This article is a part of the essay series: Not the End of the World: World Environment Day 2024

Marking the 30th anniversary of the United Nations (UN) Convention to Combat Desertification, this year’s World Environment Day is focusing on a related key pillar of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030): “Land Restoration, Desertification, and Drought Resilience.” Highlighting the urgent need to address land degradation, restore ecosystems, and build resilience against the impacts of drought and desertification, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations have put together a 10-point strategy, involving stakeholders at various levels, to restore a healthy planet. However, even when a disproportionate number of women from among the 3.2 billion people worldwide and 74 percent of people living in poverty derive their primary livelihoods from agricultural land or its ecosystem services, the strategy of the UN Decade remains silent on the gendered impacts of land degradation or their role in land restoration efforts. This article delves into the importance of integrating a gender-inclusive cost-benefit analysis (CBA) framework to address the unique impacts on and roles of women in these environmental challenges, highlighting the gaps in current strategies that often overlook the gendered dimensions of land restoration efforts.

Where do we stand today?

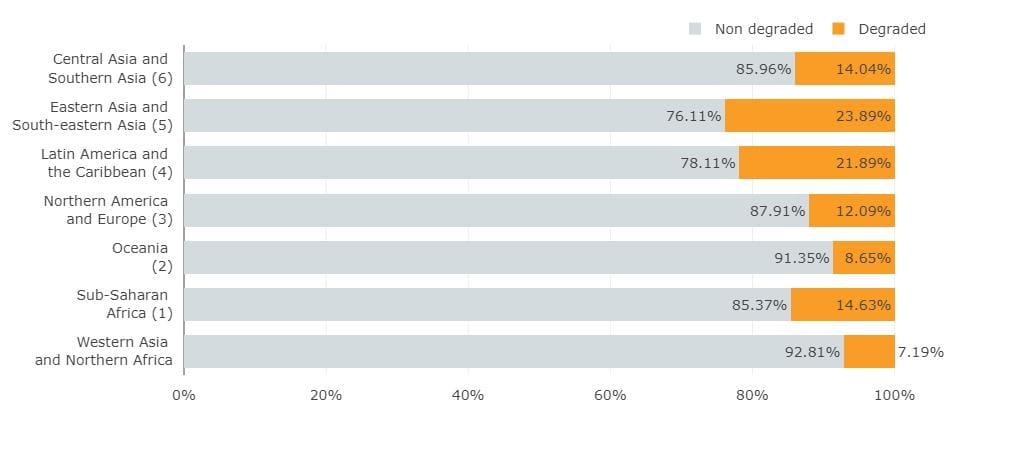

Land degradation is a pressing environmental issue and is increasingly becoming an economic concern. Currently, about 40 percent of the Earth's land has degraded, directly impacting over 50 percent of global GDP. In 2016 alone, the cost of degraded land was estimated to be over US$6.3 trillion annually, with Asia and Africa bearing the brunt of these costs at US$84 billion and US$65 billion per year, respectively.

Land degradation has a direct and profound impact on the livelihoods of half of the global population, particularly indigenous people and women who rely on forests, ecosystem services and agricultural lands. Despite constituting only 5 percent of the global population, indigenous people depend on a significant 22 percent of the world’s land ecosystem. Similarly, in developing countries, approximately 80 percent of the female population is employed in the primary sector, which is directly or indirectly threatened by land degradation. Declining land productivity undermines sustainable development, posing a direct threat to SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 5 (gender equality), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities).

Figure 1: Proportion of Degraded Land across Regions

Source: UNCCD, 2019

Gender dynamics are intricately interwoven into land use and management. Between 2015 and 2020, an estimated 10 million hectares of forests were destroyed annually, impacting approximately 3.2 billion people worldwide, half of whom were women and girls. This is because women, particularly in developing countries, heavily rely on critical natural resources such as land, water, and fuel, and they face the harshest impacts of land degradation due to their extensive engagement in the primary sector or domestic care activities. Women comprise 43 percent of the agricultural workforce globally, yet only 15 percent of these women own their lands. Beyond being denied land ownership, women's decision-making power over their land is limited, as is their access to credit, technology, and other resources. This puts women in a disadvantaged position.

Besides its direct provisioning services, land ecosystems also provide regulating services such as climate regulation, soil health, and pollination; cultural services like recreation and cultural heritage; and supporting services like nutrient and water cycling, which are crucial for maintaining healthy ecosystems. For example, land degradation through extensive deforestation can alter how water moves through an area, leading to increased flooding or drought, or lead to a loss of carbon sinks impacting climate change mitigation. Here again, women remain particularly more vulnerable in these natural disaster-prone settings.

Besides its direct provisioning services, land ecosystems also provide regulating services such as climate regulation, soil health, and pollination; cultural services like recreation and cultural heritage; and supporting services like nutrient and water cycling, which are crucial for maintaining healthy ecosystems.

On the other hand, women are found more likely to adopt climate-smart agricultural practices when they have greater agency and land ownership leading to significant reductions in land-use change. A UN study found that women can increase agricultural yields by 20-30 percent when provided with the same resources as men, reducing the incidence of hunger by 12-17 percent, which again is likely to reduce the deforestation and land use change for agricultural or allied industries expansion. Moreover, the social rate of return for an equivalent increase in women’s income levels, as compared to men, has been found to have a higher multiplier effect. Women reinvest an average of 90 percent of their income on their family’s well-being, particularly in health, education, and nutrition, compared to only 35 percent reinvested by men. The disparate costs and potential benefits associated with women’s land use and management are, therefore, significant and need to be explicitly addressed.

A gender-inclusive approach to land restoration

Land degradation neutrality through land restoration is proposed as the best way to mitigate the damage. At the social and environmental level, land restoration offers multiple benefits, such as alleviating food and water insecurity, mitigating biodiversity loss, and aiding climate change mitigation. In terms of pure economic returns, each dollar invested in land degradation neutrality can generate between US$ 7 and US$ 30 in benefits. Moreover, according to the second edition of the Global Land Outlook report (GLO2), restoring land and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and loss of biodiversity could provide economic benefits worth US$ 125-140 trillion annually. About 80 percent of atmospheric carbon is absorbed back into the soil, so restoring land would help reduce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions levels, which can contribute to overall climate change mitigation. In essence, land restoration offers significant social, environmental, and economic benefits.

Land degradation neutrality through land restoration is proposed as the best way to mitigate the damage. At the social and environmental level, land restoration offers multiple benefits, such as alleviating food and water insecurity, mitigating biodiversity loss, and aiding climate change mitigation.

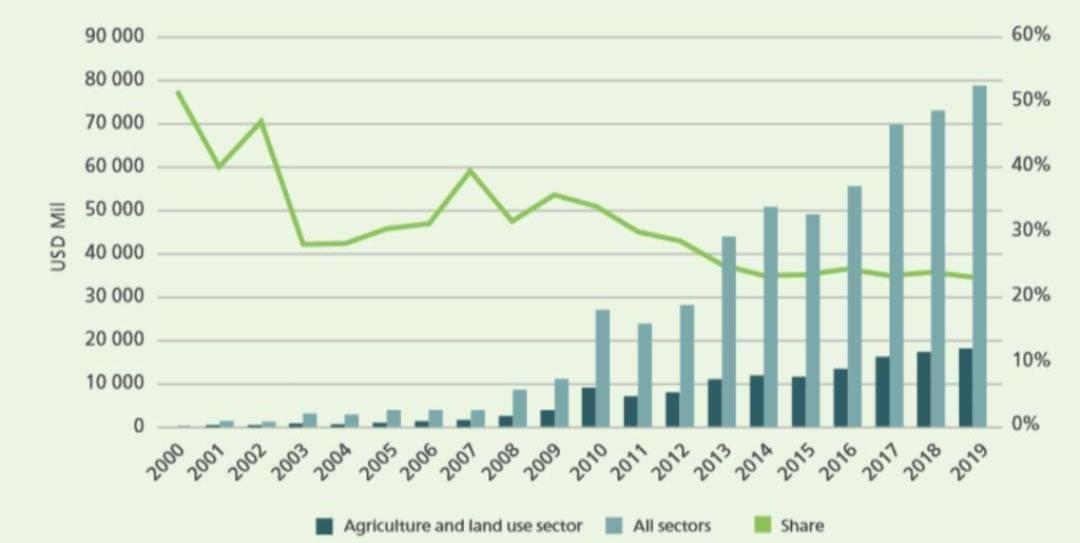

Unfortunately, despite a favourable benefit-cost ratio, funding for landscape restoration is severely lacking, falling short by approximately US$ 300 billion annually. While forests and agricultural land contribute more than 30 percent of the climate solution, they receive just 2.5 percent of all tracked climate finance. Moreover, there was a 20 percent decline in climate finance for land restoration between 2017-18 and 2019-20, with the annual average at US$ 16.3 billion, indicating a massive financing gap.

Figure 2: Climate finance allocations to the agriculture and land use sector

Source: FAO, 2022

A significant challenge with land restoration investments is that environmental and social costs and benefits often lack a market value, making them financially unattractive to private investors. These include the costs and benefits associated with existing gender disparities. Empowering women through land restoration initiatives can not only enhance their productivity but also improve community well-being and development outcomes. Incorporating a gender-inclusive approach to valuing the social rate of return of land restoration policies and activities can introduce significant positive externalities and result in an even more favourable benefit-cost ratio. Moreover, it can show that investing in women within the context of land restoration is both a smart economic strategy and a means to achieve higher social rates of return across generations.

A significant challenge with land restoration investments is that environmental and social costs and benefits often lack a market value, making them financially unattractive to private investors.

A gender-inclusive approach to land degradation neutrality (LDN) should, therefore, focus on:

-

Encouraging alternative forms of investment in land restoration by ensuring that the cost-benefit analyses of these projects include a gender perspective. By recognising and valuing women's unique contributions and needs, investors can make more informed and equitable decisions.

-

Climate finance is pivotal in supporting the transition to low-carbon agriculture and enhancing forest conservation activities. Given the current shortfall, directing climate finance towards agriculture and land-use projects with a gender-responsive focus can serve as a smarter way of yielding better results by addressing existing gender disparities.

-

Securing land tenure rights can grant women access to government schemes, amplify their role in household decision-making, and enable access to credit, further empowering them economically. Therefore, the focus should be on providing women with tailored financial services and credit facilities to support their involvement in sustainable agricultural practices and land restoration projects.

-

Ensuring women have equal access to agricultural inputs, such as seeds, fertilisers, and modern farming technologies, can boost productivity and resilience. Gender-sensitive agricultural extension services should be developed to address the specific needs of women farmers, including training on sustainable land management practices and climate-resilient agriculture.

However, to adopt these strategies, it is crucial to address the gender data gap regarding land degradation impacts and restoration efforts. All data collected on land use, degradation, and restoration efforts must be disaggregated by sex. This is essential for establishing gender-specific targets with respect to land degradation neutrality and generating baselines to understand how different genders are impacted and can contribute to land restoration efforts. Integrating these inferences with other socio-economic indicators for a more holistic approach is also crucial. Closing the gender gaps in the LDN approach through targeted and effective interventions can promote gender equality and sustainable land management.

Sharon Sarah Thawaney is the Executive Assistant to the Director of ORF Kolkata at the Observer Research Foundation.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV

.png)

.png)