-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Have falling tariffs been a quiet catalyst for growth across emerging markets? If so, it serves as a call to revisit the growth trajectories and strategies.

Image Source: Getty

The international trade landscape has received a jolt from the Trump administration’s aggressive push for reciprocal tariffs. This not only signals a deeper retreat into economic insularity but is also symptomatic of a threat to global growth. This pivot by the world’s largest economy—once hailed as the biggest proponent of the laissez-faire system in international trade and finance—marks a dramatic departure from the liberalising tide of the past. In many ways, Trumpism, today, has become a metaphor for a world grappling with the tremors of resurgent protectionism. This inward turn in US trade policy and the reactionary measures by the second largest economy, China, have prompted a closer look at how emerging economies, in contrast, have navigated the liberalisation path over the same period. Against this backdrop, this article puts forth three core propositions: (a) since 2000, emerging economies have cut tariff rates more aggressively than advanced nations, with India leading the way, closely followed by China; (b) tariff levels in emerging markets are showing signs of convergence; (c) tariff liberalisation in India has spurred consumption, and may have laid the groundwork for a shift toward consumption-driven growth.

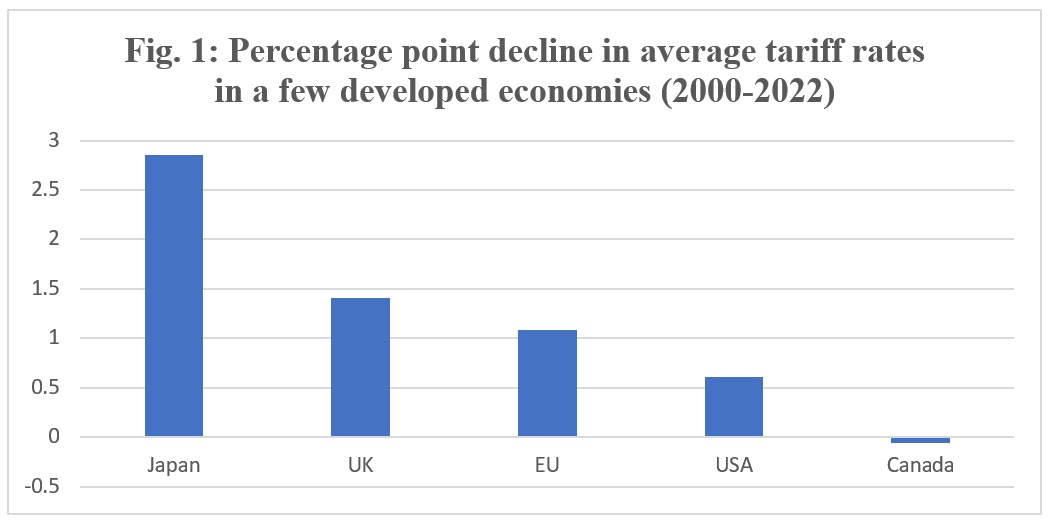

As such, many economies of the developed world that already exhibited a low tariff regime began reassessing their commitment to unfettered free trade ever since the 2008 financial crisis. Europe, while maintaining lower average tariffs, increasingly employed non-tariff measures (NTMs) such as stringent environmental and safety standards, the latest example being the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Japan has maintained a stable tariff structure (1.8 percent average), with low tariffs for industrial goods, while some protection remains in agriculture. The non-trade measures (NTMs) are used mainly for safety and food standards but are not aggressively protectionist. In effect, Japan is largely liberal, with moderate use of NTMs. Rather, given the low average tariff rates in most of the advanced economies varying between 1 and 4 percent, there was not much scope for quantitative tariff reduction over the last two decades, with percentage point declines in average tariffs being below 3 percent (Fig. 1).

Source: Computed by Author from World Bank data

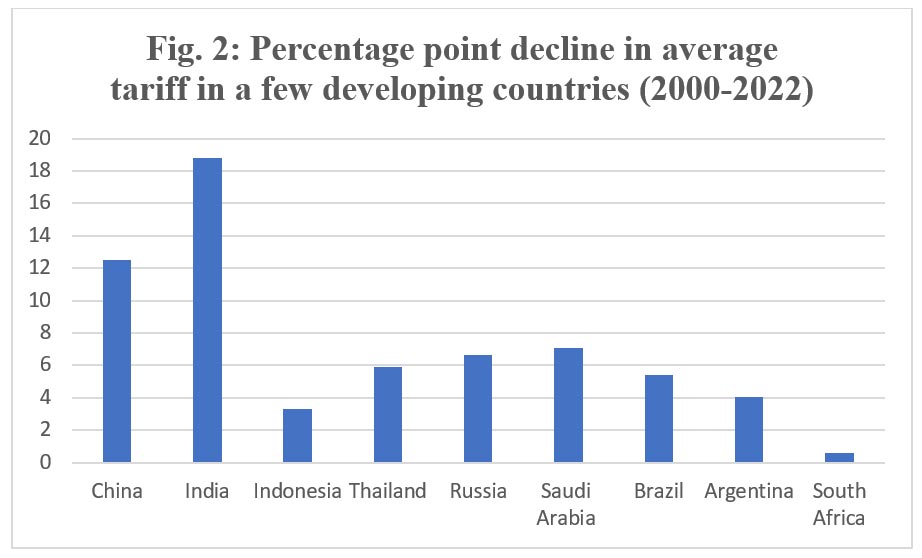

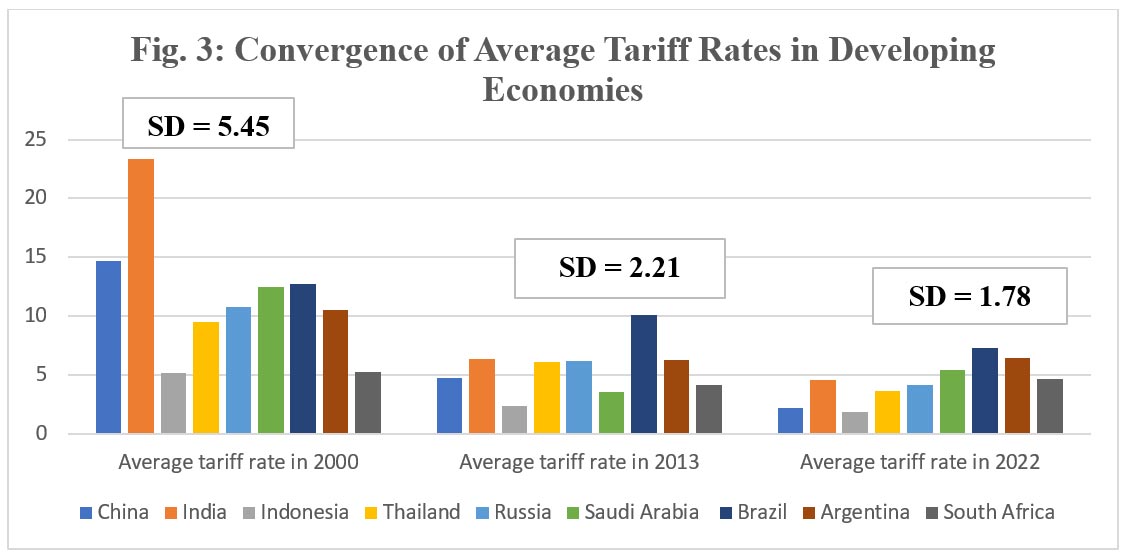

A comparative snapshot reveals that developing economies have outpaced their advanced counterparts in slashing tariffs (Fig. 2), while the declining standard deviation (SD) of average tariff rates (Fig. 3) of the developing economies overtime points to convergence in trade openness for these countries in terms of tariff rates. India leads the pack with the highest percentage point decline in average tariff rates from 2000. The Indian average tariff rate is around 4.6% in 2022- almost a 19-percentage-point decline from 23.4% in 2000. This is closely followed by China, whose average tariff has seen a sharp decline from around 15 percent in 2000 to 2.5 percent by 2020. It also reduced MFN tariffs during the US trade war to diversify sources. However, China heavily uses subsidies, and local content rules and provides state-owned enterprise support. While Russian tariffs dropped from 8.6 percent in 2008 to 3.1 percent in 2015, post-2014 sanctions led to import bans, localization mandates, and export controls. This caused Russia to become more protectionist, driven by geopolitics and security policy.

Source: Computed by Author from World Bank data

Both Brazil and South Africa also reveal a substantial decline in tariffs over the years. However, Brazil levies a tariff that is still high relative to peers and frequently uses para-tariffs and local content rules. South Africa is involved in increasing the use of safeguards and trade remedies, especially in steel and agriculture. However, India makes it evident that a blanket approach to either liberalisation or protectionism may not be effective. Instead, a strategic mix that protects critical domestic industries while promoting competitiveness and integration into global markets can be more beneficial.

Source: Computed by Author from World Bank data

Further, as one can make out from Table 1, with the steady decline in tariffs in the developing world, the rates are approaching those of the Global North economies, though still a bit far.

Table 1: Declining Average Rates of Tariff

| Year | Average Tariff Rate in the Select Developing Nations | Average Tariff Rate in the Select Global North Nations |

| 2000 | 11.71 | 2.54 |

| 2013 | 5.05 | 1.46 |

| 2022 | 4.51 | 1.37 |

Source: Computed by Author from World Bank data

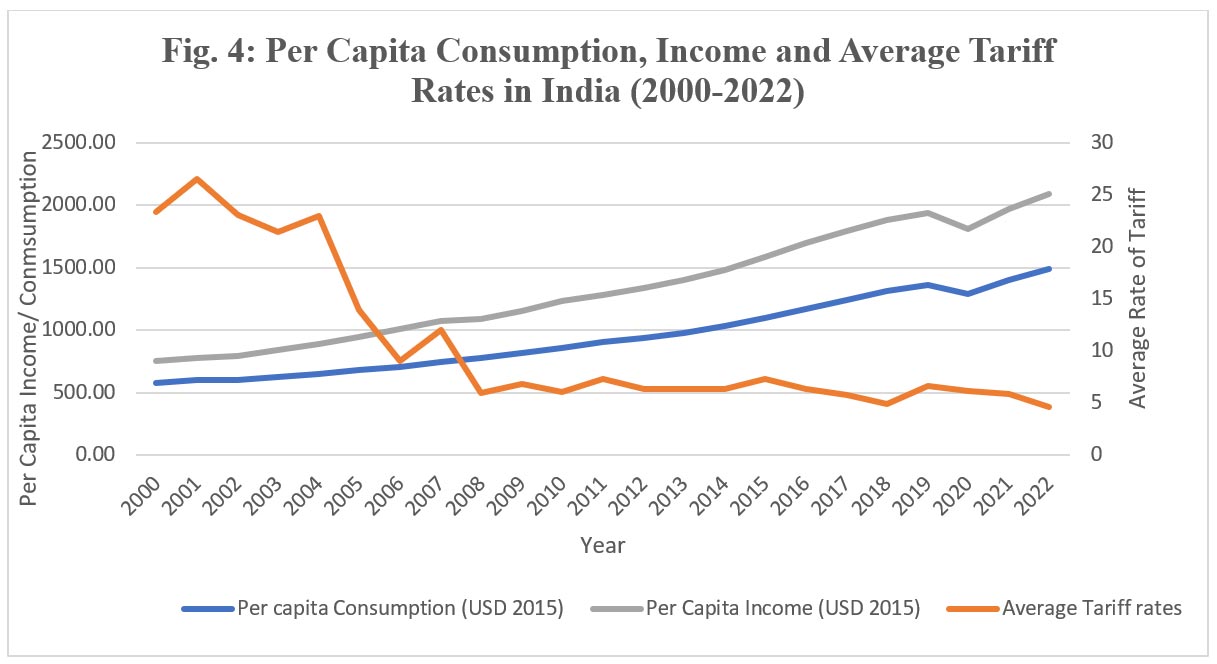

A closer look into the impacts of tariff liberalisation on the Indian economy shows some interesting results. Fig. 4 shows that while average tariff rates have declined in India, there has been a concomitant increase in consumption. An econometric analysis with per capita consumption as the dependent variable and average tariff rates as an explanatory variable (along with per capita income) provides indicative evidence that the declining average rates of tariff have led to an increase in per capita consumption over the years. India, therefore, emerges as a balanced reformer with substantial tariff reduction, high trade openness growth (with its trade-GDP ratio increasing by 85 percent during this period), and per capita consumption rise.

In this context, it needs to be highlighted that despite leading the pack of the emerging economies in terms of reducing the average tariff rates over the past two decades, India did not follow the trajectory of an unbridled tariff liberalisation. Rather, the post-2014 shift marked a recalibrated approach: under the “Make in India” banner, the country moved toward selective protection—raising tariffs on electronics, appliances, and auto parts from 2017 onwards. The weighted average tariff nudged up from 5.8 percent in 2017 to 6.6 percent in 2019, signalling a tactical pause. Yet, this was no blanket protectionism. India became one of the most active users of anti-dumping measures—with 133 active cases in 2023 covering over 400 products—and expanded the mandatory BIS certification regime across categories like toys, chemicals, and electronics. At the same time, tariffs on critical inputs and intermediates were slashed—notably for EVs, semiconductors, and key chemicals—to ease manufacturing bottlenecks and integrate into global value chains. This dual play of shielding sunrise sectors while opening up strategic value chains defines India’s model of “calibrated liberalisation.”

But the real question lies deeper. India’s growth story has been largely driven by consumption ever since 1991, while this article points to a compelling link: tariff liberalisation seems to have boosted per capita consumption by making imports cheaper and more accessible. China appears to have followed a similar trajectory. This sets the stage for a broader, testable hypothesis: Have falling tariffs been a quiet catalyst for growth across emerging markets? If so, this isn’t just an India-specific insight for driving Viksit Bharat; it’s a call to revisit the growth trajectories and strategies of other liberalising emerging economies as well.

Nilanjan Ghosh is a Director at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), India, where he leads the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) and ORF’s Kolkata Centre.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Nilanjan Ghosh is Vice President – Development Studies at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in India, and is also in charge of the Foundation’s ...

Read More +