The expression ‘economic reforms’ is back in the governance lexicon of India. With the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) bringing nations to a physical slowdown if not a complete standstill, and jobs and GDP growth becoming collateral damage, the mere announcement and phraseology of reforms seems to have become a solution. Unfortunately, and perhaps its early days, communication rather than action, words rather than deeds, and tactics rather than strategy seems to be dominating the discourse.

And yet, within the constraints set by the pandemic and fire-fighting the virus being the primary action agenda, there are several green shoots of real reforms happening under the word, within the past one month. These are in three key governance areas – the Union government, the state governments, and surprisingly, the judiciary. The only missing link for now is the legislature, in Parliament as well as in Legislative Assemblies, which are shut for now under the lockdown.

Unfortunately, and perhaps its early days, communication rather than action, words rather than deeds, and tactics rather than strategy seems to be dominating the discourse.

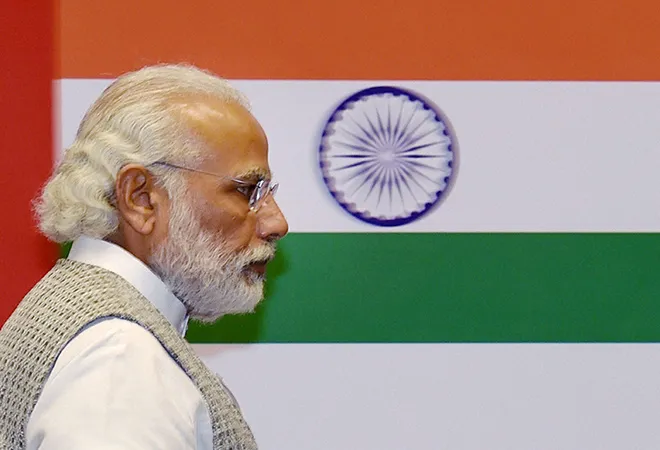

Big economic reforms were last seen in 1991 when the economy opened up by reducing licences and permits. Since then, there have been a series of reforms, none of which have matched the concert of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao and then Finance Minister (and later Prime Minister) Manmohan Singh. Under incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has seen a handful of reforms such as the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax, the Indian Bankruptcy Code or the JAM trinity that gave bank accounts to the unbanked (Jan Dhan), identity (through Aadhaar) and tied together by a mobile phone. But 1991 remains the pinnacle of big think around integral economic reforms, the fruits of which have been digested.

As a young nation now seeks bolder, stronger, more effective change, COVID-19 has put India in the middle of the perfect storm for deep reform. Painful as the health and economic impact may be, the pandemic has provided the right conditions to usher in this change. Cries for mega reforms have been coming for years now. But despite the majority in Parliament, Modi has been a reluctant reformer, banking on incrementalism rather than big bang changes. That said, Modi’s 12 May 2020 Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) speech raised expectations of mega reforms, it gave a signal that the Indian government machinery is finally on the move. So far, the results have been lagging the expectations in scale, even if they are progressing forward in short steps.

Cries for mega reforms have been coming for years now.

Reforms initiated by the Union government

On 3 June 2020, the Union Cabinet approved three big legislative changes, which Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced two weeks earlier in the first of her five-tranche economic stimulus package. Together, this troika has embraced agriculture reforms squarely.

First, it approved an amendment to the Essential Commodities Act, 1955, under which some food items such as cereals, edible oils, oilseeds, pulses, onions and potatoes will be deregulated, unless under “very exceptional circumstances like national calamities or famines.” With this end fears of private investors of excessive regulatory interference in business operations. Enacted 65 years ago, the law enabled the government to regulate the production, supply and distribution of ‘essential’ commodities such as drugs, oils, iron, steel and pulses to ensure their availability to the people at fair prices. But like every policy that attempts to control one part of a market, this law ignored nature — it prevented building up inventory during harvest season and drawing down from it in the lean season. Further, the law distorted incentives for and prevented the creation of storage infrastructure by the private sector. This, in turn, prevented the upgradation of the agricultural value chain and development of national market for agricultural commodities. With these hurdles out of the way, investments into agriculture should start.

Second, the Cabinet approved ‘The Farming Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020’, which frees the farmers to sell their produce to economic agents other than the powerful Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC), bodies licenced by state governments. The law will put an end to state-level institutional monopsonies through collective cartelisation of licence-wielding agents in the food market and promote barrier-free inter-state and intra-state trade and commerce outside the physical premises of markets notified by state laws. Agriculture being a state subject under the Constitution, this is really a consolidation of work in progress. States governed by the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) have already made changes to their laws. Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh, for instance, have put in place Ordinances to dismantle their respective APMC laws, while Gujarat has allowed private entities to set up their own market committees. These policy actions will open more choices for the farmer, reduce their marketing costs and help them get better prices. And through it, attempt a huge change in agriculture through a “one India, one agriculture market” mantra. How this plays out, particularly in non-BJP governed states will be interesting exercise in Union-State relations.

And third, the Cabinet approval to ‘The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020’. While the details about this law are not clear, the government claims that it will enable farmers to engage with processors, wholesalers, aggregators, retailers and exports on a “level playing field”. Further, it will “transfer the risk of market unpredictability from the farmer to the sponsor and improve income of farmers”. Finally, while the sale, lease or mortgage of farmers’ land is prohibited, an effective dispute resolution would be provided in the law.

Together, this troika has embraced agriculture reforms squarely.

The other big reform Sitharaman initiated was in opening up the space and atomic energy sectors. The former allows private firms to launch satellites and space-based services. One of the few government run organisations that stands at the cutting edge of technology, the research facilities of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) would now be accessible to private entrepreneurs, who would be able to leverage them commercially, opening the door for an Indian Elon Musk. Likewise, the government has allowed private sector to establish research reactors in atomic energy to produce medical isotopes and use irradiation technology for food preservation, under the public-private partnership (PPP) mode.

Reforms initiated by state governments

Although Modi’s speech laid the path of land and labour reforms, the former is a state subject and the latter on the concurrent list. Being a political hot potato, while no government will touch land, on the issue of labour reforms two BJP-governed states — Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh — led the initiative, both in different ways. Over two consecutive days, while the former will make the landlocked state a better place to do business, the latter overshot its brief and has had to withdraw the badly-thought reform.

In a 7 May 2020 statement, the four-term Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan showed the maturity of experience and clarity of thought in bringing about four sets of reforms in labour laws of Madhya Pradesh, all around processes. First, registration reform: Chouhan has made officers accountable to ensure registration will be done in one day. Second, licences reform: all licences to set up a factory have been extended for 10 years from one. Third, returns reforms: the number of registers a business is expected to fill has been reduced to one from 61, the number of returns has been cut to one from 13. Further, self-certification would be adequate: this has reduced the number of inspections. And fourth, labour reforms: factories employing less than 50 employees will not be inspected, while thresholds on number of workers has been raised. Chouhan also spoke about a dispute resolution mechanism without the courts but that still needs to play out.

Being a political hot potato, while no government will touch land, on the issue of labour reforms two BJP-governed states — Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh — led the initiative, both in different ways.

On the other side, in his 8 May 2020 notification, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath showed a tearing hurry that has smothered his aspiration for creating a more industry-friendly state. Through the Uttar Pradesh (Temporary Exemptions from Certain Labour Laws) Ordinance 2020, he suspended minimum wages and safety laws pertaining to businesses in the state. These moves would not pass either the Union government’s executive signature (needed because labour is a subject on the concurrent list), or judicial scrutiny. Even before the Ordinance moved forward, a public interest litigation dragged it to the Allahabad High Court, following which Adityanath withdrew the Ordinance. Details of the Ordinance and nobility of aspirations aside, to plan these changes just for three years shows that the Uttar Pradesh government is completely out of synch with business realities — it takes anything between 24 and 30 months for a factory to come up. Where, then, is the space for relaxations?

Reforms initiated by the judiciary

The final piece of reform has come from an unexpected quarter — the judiciary. Best known for standing against any change, this time the Supreme Court has initiated process reforms in the way the higher judiciary initially and lower courts subsequently functions. By embracing artificial intelligence and other technologies, India’s highest court has pushed for efficiency-inducing change in court processes — filings, submitting extra material, payments of fees, verification practices or submissions. This can end the pain points of court processes for those seeking justice. Beginning 15 May 2020, these processes have been initiated, virtual hearings have started and e-filings have become the route to justice. This is a never-seen-before disruption in the way the higher judiciary of India functions and is in tune with a 21st century India. In the short term, and amid the fewer number of cases being taken up due to COVID-19, initial reports have been positive. The test will happen once India gets out of the lockdown. If pendency of cases gets reduced, we would know the new system works.

By embracing artificial intelligence and other technologies, India’s highest court has pushed for efficiency-inducing change in court processes — filings, submitting extra material, payments of fees, verification practices or submissions.

If a crisis was needed to reform a nation, perhaps COVID-19 it is. Recall the 1991 reforms, when India was facing a balance of payments crisis. The crisis pushed the Indian state into action and economic reforms were quickly ushered in. This time, the health emergency may last longer, the time to deliver economic reforms shorter. Within these constraints, the Indian state seems to have come together. How this plays out going forward remains to be seen. While the green shoots of reforms are visible, an entire forest remains to be seeded. One thing is certain: if governments (Union and states) do not deliver reforms now, they will go down in history as having lost the greatest opportunity for change in a country as difficult to govern as India.

This commentary originally appeared on ISPI.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV