.png)

On 20 June, the Indian External Affairs Minister, Dr S. Jaishankar visited Sri Lanka on his first official visit after his reappointment. The highlight of the visit was the commissioning of the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC), which is being built with the help of a US$6-million grant from India. With a centre in Colombo, a sub-centre in Hambantota, and multiple installations throughout the country, Sri Lanka welcomed this assistance and expressed confidence in deepening maritime security cooperation. This welcome gesture demonstrates a growing dilemma in Sri Lanka’s security calculus where it is opposing the ever-increasing power competition in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) while leveraging its geopolitical location to further its security goals and interests. It is thus important to understand how the evolving maritime geography shapes Sri Lanka’s security thinking.

Old geography, new complexities

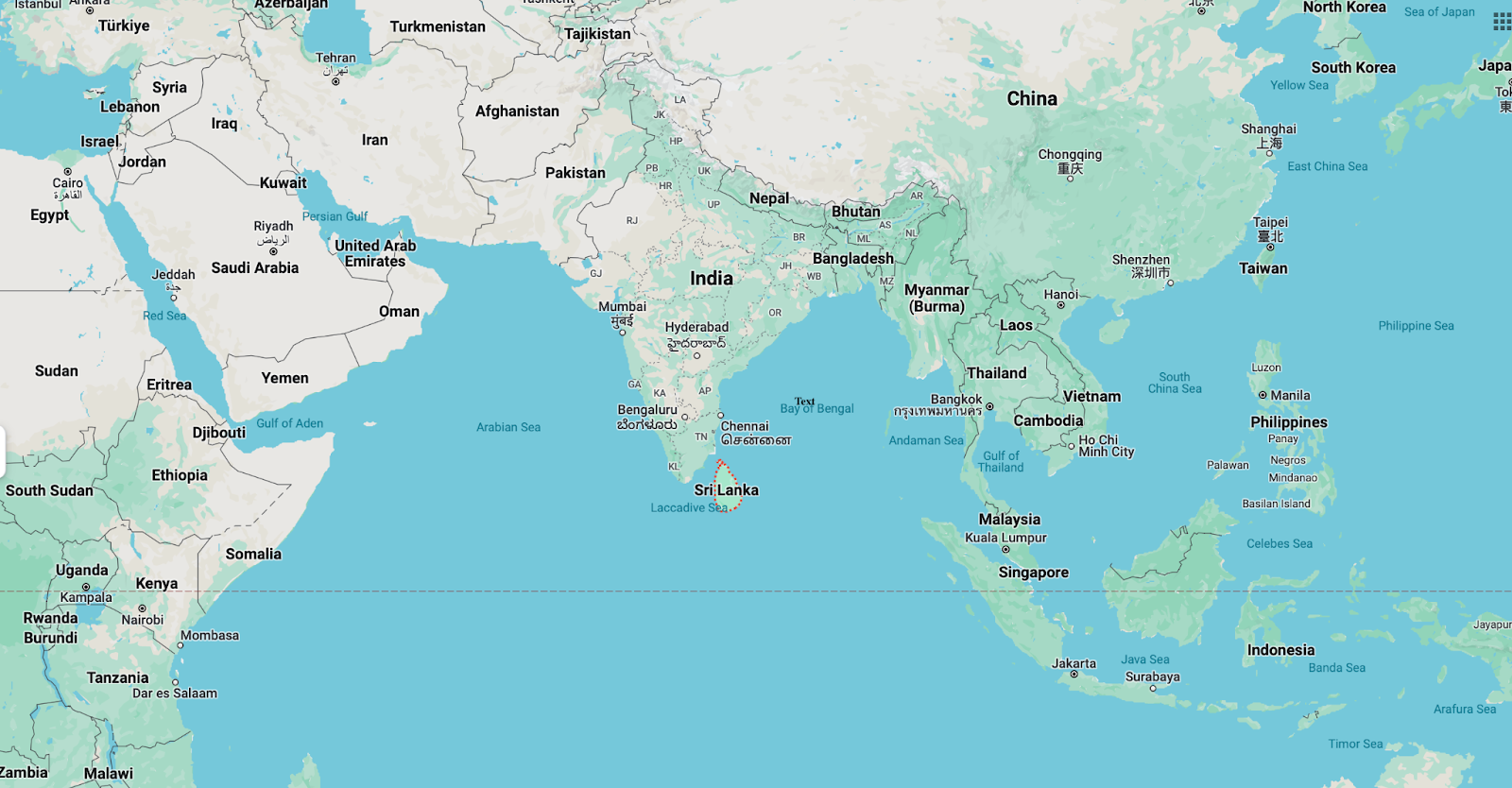

Sri Lanka, a small island nation in the IOR, has been influenced by its geography since time immemorial. Its positioning (see Map 1) between Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia not only influenced its economy and culture but also prompted extra-regional powers to play a crucial role in the country’s administration and domestic politics. From the campaigns of Cholas and Pandyas to the Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonisation, major powers have attempted to control crucial trade points and the economy. Sri Lanka’s positioning has thus shaped its politics, security calculus, and foreign policy.

Sri Lanka, a small island nation in the IOR, has been influenced by its geography since time immemorial. Its positioning between Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia not only influenced its economy and culture but also prompted extra-regional powers to play a crucial role in the country’s administration and domestic politics.

As a result, post-independent Sri Lanka has maintained a policy that avoids military alliances, refrains from conflicts in the IOR, and promotes the region as a “Zone of Peace”. This is also shaped by its non-alignment foreign policy that keeps the island nation from being drawn into power blocs, offers the flexibility to practice agency, and further its interests, and uphold its security and sovereignty.

However, as the world order shifts from the West to the East and economies like China and India continue to rise, the IOR has become a crucial point of geopolitical churning. This increasing importance has placed Sri Lanka under a significant spotlight. Located strategically between the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, countries are trying to woo the island nation to increase their presence and secure their supply chains and crucial sea lines of communications.

Map 1. Sri Lanka’s positioning

Source: Google Maps

Regional security: The makers and the shapers

China’s geopolitical aspirations and economic growth increased its presence in the IOR since the early 2000s. This coincided with Sri Lanka’s isolation during the final phase of the Eelam war and its search for new partners for post-war development. For China, Sri Lanka offered a crucial geopolitical and economic footing. It assisted the country with several mega-infrastructure and connectivity projects that were institutionalised with the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). From 2005-2019, Chinese FDI culminated to US$5 billion, and finance (loans) increased from 0.45 billion in 2006 to 12 billion in 2019. Extensive borrowing with low prospects of returns also compelled Sri Lanka to offer the strategic Hambantota port and the Colombo Port City (CPC) project on a lease to China for 99 years (see Map 2). This economic leverage has increased Chinese presence in the region and compelled subsequent governments to be sensitive to its interests and aspirations. Multiple episodes of Chinese submarines and spy ships docking in the country illustrate how Beijing weaponises its investments and debt-restructuring negotiations to militarise the IOR. Even today, Sri Lanka owes nearly US$7 billion to Beijing—the highest amongst all the bilateral creditor.

China’s geopolitical aspirations and economic growth increased its presence in the IOR since the early 2000s. This coincided with Sri Lanka’s isolation during the final phase of the Eelam war and its search for new partners for post-war development.

On the other hand, India, a traditional player in the region, has also increased its presence in Sri Lanka. The last two decades have witnessed China’s economic influence, political networks, and investments push back against India, with the Sri Lankan government seldom respecting Indian sensitivities. It was also due to the Rajapaksa brothers’ (2005–2015; 2019–2022) preference to work with China for domestic and economic reasons. However, the onset of the economic crisis in late 2021 saw India offering assistance of US$4.5 billion. It used the opportunity to increase its presence, influence, and connectivity with Sri Lanka. For instance, India will be operating the West Container Terminal of the Colombo port—adjacent to CPC, managing an airport in Hambantota, and likely running three more airports. India is also developing oil tanks in Trincomalee - another strategic city, and developing it as a regional hub. Other countries like the United States (US), Japan, France, Russia, and Australia have also increased their presence in the country to have a stake in the evolving great power politics. The US has also offered nearly US$500 million to help India develop the West Container Terminal.

Map 2. A map of Sri Lanka

Source: Google Maps

This crowding of the region is impacting Sri Lanka's security and strategic calculations, therefore, placing its non-alignment and traditional security calculus under significant stress.

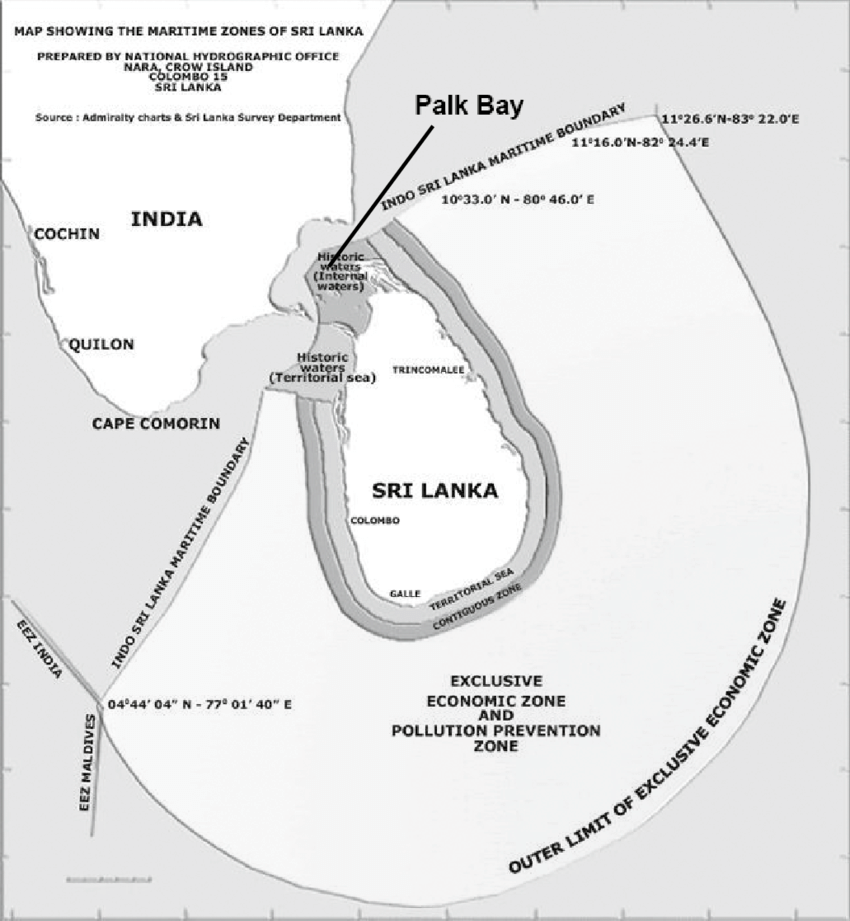

The economic crisis has further compelled Sri Lanka to recalibrate its security thinking. The onset of the crisis indicated the need for judicious use of resources and addressing non-traditional threats. Therefore, convincing the government to do more to promote growth, maintain food and energy security, secure sea lines of communications, and exclusive economic zones, and counter challenges of trafficking and illegal fishing (see Map 3). In 2023, Sri Lanka even unveiled a vision of the IOR to promote a free and open Indo-Pacific, protect undersea cables, combat illegal fishing and trafficking, address environmental issues, and offer disaster relief. This has motivated the country to play an increasing role in the IOR and deploy its patrol vessel in the Red Sea to help the US’s operation “Prosperity Guardian” to avoid trade disruption and inflatory pressures.

Map 3. Sri Lanka and EEZ

Source: ResearchGate

Strategic dilemma

To counter maritime challenges, Sri Lanka is upgrading its military capabilities. There is hope that this development would help the country secure its territories and explore its resources, without overcrowding of the IOR. At present, the Sri Lankan government is pushing for defence modernisation to make the force leaner, well-equipped, and external threats oriented. The government is keen to decrease military size from 200,783 to 1,35,000 this year and 100,000 by 2030, aiming to reduce the army and strengthen the Naval and Air forces. The Defence Review 2030 of the government also includes a strategic vision, power posturing, and outlining defence objectives and security interests. Sri Lanka has also issued a year-long ban on docking or employing foreign research vessels to avoid pressure from other countries, weaponisation of the ocean beds, and promote its own capacity to be an equal research partner.

To counter maritime challenges, Sri Lanka is upgrading its military capabilities. There is hope that this development would help the country secure its territories and explore its resources, without overcrowding of the IOR.

That said, policymakers in Colombo are using their agency to attract assistance from other major powers—further fueling the competition. For instance, on security cooperation, Sri Lanka is receiving a Dornier aircraft, a floating dock facility, an MRCC, and a small arms manufacturing unit from India. It will also join India’s Information Fusion Center. This is in addition to the latter offering of three Offshore Patrol Vessels. China, in 2019, donated a frigate to Sri Lanka and recently granted bomb disposal equipment. It has also involved Sri Lanka in its Global Security Initiative. The US has offered three coastguard cutters and military hardware. Australia, which had granted two patrol vessels in the past, continues to grant ship engines. Australia and the US are each offering a Beechcraft aircraft too, and France will be establishing a Maritime Safety and Security School at Trincomalee.

Such competition is also increasingly visible in other areas, including energy and economic security. A recovering Sri Lanka, keen on judicious use of resources and privatisation of loss-making state-owned enterprises' is now seeing countries contest for energy projects, ports, and other critical infrastructure. For instance, India and China are competing to have a stake in the telecommunications sector. In fuel retailing sector, where only Indian firms operated in the past, Sri Lanka has now invited Chinese, American, and Australian firms. China is investing over US$4.5 billion to develop an oil refinery in Hambantota while India is keen on connecting Sri Lanka with a bi-directional energy grid and oil pipeline. Thus, feeding into the competitive politics that the country desires to avoid.

Sri Lanka is a classic example of how geography determines a country’s security considerations and calculations. While Sri Lanka is pushing for domestic reforms and defence capacities to counter the emerging threats, its location prevents it from escaping the competitive power politics of the region. Furthermore, considering its traditional and new security needs, the country is also leveraging its geopolitical positioning and inviting more competition. This has introduced new dilemmas to Sri Lanka’s security calculus. How this dilemma will be dealt with will depend on how the policymakers define their priorities, and bridge the mismatch between their foreign policy, security goals, and domestic needs.

Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

.png)

PREV

PREV

.png)

.png)