.png)

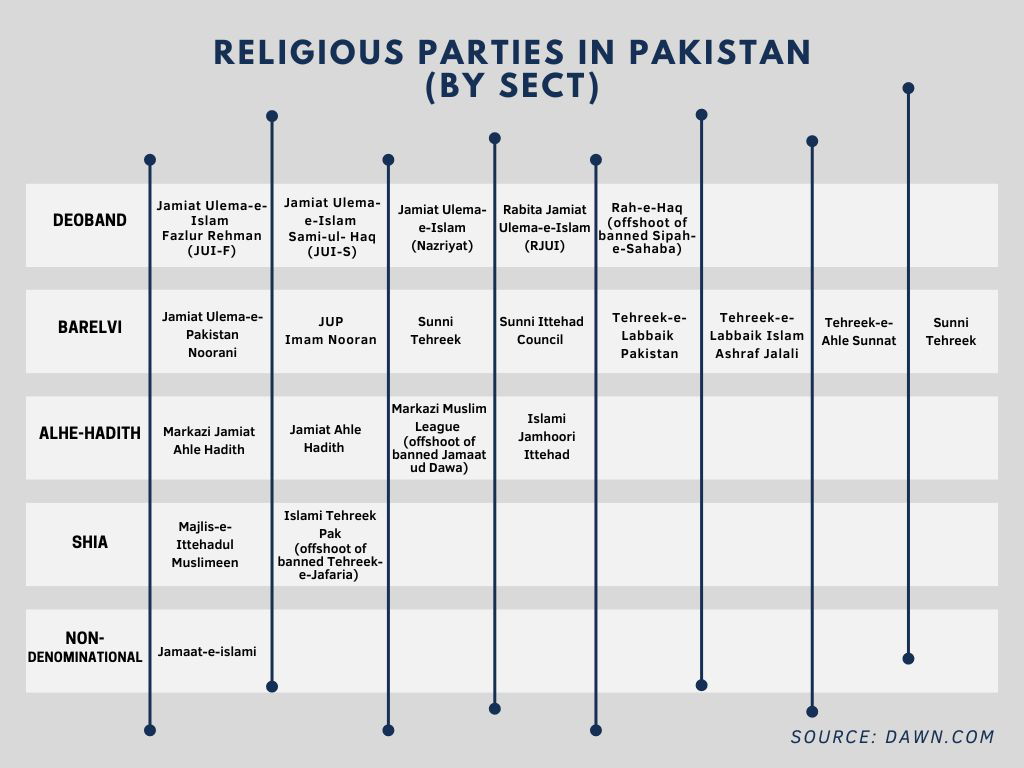

The February 2024 general elections in Pakistan witnessed a notable surge in the participation of religio-political parties, with 23 (refer to Fig. 1) out of the 175 registered parties identifying as such, compared to only 12 in 2018. However, this increment doesn't necessarily translate into electoral success, as the vote share of many sectarian parties, especially smaller ones, has been consistently declining since 2013.

In Pakistan, the military establishment, often referred to as the ‘deep state’, has played a crucial role in shaping who takes control of the government.

In Pakistan, the military establishment, often referred to as the ‘deep state’, has played a crucial role in shaping who takes control of the government. Without its patronage, securing a strong mandate on the ballot is not enough to seize the reins. Although political parties devised a strategy to harness the ‘electables’ to bolster their prospects, leadership from sectarian parties, despite their roots in the ‘biradari system’ and ties with the military, has failed to climb to the highest echelons of the government.

Fig. 1: Religious parties in Pakistan and their sectarian affiliations.

Source: Dawn

Debilitating performance in 2024 elections

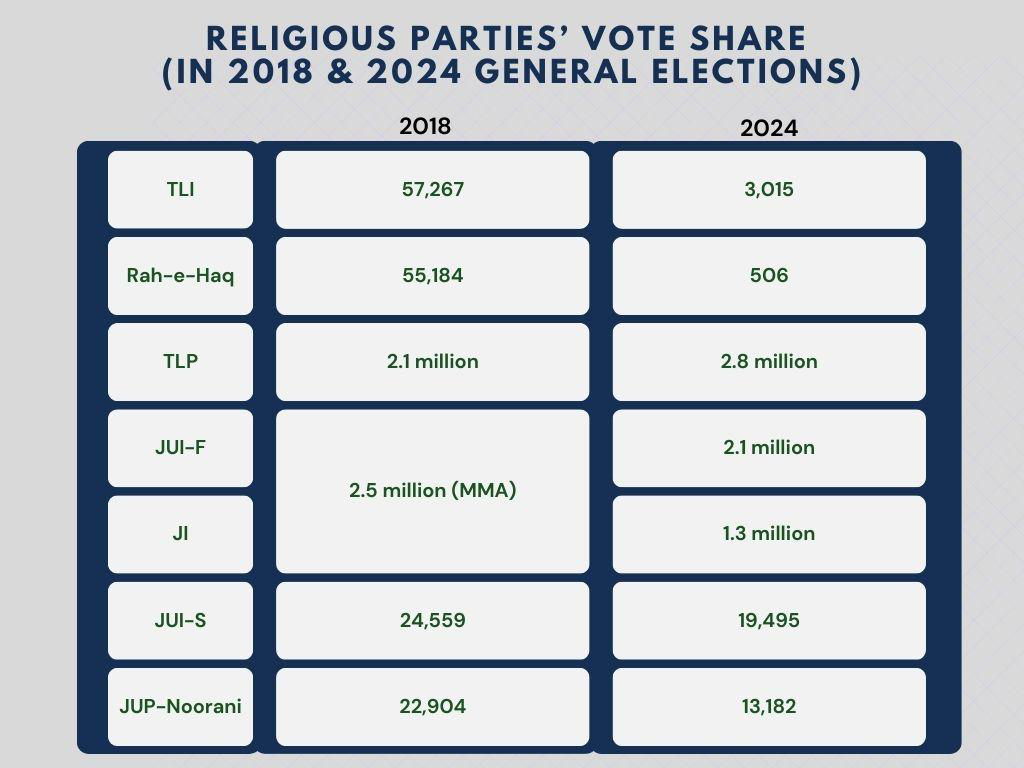

The performance of religious parties peaked in 2002 when the six-party conglomerate Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA) became the third-largest political force in the country. This coalition had evolved in response to General Musharraf’s crackdown on religious militant organisations to project cooperation to the US’ “War on Terror” policy and its political underpinnings in Afghanistan. In 2018, some semblance of religious parties gaining electoral traction was observed, however, this year, their entanglement in the crossfire of pro and anti-establishment mood within Pakistan minimalised their electoral impact (refer to Fig. 2). They could only garner about 12 percent of the votes nationwide, a significant decline from their combined vote share doubling to 10 percent in 2018 from just 5 percent in 2013. This is despite, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) fielding the second and third most number of candidates respectively, superseding two of the prominent mainstream parties—the PPP and PML-N.

Fig. 2: Comparison between the vote share of Religio-political parties in 2018 and 2024 General Elections in Pakistan.

Source: Gallup Pakistan

2018 also marked the year for the electoral debut of Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) , a Barelvi-ultra right party. It emerged as the fifth-largest party, sparking speculations about its alleged military backing to degenerate Nawaz Sharif’s party by invoking the finality of prophethood. As seen in 2018, in 2024, its overall vote share remained stagnant despite joining hands with Sunni Tehreek (ST)—a Barelvi party that accuses India of sponsoring Deobandi Jihadi leaders. Parties like Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) failed to win a single seat in the national assembly; its emir—Sairajul Haq, as a result, opted for abdication.

Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) clinching only three National Assembly seats evokes unfulfilled memories of the 1997 elections where the Taliban’s inroads in Afghanistan were expected to influence Pakistan’s political landscape, triggering the establishment of a conservative government, especially in Balochistan.

Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) clinching only three National Assembly seats evokes unfulfilled memories of the 1997 elections where the Taliban’s inroads in Afghanistan were expected to influence Pakistan’s political landscape, triggering the establishment of a conservative government, especially in Balochistan. However, its supremo—Maulana Fazlur Rehman who exploited his friendship with the regime to strike a deal with Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) to avoid disrupting Pakistani elections, managed to secure a National Assembly seat from the Baloch border district of Pishin. Conceding to the JUI-F’s populist credentials and progressive coalition history which earned it the moniker ‘da thekeydaro dalaa’ (the party of contractors) due to active alignments with left and liberal parties in the past and the anti-government alliances like the People's Democratic Movement (PDM) in the present, its performance in Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) was purportedly disappointing. Moreover, the established parties' internal faltering allowed its Deobandi madrassah network to blend with Sindhi nationalism, saving its face in Sindh.

Deconstructing the pursuit of mainstream appeal

Upending tradition, the religious parties, this time around, appeared to manoeuvre towards the mainstream politics. This repositioning is evidenced by attempts to shed their conservative image by focusing on women's rights, a key concern for a significant portion of the electorate. Upon closer scrutiny of their commitments, particularly regarding gender-based segregation of schools, desks, and public transportation, amongst others, it became apparent that such promises are merely tokenistic. Creating safe spaces for women is crucial, but ‘segregation’ can quickly become ‘seclusion,’ hindering assimilation and reinforcing gender stereotypes. This pattern extends to social media usage too, in Pakistan. Gendered segregation of polling booths into binary (male and female) was even a factor behind the gender discrimination encountered by transgender community in exercising their electoral right in the February polls, precluding their access to the electoral process.

Riding on the back of ‘Islam, Pakistan aur Awam’ the TLP tried to project itself as a mainstream political party by undertaking an inclusive manifesto, although the terminology remained vague. In 2023, it ran a three-week-long march to protest against the sudden surge in petrol prices and inflation. The party also mobilised women and fielded women candidates for general seats this time and vowed for the establishment of a special institution to protect women's rights, ensuring their legal and Sharia rights in inheritance and other matters.

Jamaat-e-Islami, the first party to announce its manifesto back in 2023 promised women rights as enshrined in the Quran and Hadith. The manifesto read: “Immediate steps will be taken to give women the share of property from her father or husband’s property, to provide a safe working environment delineating age relaxation for widows and divorced women in government jobs and maternity & child rearing leaves”. It announced legal measures to financially empower women by promoting yellow industries. Its core claim revolved around reforming legal frameworks to address issues like dowry and honour killings and other significant roadblocks to women's full rights in society.

The manifesto also stressed over barring candidates who do not give their female family members their due inheritance from contesting in elections as well as from travelling abroad—quite a radical stance. All in all, the proposal to establish family institutes for the stability and protection of the family system aligning with the traditional values takes us back to square one since a traditional family system operates on unequal power dynamics, gendered division of labour and propagation of violence against women. It also misaligns with an inclusive understanding of the family system, acknowledging extended and single families in its definition, that these parties claimed to espouse.

The manifesto also stressed over barring candidates who do not give their female family members their due inheritance from contesting in elections as well as from travelling abroad—quite a radical stance.

Religious parties' obsessive mainstream signalling underpins their overemphasis on optics, which is likely to hamper their long-term political legitimacy. The TLP's vote-grabbing strategy in Punjab and Sindh fractured the Barelvi parties’ base, weakening their bargaining power with established parties. In the process, they also confuse and alienate their existing voter base, take for example the TLP’s initial claim to fame was capturing the conservative flank of mainstream parties, while for JUI-F, it was old-school Islamism (Sharia imposition). Their serious attempts at mainstream appropriation through post-Islamist politics (democratic values) can potentially eat a significant portion of their voter pie, which is conservative.

Similarly, their harboured ideological constraints shall resist political expediency, exemplified by the instance of their inability to co-opt the transgenders—a demographic counted within the gender minorities term and which finds its mention in the manifestos of PPP, PML-N, PTI and ANP.

Chasing mainstream dreams, facing sectarian realities

It is not to say that Islamic politics is the monopoly of sectarian parties alone. No matter the eyewash, mainstream parties of the likes of PTI, PPP and PML-N conveniently reiterate their Islamic credentials. The PTI declares its aim to follow a welfare state model embracing Islamic socialism and ‘Medina’ like welfarism while advocating against Islamophobia in international forums. PML-N has been quick to hold PTI’s holy claims accountable by a religious yardstick. Furthermore, these parties readily exploit the sectarian parties to satisfy their electoral interests. Ahead of the polls, the PPP allied with JUI-F in Balochistan despite being at loggerheads with it in Sindh. While the PTI in its bid to legitimise the reserved candidates used the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC), a party that avoided the electoral contest initially.

Historically, Islamist parties’ performance has been better when tied to a coalition similar to the MMA. However, sectarian feuds arising out of a three-way Sunni Islamist turf war within Pakistan, characterised by radical Barelvism rivalling the Deobandi and Wahabi schools of thought are compelling parties to prioritise individual gains. Thus, many parties risked clashing against each other in their strongholds, like the JI and JUI-F in KP and Balochistan. Considering the scattered vote bank of religious parties, the tactic proved to be counter-productive.

By and large, the stunting of any religious dark horse in Pakistan’s elections is positive news for India, for these destabilising forces have origins in anti-India militancy and maintain close ties with the deep state, TTP, ISKP, and the Taliban. Notably, parties like JI ran their campaign on the rhetoric of independence for Palestine and Kashmir while TTP recently called for defeated Islamist parties to unite for an ‘Afghan Taliban-inspired’ order.

Their immense grassroots strength, stemming from social activist origins, often blurs the rural-urban voting divide. Post-poll analysis shows that TLP has a past of resonating with the young, tech-savvy, educated, lower-middle-class demographic and in Karachi’s local body elections JI trailed the mainstream PPP by seven seats. Considering the surge in young voters (now comprising 45 percent of the electorate), the scope of their presence is unlimited, given they utilise it efficiently, unlike this time. For now, their electoral marginalisation is likely to curtail their capacity to serve as influential pressure groups pouring fundamentalism into policies in crisis-prone Pakistan, where rational faculties are already compromised by the ‘hybridity’ and economic distress, easing security concerns for India.

Vaishali Jaipal is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

.png)

PREV

PREV

.png)

.png)