Image Source: Getty

This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2025

As the world watched the Trump administration impose 10-percent additional tariffs on China’s exports to the United States (US) and threaten yet more action to contain China’s supply chain and technological rise, it is easy to forget that European Union (EU)-China relations have also gone through a sea change over the past decade. Perceptions of China in Brussels and other European capitals have changed fast following mounting concerns over China’s unfair trade practices, a more assertive Chinese foreign policy, and rising tensions between China and its neighbours. China’s “no limits” partnership with Russia, despite and amidst its war of aggression against Ukraine, have marked an inflection point in Europeans’ view of their main Asian economic partner, and pushed the relationship out of its economics-first tracks. More recently, worries over China’s overcapacities and their global trade spillovers have heightened too, and turned Europe’s long-lasting concerns over China’s distortive economic practices into a much more existential worry.[1]

While the past eight years of the US’s multi-pronged and whole-of-government actions on China have monopolised much of the headlines of global pushback against Beijing, measures taken by the EU to respond to China challenges have also seen an uptick. Brussels and key member state capitals have shed the naivety of the past, and not only buttressed their defensive toolbox but also started to use it to its full extent. The past two years have seen the European Commission launch a record number of trade defence cases against China (as many as 20 cases targeting Chinese firms and practices, out of a total 32 in 2024).[2] This included probes launched on the initiative of the Commission (“ex officio”), most prominent of which is the anti-subsidy investigation into China-made electric vehicles (EV) that resulted in tariffs last October.

In the past two years, Brussels also aimed its new defensive tools—the International Procurement Instrument and the Foreign Subsidies Regulationa—at Chinese economic practices in the wind energy, security equipment, and medical devices sectors, among other targets. Beyond Brussels, member states have tightened their inbound investment regimes to better tackle risks from (especially Chinese) acquisitions of European tech companies and critical infrastructure. Some have even started banning certain Chinese suppliers in power generation projects out of cybersecurity concerns.[3] Debates are ongoing, finally, about the EU’s economic security agenda, de-risking objectives, and need to rekindle European competitiveness.

Weighing the Impact of the EU’s Newfound Activism

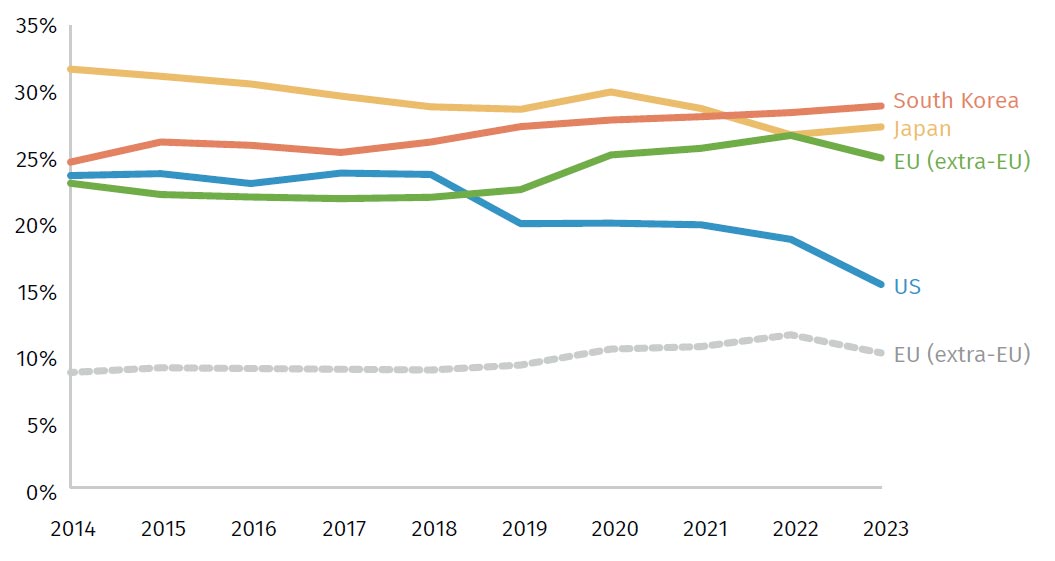

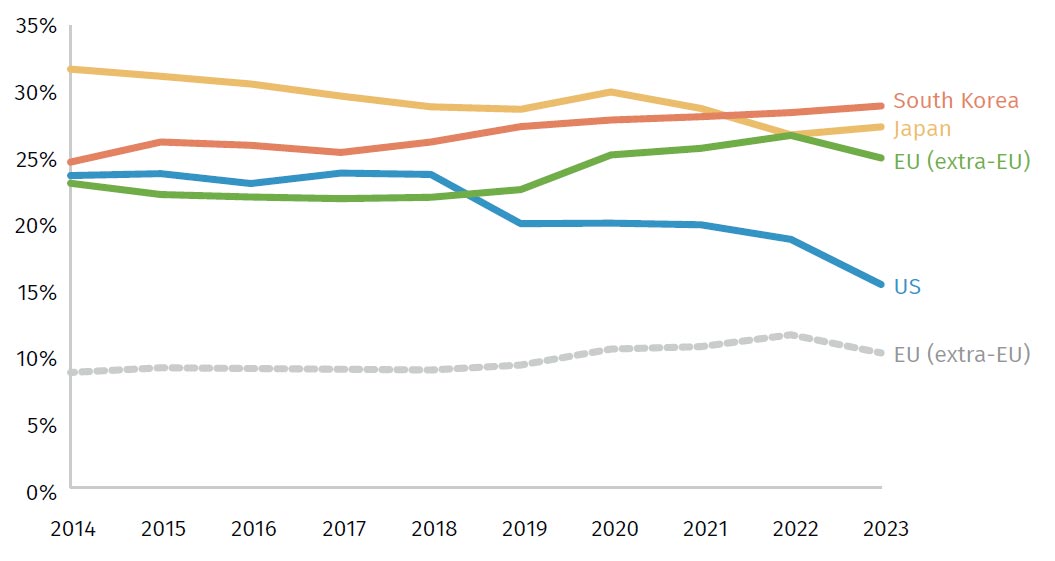

Yet, Europe’s new China activism has so far had a much more limited effect on EUChina economic ties, compared to US actions. While the US has seen a marked decline in its reliance on Chinese imports since the first trade war started in 2018, the EU has increased its dependence on Chinese goods and inputs (see Figure 1). While US foreign direct investment (FDI) in China is declining as a share of total US FDI, and Chinese FDI in the US remains at an all-time low, Chinese firms invested 48 percent more in Europe in 2024 compared to 2023, and European greenfield FDI in China is at a historical high.b Europe is much more at risk than the US from China’s economic and strategic choices, too. Its dependence on Chinese critical minerals and green-tech inputs is increasing from an already high basis, and its vulnerability to Chinese overcapacities is stark. b According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and Rhodium’s Cross-Border Monitor.

Figure 1. China’s Share of Partner Imports, Excluding Oil and Gas (2014-2023, in %)

Source: International Trade Centre[4]

The reason for this gap is a very different policy mix: Europe is much more focused on slower-to-deploy, often much narrower, and stubbornly World Trade Organization (WTO)- compliant trade and economic defensive tools. Europe’s much greater openness to Chinese green-tech imports and inputs, and far more limited financial support to major European industries, has also played a big role in the marked differences in EU and US outcomes. The lack of clear high-level EU messaging on de-risking (beyond broad and often unrealistic objectives, such as the ones set out in the Net Zero Industry Act) and of efforts to promote alternative production or sourcing bases for companies, has also played against European firms’ willingness to diversify away from China. Today, instead, the narrative has become one of “diversification fatigue” in business circles. Finally, in the European context, more defensive China policy actions have not been universally supported by EU member states. Germany’s opposition on the EV duties is one example, and Hungary’s warm welcome to Chinese FDI is another.[5] In the US, by contrast, there is a deep bipartisan consensus on China.

Which Way Forward?

Against this backdrop, what can be expected going forward? After a tense 2024, that saw tit-for-tat escalation between the EU and China on the trade and export control fronts, relations have entered a period of suspended animation as Brussels and Beijing struggle to make sense of the new Trump administration and its implications for geopolitics.

Trump-induced insecurities are pushing EU leaders to hedge their bets. Resentment of recent US trade actions (including Trump’s reimposition of steel and aluminium tariffs following a multi-year truce under Biden), and concerns of more to come, run deep. However, transatlantic irritants have become broader. US demands have moved beyond the realm of trade and defence spending to what are seen as attacks on Europe’s liberal democratic values and its efforts to curb the excesses of Big Tech. Trump has even threatened to take Greenland by force. The exclusion of Ukraine and Europe from the US’s peace talks with Russia, and US Vice President JD Vance’s meddling in European politics at the Munich Security Conference in February, have Europe worried that a new era is dawning, in which the US will be seeking to weaken and undermine it on the economic, political, and strategic fronts.

These actions put the entire bloc in a vulnerable position and explain the recent rhetorical shift on China that has been seen from European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and other senior EU officials. At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, von der Leyen suggested that while the EU’s concerns about China remain, the bloc could be open to deepening trade and investment ties going forward.[6] Von der Leyen reiterated the message at an annual meeting of EU Ambassadors in early February.[7]

So far, this soft pivot is not underpinned by substance: the Europeans have not changed their policies toward China nor unveiled new plans to engage at the highest levels with Beijing. However, if Brussels feels under attack on multiple fronts from the US, it will seek to reduce tensions with Beijing. This could lead both sides to pursue talks aimed at shelving their main trade disputes—for example through a minimum import price deal on China-made EVs, in exchange for a withdrawal of Chinese trade defence cases against brandy, dairy, and pork. This year could even see Europe and China finding a new impetus for bilateral dialogues on climate and green technologies, especially if Beijing shows willingness to ramp up investments in Europe.

Still, the barriers to a meaningful improvement in EU-China ties remain high. The EU’s concerns about China have not changed—and if anything, they are likely to grow in 2025. The EU’s industrial base and job market is likely to come under increasing strain from Chinese imports as structural imbalances persist in China’s economy, and the US locks Chinese products out of its market. China’s deepening economic relationship with Russia will remain a source of concern, even if a peace deal for Ukraine is achieved. Europe’s array of trade and level-playing-field cases against China will move ahead, with many coming to fruition in 2025. China is likely to respond with coercive action around critical minerals and other inputs, highlighting dependencies and heightening concerns.

For now, there are no signs that China is prepared to address the EU’s core concerns around overcapacities and its relationship with Russia. With the US putting in question decades of close transatlantic partnership, Beijing likely views the EU as especially vulnerable and has little incentive to make concessions. More likely than a full-blown reconciliation is a push by both sides to reduce the temperature in the relationship from a boil to a low simmer. Potential Implications for India

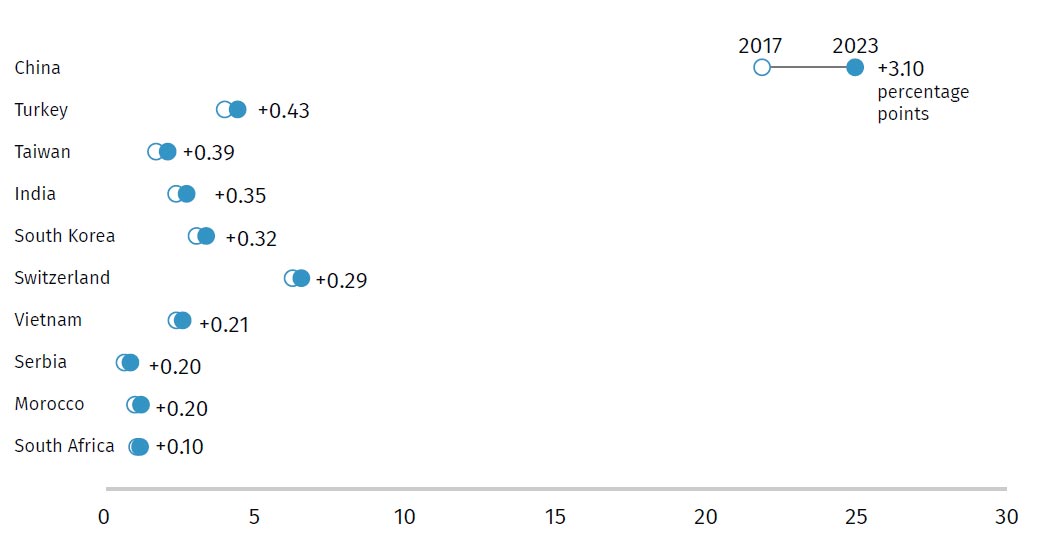

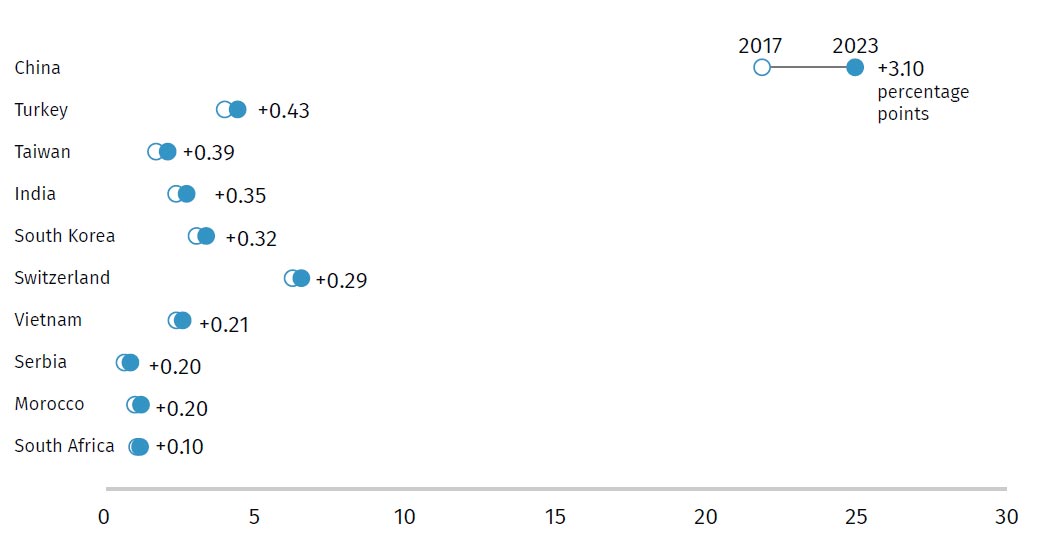

India has over the past few years emerged as an “alt-China” destination for various countries—first and foremost the US, but also Europe (see Figure 2)—particularly in sectors like mobile phones and solar PVs. To be sure, the country has not yet managed to attract interest at the levels of Mexico or Vietnam,[8] due to trade and investment barriers, and regulatory and administrative complexities. However, an overconcentration of supply chains in Vietnam and Mexico is becoming a liability, and ultimately, India is the only country with the size and scale that could replicate China’s manufacturing efficiencies.

Figure 2. Trade Partners with the Largest Positive Change in Their Share of EU Imports, Excluding Oil and Gas (2017 & 2023)

Percentage point change, extra-EU imports

Source: International Trade Centre[9]

Note: This graph includes only extra-EU trade. HS product codes 2709, 2710, and 2711 (oil and gas) excluded.

In the short term, in a context of US tariffs, it will be a tall order for Europe to diversify further. However, in increasingly geopolitical times, de-risking from China is unlikely to wane as a policy and business objective. India’s human and market strengths, as well as fast-paced growth, make it a difficult-to-ignore destination for manufacturing, sourcing, and market diversification. This will foster significant opportunities to grow two-way trade and investment ties.

India is also a prime option for “diplomatic diversification”, as demonstrated by the fact that India will be the destination for the first foreign trip of the new Commission. Opportunities for closer EU-India cooperation abound—these could include partnerships on connectivity (including via the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor) and industrial and technological cooperation on green technologies such as hydrogen, climate finance cooperation, enhancement of people-to-people flows and research and innovation ties, and critical supply chain de-risking initiatives.

Trump’s decisions will matter here too. India’s ability to ride the current diversification wave hinges on continued domestic reforms, but also on US tariff and tech policies that will affect the restructuring of global supply chains. It will also depend on Washington’s willingness to present India as a secure and stable long-term strategic and economic partner. The recent US-India summit provided a strong signal to that effect. And in the current context of heightened trade tensions between EU and its main trade partners, Brussels will be looking for alternatives—much to India’s benefit.

Endnotes

[a] The International Procurement Instrument (IPI) regulation aims to promote reciprocity in access to international public procurement markets, while the Foreign Subsidies Regulation grants the European Commission the power to investigate financial contributions granted by non-EU governments to companies active in the EU.

[lb] According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and Rhodium’s Cross-Border Monitor.

[l] Camille Boullenois, Agatha Kratz, and Daniel H. Rosen, “Overcapacity at the Gate,” Rhodium Group, March 26, 2025, https://rhg.com/research/overcapacity-at-the-gate/; Camille Boullenois and Charles Austin Jordan, “How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies,” Rhodium Group, June 18, 2024, https://rhg.com/research/how-chinas-overcapacity-holds-back-emerging-economies/ Júlia Palik, Siri Aas Rustad, and Fredrik Methi, “Conflict Trends in Africa, 1989–2019,” PRIO Paper (2020).

[2] “Trade Defence Investigations,” European Commission, https://tron.trade.ec.europa.eu/investigations/ ongoing

[3] https://www.pv-tech.org/lithuania-to-block-chinese-inverters-with-cybersecurity-legislation

[4] “Trade Map,” https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx

[5] Jens Kastner, “German Vote Against EV Tariffs Undercuts EU’s Tougher China Stance,” Nikkei Asia, October 4, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade-war/German-vote-against-EV-tariffs-undercuts-EU-stougher- China-stance; Agatha Kratz et al., “Dwindling Investments Become More Concentrated - Chinese FDI in Europe: 2023 Update,” Rhodium Group and MERICS, June 6, 2024, https://merics.org/en/report/ dwindling-investments-become-more-concentrated-chinese-fdi-europe-2023-update

[6] World Economic Forum, “Davos 2025: Special Address by Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission,” January 21, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/davos-2025- special-address-by-ursela-von-der-leyen-president-of-the-european-commission/

[7] European Commission, “Speech by President von der Leyen at the EU Ambassadors Conference 2025,” February 4, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_404

[8] Agatha Kratz et al., China Diversification Framework Report, Rhodium Group, 2024, https://rhg. com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Rhodium-China-Diversification-Framework-Report-BRT-Final- Draft_21Jun2024.pdf

[9] “Trade Map”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV