-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Jan Aushadhi Kendras have expanded rapidly, covering all Indian districts by 2025. This analysis explores their growth, impact, and regional disparities.

Image Source: Getty

Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP), popularly known as ‘Jan Aushadhi,’ is a scheme that has seen rapid progress under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) governments over the past decade. Every year, 7 March is celebrated as “Jan Aushadhi Diwas,” aiming to enhance public awareness and confidence about generic medicines.

The Jan Aushadhi Scheme—or people’s medicine scheme—was launched in November 2008, responding to the high out-of-pocket medical expenditures. This scheme is one of the very few key health initiatives outside the purview of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Under the scheme, dedicated outlets known as ‘Jan Aushadhi Kendras’ (medicine shops) were opened to provide quality generic medicines at affordable prices. The scheme initially got off to a slow start, and in the first six years of operation, until 2015, only 80 Jan Aushadhi Kendras had been established in selected states. However, the pace of expansion accelerated tremendously in later years.

The scheme had outpaced the government’s deadline, achieving the goal of opening 10,000 Kendras well before the March 2024 target.

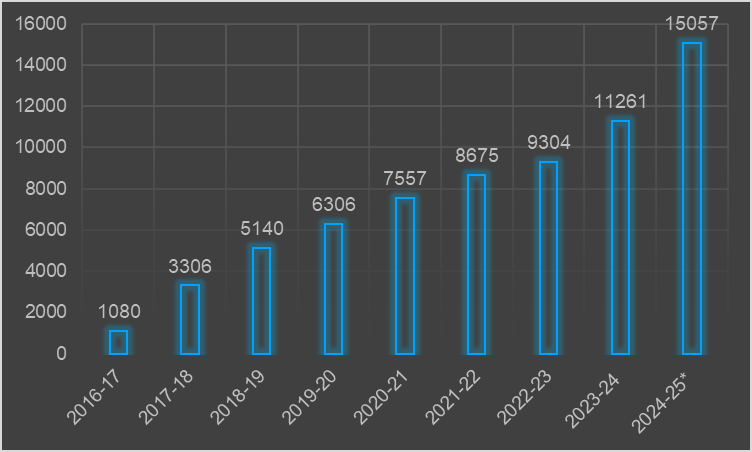

Between 2016 and 2025, around 14,000 new Jan Aushadhi Kendras have been established (Figure 1) across every state and union territory in India. PMBJP has been routinely achieving coverage targets ahead of time. In December 2023, Prime Minister (PM) Modi inaugurated the 10,000th Jan Aushadhi Kendra at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Deoghar. The scheme had outpaced the government’s deadline, achieving the goal of opening 10,000 Kendras well before the March 2024 target. The next target of opening 15,000 Jan Aushadhi Kendras by March 2025 was also achieved, beating the deadline by two months.

Figure 1: PMBJP Kendras across India

* Data till March 2025.

Source: Compiled by the author from GoI’s PMBJP portal and Parliament website.

The context of the high government focus on PMBJP is the high out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPE) in health that push 3 percent to 7 percent of Indian households below the poverty line every year, with studies showing rural and poorer states facing a higher impact. Disadvantaged groups bear a greater financial burden from OOPE in health-related areas, which led to the scheme becoming a policy priority. The government of India assessed that despite India being one of the leading exporters of generic medicines to the world, a major chunk of its citizens lack sufficient access to affordable medication. Ironically, in the Indian market, the branded generic medicines are sold at significantly higher prices than their un-branded generic equivalents, though are identical in their therapeutic value, necessitating government intervention to provide quality generic medicines to the public.

The government of India assessed that despite India being one of the leading exporters of generic medicines to the world, a major chunk of its citizens lack sufficient access to affordable medication.

By the end of January 2025, 15,057 Kendras have been set up with the annual targets for every year being exceeded – a remarkable feat for a government initiative. Currently, every district in India has Jan Aushadhi Kendras. PMBJP has seen steady growth over the years, significantly increasing the number of Jan Aushadhi Kendras. Starting from 1,080 Kendras in 2016–17, the initiative gained momentum with 2,226 new Kendras in 2017–18, bringing the total to 3,306. The growth continued in subsequent years, with the number of Kendras surpassing 5,000 in 2018–19 and reaching 7,557 by 2020–21 (Figure 1). While the expansion rate slowed between 2021–22 and 2022–23 during the pandemic, there was a renewed push in 2023–24, with 1,957 new Kendras, taking the total to 11,261. The most significant expansion occurred in 2024–25, with a record 3,796 new kendras, bringing the cumulative count to 15,057, underscoring the government's commitment to increasing access to affordable medicines across the country, despite apprehensions from segments of the pharmaceutical industry as PMBJP eats directly into the profit margins of branded and branded generic medication.

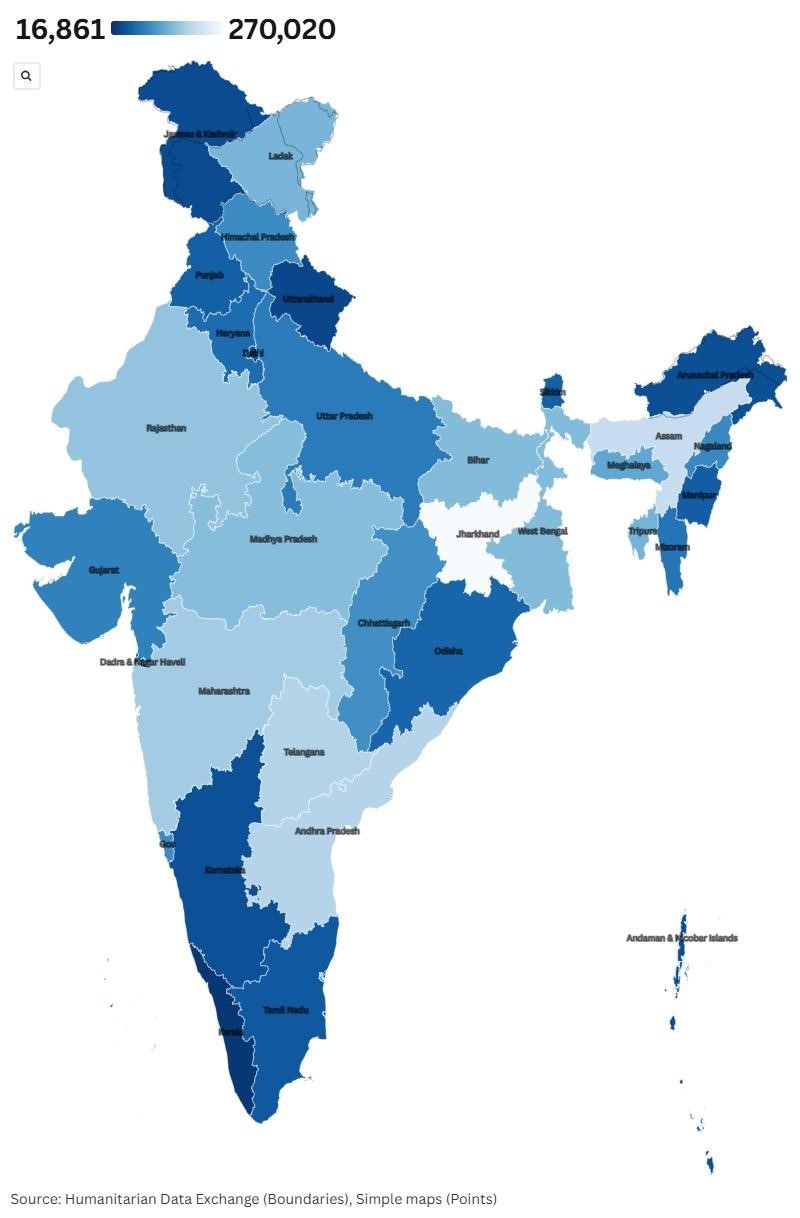

Given the above context and the rapid expansion of the Kendras across India, this article attempts to update an earlier analysis done in 2020 by Brookings India–perhaps the only one looking at the state and district-level spread of the Jan Aushadhi Kendras. The study found that districts without Jan Aushadhi Kendras were concentrated mostly in the northeast and central India. It also found that the population per Jan Aushadhi Kendra is relatively lower in the southern states of India. It identified the public perception of generic drugs being of inferior quality as a binding constraint for the scheme’s expansion. This is despite studies from the early days finding no quality difference between Jan Aushadhi medicines and their branded counterparts. Drug shortages at the Kendras were also identified as a major bottleneck. Compared to 2020, when many districts lacked sufficient Kendras, all Indian districts are covered as of 2025. Average population covered by Jan Aushadhi Kendras at the India level has come under 100,000 for the first time in 2025, with 92,964 people covered per kendra. In 2020, only five states, namely Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh, had more than 500 Jan Aushadhi Kendras. Now, ten states have more than 500 Kendras. However, population coverage varies widely across states (Figure 2), from 16,861 in Kerala to 270,020 in Jharkhand. It needs to be noted that some states have their parallel free/generic medicine distribution networks, like Mukhyamantri Nishulk Dava Yojna in Rajasthan, Jana Jeevani in Telangana, Niramaya in Odisha, and Karunya/Neethi in Kerala, which are not accounted for in the calculations.

Figure 2: Average population covered by Jan Aushadhi Kendras in Indian states (2025)

Source: Data compiled by the author from PMBJP (no. of outlets) and UIDAI (projected 2024 population), visualised using Flourish

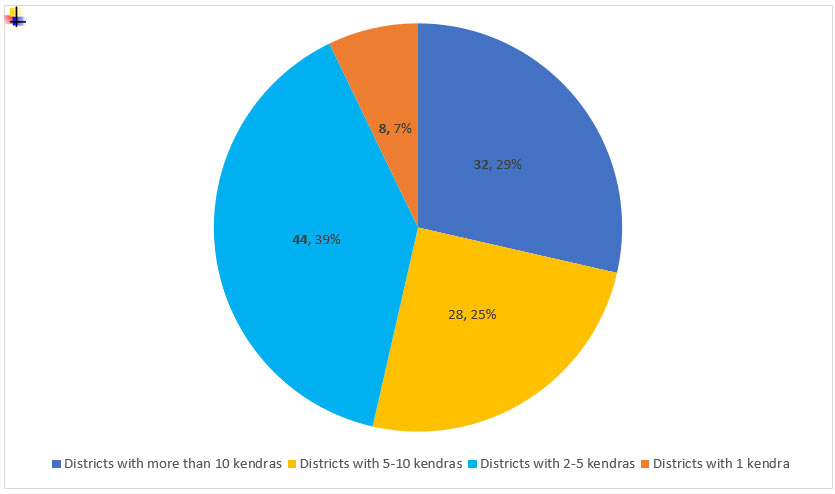

The Brookings India study noted that districts with no Jan Aushadhi Kendras were concentrated in rural, less-developed areas. Therefore, it will be good to look at the current status of the distribution of Kendras in the least developed districts of the country. The Aspirational Districts Programme (ADP), launched by NITI Aayog in 2018, aims to accelerate development in 112 underdeveloped districts across India. These districts were selected based on low performance in key socio-economic indicators such as health, education, agriculture, financial inclusion, and infrastructure. Analysis of the latest PMBJP data shows that 60 aspirational districts have more than 10 Kendras, and just eight (7 percent) have a single kendra (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of Jan Aushadhi Kendras in Aspirational Districts (2025)

Source: Data compiled by the author from PMBJP (no. of outlets)

Compared with the 653 more developed districts in India (Figure 4), the proportion of districts with more than 10 Jan Aushadhi Kendras is understandably much higher, as earlier studies have shown that stores are more likely to be opened in more developed areas. However, somewhat counterintuitively, the proportion of districts with a single Kendra is higher in the more developed districts (9 percent) than in the aspirational districts (7 percent). This suggests that the incentives put in place by PMBJP to attract the establishment of Kendras in lesser-developed areas have started to work.

Figure 4: Number of Jan Aushadhi Kendras in other districts (2025)

Source: Data compiled by the author from PMBJP (no. of outlets)

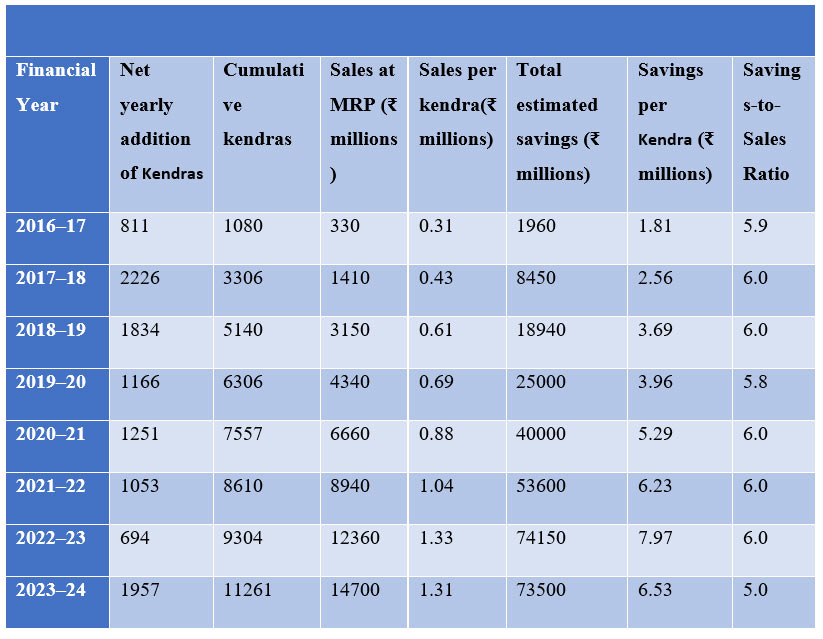

It is a fact that, out of the 1.5 lakh crores rupees worth of annual sales of medicines in India, the sales of Jan Aushadhi Kendras at around INR 1500 crore remains small. However, over the last decade, it has expanded from a mere INR 33 crore to about INR1500 crore rupees and shows tremendous potential for further growth. Moreover, given the considerably lower price of the medicines, the Kendras cause savings that are many times the monetary value of sales. Table 1 shows that, on average, every rupee spent at a Jan Aushadhi shop leads to around six rupees of savings for the household. Over the years, PMBJP has played a role, along with initiatives like PMJAY, to bring down spending in India, from 64.2 percent in 2013-14 to 39.4 percent in 2021-22. The decline is expected to continue as these schemes mature in the future.

Table 1: Financial impact of PMBJP over the years

Source: Data compiled by the author from the Annual Report, Dept of Pharmaceuticals, GoI

A parliamentary committee report in 2021 stated that stockouts caused by hurdles in the timely procurement of medicines due to the failure of suppliers have been a major constraint. Around 90 percent suppliers of PMBJP used to be from MSME Sector who struggled to absorb the fluctuations in price of raw materials, and defaults in supply in times of stress. Remedial measures have been taken, and most of the large Indian companies that dominate the global generics market are now supplying to Jan Aushadhi Kendras through a strong and expanding network of warehouses and distributors.

Medicines for PMBJP are procured only from World Health Organization–Good Manufacturing Practices (WHO-GMP) certified suppliers, and each batch of drugs is tested at laboratories accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) before they are sent to the Kendras. While things improve on the regulatory front, there is a lingering constraint of perception among the doctors and the general public about the quality of generic medicines. In the Indian market, a higher price is often mistaken as a proxy for higher quality. Focused high-profile campaigns are being conducted to remedy the situation, as average sales per Kendra have grown four times over the last decade (Table 1) in parallel with a rapid expansion of Kendras.

In parallel to efforts to improve the public perception of the quality of generic medicines, India needs to accelerate the process of strengthening the drug regulatory system and align it to internationally accepted standards.

There is an urgent need to expand the number of Jan Aushadhi Kendras in the 71 districts–many less developed, far-to-reach, border, arid, tribal, or districts with a history of political violence and insurgency. In parallel to efforts to improve the public perception of the quality of generic medicines, India needs to accelerate the process of strengthening the drug regulatory system and align it to internationally accepted standards. Lastly, a zero-tolerance policy towards fake medicines and other pharmaceutical crimes needs to be adopted, as public trust in the system is built on years of citizen experience, and strong action is required to undo the impact of decades of a weak regulatory ecosystem within the pharmaceutical sector.

Oommen C. Kurian is a Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation.

The author acknowledges Manshi, an intern with ORF, for helping compile PMBJP data

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +