Promises

The 2014 report by working group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that the energy sector was responsible for 35 percent of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Despite the efforts of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol, emissions from the energy sector grew more rapidly between 2001 and 2010 than in the previous decade. Energy sector GHG emissions growth accelerated from 1.7 percent a year in the period 1991-2000 to 3.1 percent a year from 2001-2010. The main contribution to this growth came from rapid economic growth in developing countries primarily China and India and the increase in the share of coal in the global fuel mix on account of growth in coal consumption in India and China. The report argued that in the absence of mitigation policies, energy related CO2 (Carbon Dioxide) emissions are likely to increase to 50-70 GtCO2 (giga tonnes of CO2) by 2050. The report concluded that the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere can only be stabilised if global net emissions of CO2 emissions peak and decline towards zero in the long term. In most of the stabilisation scenarios (limiting concentration of CO2 equivalent in the atmosphere to 450-530 ppm [parts per million]), the share of low carbon energy in electricity supply increase from 30 percent to 80 percent. Following the release of the report, China made the following statement in 2014 when the then-President of the United States visited China:

‘China intends to achieve the peaking of CO2 emission around 2030 and make best efforts to peak early and intends to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20 percent by 2030.’

An equivalent statement on carbon peak was not extracted from India in 2014 but pressure began to mount and more recent expert opinion has suggested that India could achieve peak carbon by 2040-45.

Progress

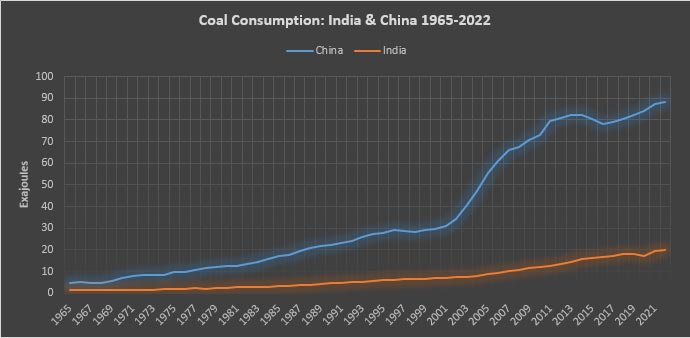

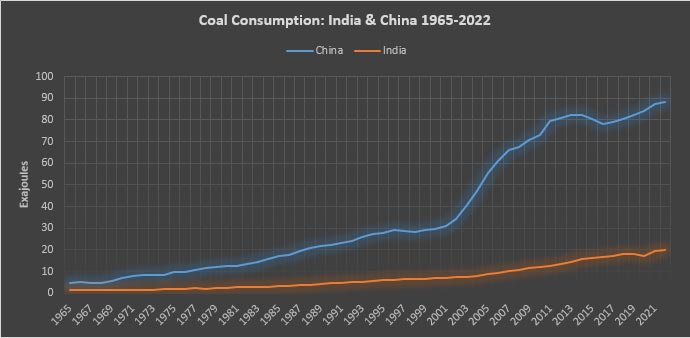

In 2022, the share of non-fossil fuels (nuclear energy, hydropower and renewable energy) in China’s primary energy mix was close to its 2030 target at 18.37 percent. Although India has not committed to a share of non-fossil fuels in its primary energy mix, India derived 11 percent of its primary energy from non-fossil fuels in 2022. Globally, non-fossil fuels accounted for about 18.2 percent of primary energy in 2022, which means over 82 percent of global primary energy came from fossil fuels. Coal’s share in the global primary energy fuel mix increased by 5 percent from 2003-2013, to touch 29 percent, making it the second most important fuel behind oil. Projections made in 2013-14 anticipated that China would remain the single largest coal consumer, accounting for 51 percent of global consumption, while India was expected to take the second place with 13 percent of global consumption overtaking the United States in 2024. This projection has materialised earlier than forecast. More moderate projections expected China’s coal demand growth to decelerate rapidly from 1.3 billion tonnes (BT) representing an annual growth of 6.1 percent in 2005-15 to just 19.5 MT (million tonnes) representing a growth of just 0.1 percent a year in 2025-35 with coal peak in 2030. India and China were expected to contribute 87 percent of global coal growth by 2035. Structural changes and policy measures, such as China’s move from a manufacturing & industry-driven economy to a service and domestic demand-driven economy along with efficiency improvements and stringent environmental policy, were expected to drive a rapid fall in coal demand in China. More ambitious projections expected China to stop importing coal by 2015 and China’s coal demand to start declining by 2016.

Source: Statistical Review of World Energy 2023

Projections made in 2015 celebrating the ‘coal crash’ in the United States argued that the decline in demand for coal in Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD) countries will not be made up by China and India. Drawing on the fact that the price of seaborne thermal coal had weakened the argument was made that much of exported production to China and India would not cover costs and that future prices of coal were unlikely to show much improvement. As China’s coal consumption fell for the first time in 14 years despite economic growth of 7.4 percent, peak coal consumption in China was expected before 2020. The impending coal peak was attributed to a structural shift, driven by China following the western world in beginning to phase out coal.

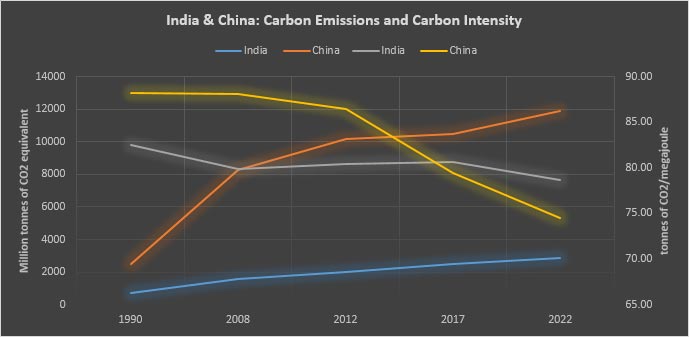

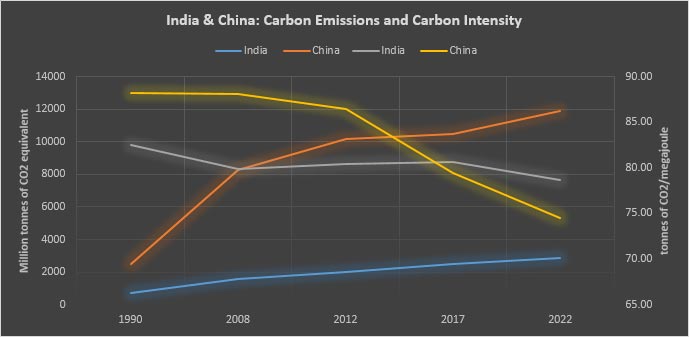

In 2022, China’s coal consumption was 88.41 EJ (exajoules), accounting for over 54.8 percent of global coal consumption. Though growth in coal consumption in China in 2012-22 had slowed down to an annual average of 0.9 percent compared to over 9 percent in 2002-12, it has not peaked as expected by ambitious projections. In 2002-12, China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew at annual average of 10.7 percent and in 2012-22 it grew at an annual average of 6.25 percent. India’s coal consumption grew at an annual average of over 6.2 percent in 2002-12, and at 3.9 percent in 2012-22 while India’s GDP grew at an annual average of 6.9 percent in 2002-12 and at 5.6 percent in 2012-22. Sustained economic growth in China and India without proportional growth in coal consumption indicates an extent of decoupling between carbon emissions and economic growth. This is illustrated by the declining trend in the coal intensity of the Chinese and Indian economies (coal required per unit of GDP) since 2002. In the last two decades, the coal intensity of the Chinese economy has fallen by over 48 percent, while the coal intensity of India’s economy fell by about 18 percent. Services, which are generally less energy-intensive, contribute a much larger share to the economy in India than in China, but India’s coal use efficiency is lower than that of China resulting in higher coal intensity.

Sustained economic growth in China and India without proportional growth in coal consumption indicates an extent of decoupling between carbon emissions and economic growth.

China committed to reducing carbon intensity of its economy (CO2 emissions per unit of GDP) by 40-45 percent during 2005-2020, but China experienced a 3 percent increase in carbon intensity in 2002-09 because gains in efficiency were offset by movement towards a carbon intensive economic structure. If China accelerates the progress towards peak emissions, it could end up increasing carbon emissions as it could potentially drive industries to less efficient countries.

Prognosis

China and India can reduce their emissions and prosper materially only if economic growth is disentangled from energy-related emissions. This is theoretically possible, but the required transformation would impose considerable costs, and drastically re-orienting development towards low carbon growth is not cost-less. In June 2023, the Katowice committee of experts under the UNFCCC acknowledged that developing countries will bear disproportionate cost of decarbonisation in its technical paper on the impacts of the implementation of response measures (to climate change).

Most of the reduction in carbon emission achieved in OECD countries was without any radical policy interventions. Fuels with higher carbon-to-hydrogen ratio, such as firewood, were replaced with cheaper fuels with lower carbon-to-hydrogen ratio such as coal, oil and gas. Some countries in OECD have achieved an annual reduction of 2 percent in carbon intensity ,but this was not necessarily because of a shift towards alternative fuels or greater efficiency in using energy. Structural changes in the economy, such as a move towards a service-oriented system, played a big part. The shift was natural as most OECD countries had already completed their industrialisation processes. Decarbonisation rates sustained from 1971-2006 range across the 26 OECD nations ,from a 3.6 percent per year. The unweighted average rate for all 26 OECD nations is 1.5 percent per year, only 16.5 percent faster than long-term global decarbonisation rates (1.3 percent per year).

Many OECD nations also decarbonised by exporting their polluting industries to other countries. Japan had an explicit policy of locating heavily polluting industries in foreign countries. European countries reduced carbon emissions by 6 percent from 1990 to 2008 by exporting production to developing countries. In the same period, European import of embodied carbon from developing countries increased 36 percent. 18 percent of embodied carbon was through exports from China.

In 2022, carbon emissions were 64 percent higher than in 1990, the year the first report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was released and 5.2 percent higher than in 2015 when the Paris Agreement was signed. Even when the economy slowed down dramatically under COVID-19 restrictions, carbon emissions fell by only about 6 percent in 2020 and rebounded quickly after restrictions were lifted.

Current projections of global population size and GDP per person imply that the world must reduce the rate of CO2 emissions per unit of real GDP by around 9 percent per year on average to decline by around 95 percent to reach the climate targets. The rate of decoupling during the next three decades will have to be almost five times greater.

Most of the burden of decoupling has fallen on developing countries like China and India. The methodologies of carbon emission reduction efforts sharing between countries are based on equal marginal abatement costs (to minimise global carbon mitigation costs), which is not only un-equitable and disadvantageous for emerging economies such as India and China with lower historical emission. Between 1990 and 2016, the world achieved an average so-called ‘decoupling rate’ of 1.8 percent per year. Since the 1860s, the global annual average decoupling rate is 1.3 percent per year. For China to achieve peak carbon emission by 2030, a 4.5 percent reduction is required. Achieving a 4 percent per year or greater rate of decarbonisation is unprecedented in recent history.

Decarbonisation policies could have a negative impact on the goal of increasing per person incomes in China and India. In June 2015, Zou Ji, Deputy Director General, National Centre for Climate Change, China, highlighted the importance of the joint announcement from the world's top two economies and emitters, USA and China, and pointed out the significance of China's aim to peak emissions before reaching the income level of USD 20-25,000 per person. In 2022, the per person GDP of China was about USD 12,720 (current USD), and in India it was about USD 2238. Carbon emissions of industrialised countries peaked at per person income levels of well over USD 23,000 – USD 34,000. Though the USA is an outlier with per person CO2 emissions peaking at well over 20 tonnes, countries in western Europe peaked at CO2 levels of about 10-15 tonnes at comparable incomes. To achieve per person GDP of about USD 34,000 by peak year 2030 China will have to grow by an annual average of over 13 percent while its carbon intensity is falling at about 9 percent. For India to achieve emission peak in 2040 with per person GDP of USD 34,000 it will have to have an annual average growth of over 16 percent while substantially reducing its carbon intensity. These trajectories are practically impossible to achieve.

The academic debate on decarbonisation is largely theoretical as it substitutes the need for growth with the need for near impossible decarbonisation rates in developing countries. Developing countries like India and China want to grow and will implement policies for growth. The idea that rich countries will make deep cuts to GDP to achieve decarbonisation, make space for growth of developing countries and support poorer countries with financial aid is also theoretical. Rich countries have to grow and limit financial outflows to service pensions and social security for an ageing population. It is time for the debate on decarbonisation to get real.

Source: Statistical Review of World Energy 2023

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV

.png)

.png)