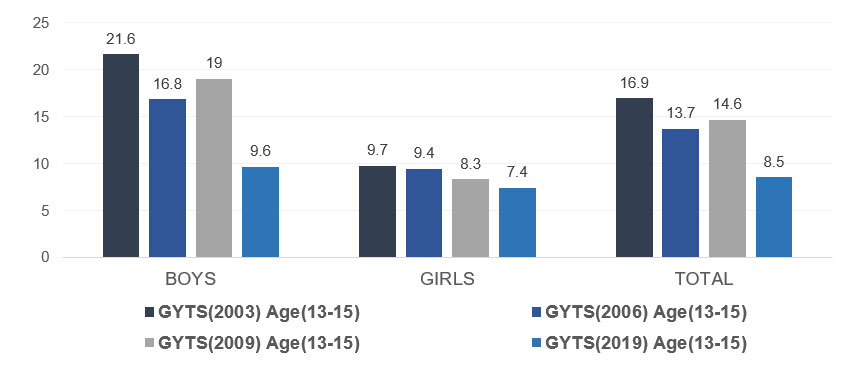

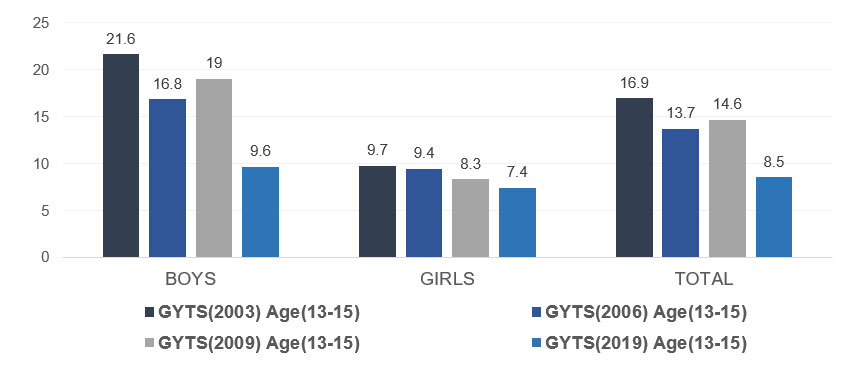

There are significant gender variations in teen tobacco usage, according to the GYTS statistics. The data shows a significant decline in adolescent tobacco use from 2003 to 2019. For example, according to the GYTS-4 (2019) report, tobacco consumption was 7.4 percent among girls and 9.6 percent among boys.

Figure 2: Tobacco use of age group 13–15 years: GYTS India 2003, 2006, 2009, 2019.

Source: Compiled from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Factsheet

Initiatives to increase public knowledge of the risks associated with tobacco use have proven crucial, as seen with anti-tobacco campaigns incorporated into school curriculums. Similarly, anti-tobacco commercials in media and cinemas can reach a broader audience, raise awareness of the adverse effects of tobacco use, and encourage more people to quit. Due to the implementation of stronger laws governing the sale and promotion of its products, children now have limited access to tobacco.

Drivers of tobacco use in India

Tobacco use has become socially acceptable as a result of cultural normalisation, with urban regions having higher cigarette smoking rates (5 percent) than rural areas (3 percent). In contrast, rural areas had a greater rate of bidi and hookah usage (9 percent) than urban areas (5 percent). Rural families with lower incomes now have increased access to bidis due to the flourishing, low-cost bidi businesses. E-cigarettes or vapes are battery-powered devices that vaporise liquid containing nicotine into an aerosol. Although a study reveals that e-cigarettes pose a greater health risk, many use e-cigarettes to quit smoking or as an alternative to traditional methods.

Compared to Indian women with higher levels of education, those with no formal schooling had higher rates of quitting.

Divergent socioeconomic patterns in tobacco use were observed across India, with varying contributing factors across groups. Indian women were found to have greater quitting rates than men, and there were significant differences in cessation rates based on socioeconomic characteristics. Women with higher socioeconomic status have lower ceasing rates, likely due to increasing purchasing power, heightening access to tobacco products, mounting peer pressure, idealising role models, and far-reaching industry marketing. Compared to Indian women with higher levels of education, those with no formal schooling had higher rates of quitting.

Tobacco control policies and their effectiveness

India has several laws and regulations aimed at reducing tobacco use, such as the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) 2003, which is applicable in all states. It prohibits smoking in public areas, around educational institutions, and in advertisements for tobacco products. A stronger implementation of the COTPA Act is the need of the hour to decrease tobacco use among youngsters, especially in educational institutions.

The National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) introduced in 2007–2008 intended to improve the implementation of tobacco control policies under the COTPA. Nonetheless, gaps continue to persist in smokeless tobacco enforcement and cessation initiatives, especially in rural areas where its use is culturally acceptable. Although COTPA and World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) regulations limit it, brand stretching—the practice of masking tobacco products with flavours and sweeteners—remains a public health risk. Inadequate compliance with smokeless tobacco laws paves the way for continued accessibility and promotion, disproportionately impacting vulnerable populations, including women and adolescents.

A stronger implementation of the COTPA Act is the need of the hour to decrease tobacco use among youngsters, especially in educational institutions.

The Prohibition of Electronic Cigarettes Ordinance forbids the production, import, export, distribution, and advertising of e-cigarettes in India after the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) advocated a complete ban on them in May 2019. The use of tobacco and nicotine in food items is also prohibited by Regulation 2.3.4 of the Food Safety and Standards (Prohibition and Restrictions on Sales) Regulations 2011, which means that gutka is prohibited. On 31 May 2023, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) notified amendments to COTPA 2023, updating tobacco control guidelines to issue disclaimers and warnings in online content. Programmes such as mCessation, utilising technology, have become prevalent in helping people quit. Mobile health initiatives provide personalised assistance through applications and text messaging for those trying to quit. Research indicates that by providing easily accessible materials and consistent support, such programmes can drastically boost cessation rates.

The way forward

Raising tobacco taxes is the most effective approach to reducing use, discouraging young people from smoking and encouraging smokers to quit. Implementing public health initiatives like media campaigns, competitions, smoke-free workplaces, and hotlines can change norms and help people quit smoking.

Raising tobacco taxes is the most effective approach to reducing use, discouraging young people from smoking and encouraging smokers to quit.

School-based tobacco use prevention programmes designed for adolescents have the potential to serve two purposes: first, to keep them from falling prey to tobacco company advertisements and marketing, and second, to teach them how to resist peer pressure and motivate their friends and family to quit. Community interventions, including youth involvement and awareness campaigns, can strengthen these programmes. Involving parents, community leaders, and medical professionals fosters a positive environment that reduces youth tobacco use.

The tobacco pandemic is a key obstacle to achieving Sustainable Development Goals. While it is addressed under SDG 3 through the WHO FCTC, India's progress has been slow. Lowering tobacco use and improving public health outcomes require strengthening policies, increasing tobacco prices, and implementing more prevention programmes for vulnerable populations to attain SDG 3 targets and achieve long-term reductions in tobacco use in India.

Manshi is a Research Intern with the Health Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV