The Cybersecurity Index (CSI) that the European Union (EU) released in March 2024 is perhaps the first of its kind on an international scale. The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, ENISA, has recently published its design of a composite index to aid the member states of the EU in achieving a high common level of cybersecurity. With the global focus increasingly shifting to matters regarding cybersecurity, the index is a crucial step in evaluating the current standard of affairs and identifying areas that require improvement.

The CSI and its approach towards cybersecurity

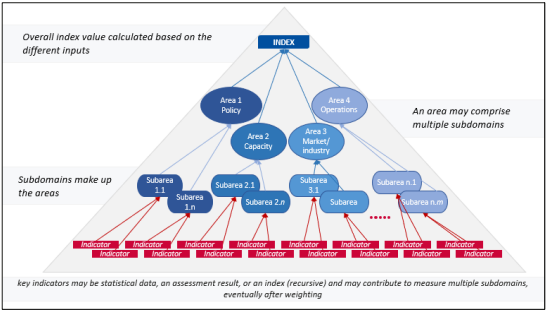

The EU CSI is a hierarchical index that brings together four broad areas of cybersecurity, namely policy, capacity, market/industry, and operations. Each area is treated as a composite variable and is further divided into 16 sub-areas which are then further composed of indicators, many of which are indices that are composite values themselves.

Fig.1 The composite hierarchical framework of the EU Cybersecurity Index

Source: EU Cybersecurity Index Framework and Methodology Note, March 2024

This framework is indicative of a reactive approach towards cybersecurity. The ENISA has yet to put forward a conclusive definition for cybersecurity and has released a document stating that the term does not require one in the conventional. The document proposes a context-dependent definition of cybersecurity, prioritising flexibility. This aligns with the CSI framework, which assesses cybersecurity risk by considering the likelihood of cyber threats, their potential impact, and existing system preparedness. The Cybersecurity Index effectively calculates the ability of a member state of the EU to identify, contain and pacify a cyber-threat.

However, as a metric designed, tested, and proven to function in the European context, this approach and execution fall short when it comes to effectively evaluating the rest of the world. In contexts where the proposed design does not fit like a glove, the index could provide an unbalanced and non-representative result due to the failure to account for three aspects. These are the role of policies in connecting citizens to cyberspace, the preferred presence of an umbrella organisation, and the overall state of IT infrastructure in a nation. Additionally, the lack of transparency regarding the weighting system within the index introduces further ambiguity in its results.

However, as a metric designed, tested, and proven to function in the European context, this approach and execution fall short when it comes to effectively evaluating the rest of the world. In contexts where the proposed design does not fit like a glove, the index could provide an unbalanced and non-representative result due to the failure to account for three aspects.

Shortcomings of the framework

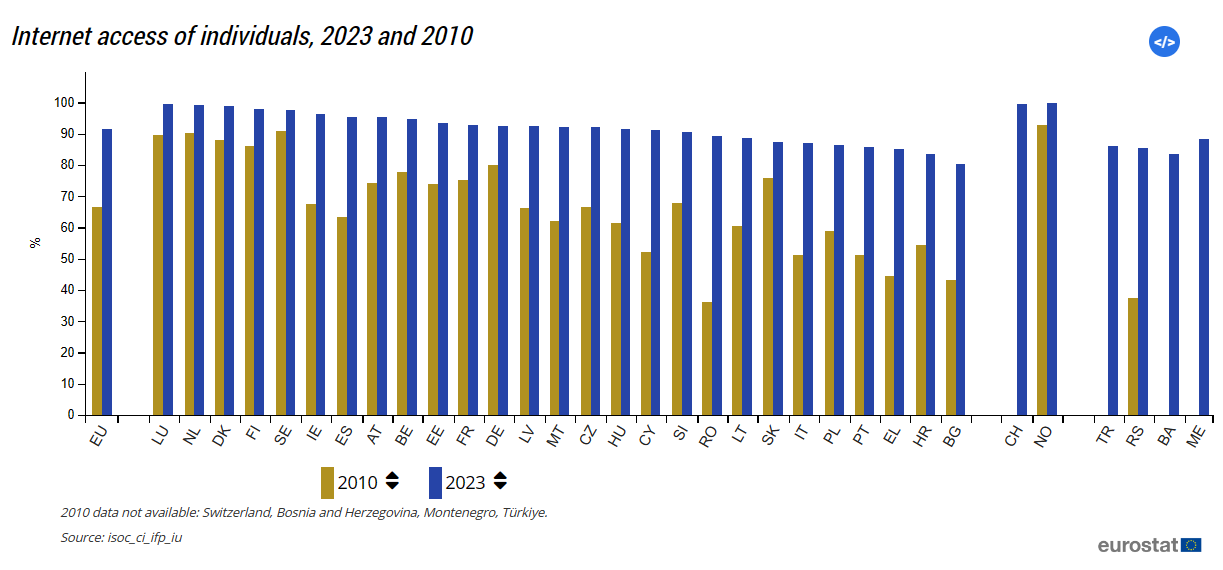

A country's Internet Penetration Rate is the percentage of the population with internet access. As of 2023, the EU Member State with the lowest internet penetration rate was Belgium where 80.4 percent of the population had access to the internet.

Fig.2 Internet access of individuals in the Member States of the EU in 2010 and 2023

Source: Eurostat, 2023

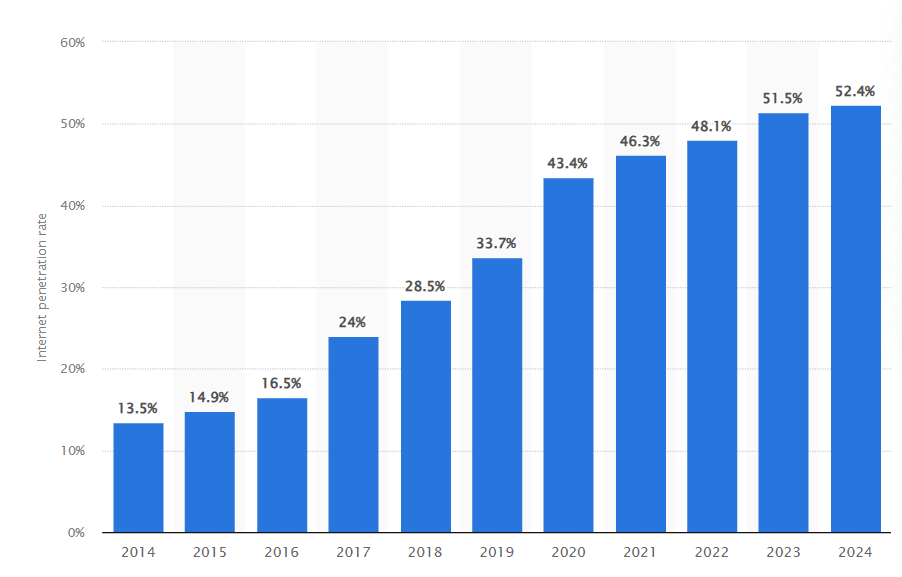

On the other hand, despite the steady rise in the number of internet users in India, the internet penetration rate in India still lingers close to 50 percent as of early 2024.

Fig.3 Internet Penetration rate in India, 2014-2023

Source: Statista, 2024

This does not, however, show that the section of the population without direct internet access is completely disconnected from cyberspace. In the case of India, limited internet access has affected 53.7 percent of Indians. In 2021 government programmes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana and expanded bank services in post offices successfully boosted bank account ownership to 78 percent. This shows that government policy plays a leading role in connecting citizens to cyberspace, despite the policy not focusing on information technology. This effect of the policy is irrelevant in the European context due to high internet penetration rates and is not accounted for in the framework of the CSI. This affects the evaluation of cyber hygiene too, as the percentages of the population mentioned as part of the indicators are unlikely to have addressed this section.

This does not, however, show that the section of the population without direct internet access is completely disconnected from cyberspace. In the case of India, limited internet access has affected 53.7 percent of Indians.

The CSI hinges on the existence of a strong umbrella organisation to facilitate a stream of standardised datasets of the entities being evaluated. All data sources cited by the ENISA except for Shodan are bodies affiliated with the EU, ensuring a sort of uniformity to the data received from various channels, and the index is designed to work in this controlled environment. While this implies that the CSI can be adapted by bodies like the G20, a private party attempting to emulate the index is likely to be impeded by this lack of channels that can provide coherent and uniform data.

No indicators in the design of the CSI deal with evaluating the overall IT infrastructure of the member state, a factor that determines the baseline for cybersecurity a nation needs at that point. The member states of the EU are all well-developed and possess a solid foundation of IT infrastructure and thus, a completely comparative index suffices in the context. This cannot be set as the expected norm for the rest of the globe. The degree of cybersecurity that independent states require is different and is directly related to the state of IT in the nation. Countries with budding IT infrastructure are also less likely to have an established differentiation between policy and legislation regarding cybersecurity as preferred by the CSI according to its framework.

The ambiguity in aggregation weights

The aforementioned issues can be solved by accounting for these issues using a standardised set of parameters while calculating the weights used for aggregation. An efficient index must ensure that all entities being rated are evaluated across an even set of parameters, including coherency in the calculation of weights. However, the framework and methodology note published by the ENISA does not detail the process of calculating the weights used for aggregation at the indicator and area levels. The note merely states that these weights are assigned after assessing the situation in each member state. While this could be beneficial in accounting for varying national contexts and circumstances such as the economic behaviour of establishments and cultural interference, this brings to question the level of standardisation involved in the index. For the CSI to be successfully recreated at a global level, the calculation process behind the weights used for aggregation must be scrutinised in detail.

To elucidate, let us consider adapting the index to the G20 nations. Between India and the Republic of Korea, a significant amount of standardisation is required to ensure that the cybersecurity of these nations is compared fairly. The Republic of Korea has an economic environment that ties down most of its cybersecurity health to a few multiple major corporations as opposed to India, where establishments of all scales and the government have pivotal influences. Calculating the weights for sub-areas such as the resilience of key operators and cybersecurity investments will have to, therefore, differ vastly between the two nations. Therefore, it should be ensured that the weights used for aggregation are themselves standardised aggregations of various parameters pertaining to each indicator. From the information available from the framework and methodology note, it is unclear how the index handles this standardisation for a fair comparison.

Between India and the Republic of Korea, a significant amount of standardisation is required to ensure that the cybersecurity of these nations is compared fairly. The Republic of Korea has an economic environment that ties down most of its cybersecurity health to a few multiple major corporations as opposed to India, where establishments of all scales and the government have pivotal influences.

Moving towards cyber resilience

Rather than limiting the evaluation of cybersecurity to reactive means as the CSI does, it is crucial to evaluate the capability of a nation to approach threats in cyberspace preventively. What the world needs to move towards is cyber resilience, where the focus lies on ensuring that cyber threats are unlikely to appear due to proper preventive measures in place. This can be achieved by re-designing the current CSI to be divided into two approaches at the sub-index level to account for preventive and deterring factors.

The division allows for a close focus on how each nation plans and operationalises capacity-building initiatives. The current CSI places such indicators under cyber hygiene where their significance is ambiguous. Moreover, this placement would present a clearer vision of the crucial role it plays in this new conception of cyber resilience. This would also mandate segregating cybersecurity policy into two based on how ‘future-proof’ it is. The CSI framework employs a comprehensive structure of indicators to evaluate cybersecurity policy and legislation, to which this criterion would synergise to provide clarity on both the deterring and preventing aspects of cybersecurity.

Pranoy Jainendran is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV

.png)