This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2021.

Supply chains for critical and emerging technologies face mounting scrutiny in the wake of two related disruptions — one precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the other by tensions between the world’s two largest economies, China and the US. Decades of efficiency-driven shifts that gave rise to the global supply chain have also made them fragile and riddled with bottlenecks. At the same time, the need to verify the “trustworthiness” of suppliers has created an added layer of scrutiny.

Decades of efficiency-driven shifts that gave rise to the global supply chain have also made them fragile and riddled with bottlenecks.

However, what does the concept of “trusted supply chains” mean in this evolving context? Depending on the “who” and “where” attached to this question, “trusted” can variously mean secure, transparent, adaptive, ethical or stable.

This brief will identify characteristics of global supply chains for critical technologies, highlight the various ways different actors define “trusted supply chains” and then present some core characteristics of this emerging narrative.

The meteoric rise of global supply chains

The evolution of global supply chains is linked to what economist Richard Baldwin characterised as globalisation’s “unbundlings” — the unbundling of production and consumption triggered by the industrial revolution (1820s-1990); and the unbundling of stages of production, or offshoring triggered by the information and communications technology revolution (1990s-present). Baldwin also proposed a “third unbundling”, the unbundling of physical labour from the individual due to developments in the internet of things (IoT), robotics and other emerging technologies that will enable workers in one location to perform physical tasks in another. These unbundlings were driven by profitability — production and other tasks are offshored to countries with lower factor costs, including wages. Offshoring is also driven by a country’s specialisation in certain activities, and a conducive regulatory and institutional environment. Specialisation involves heavy costs at the outset but results in a comparative advantage and helps a country to entrench itself within the global supply chain.

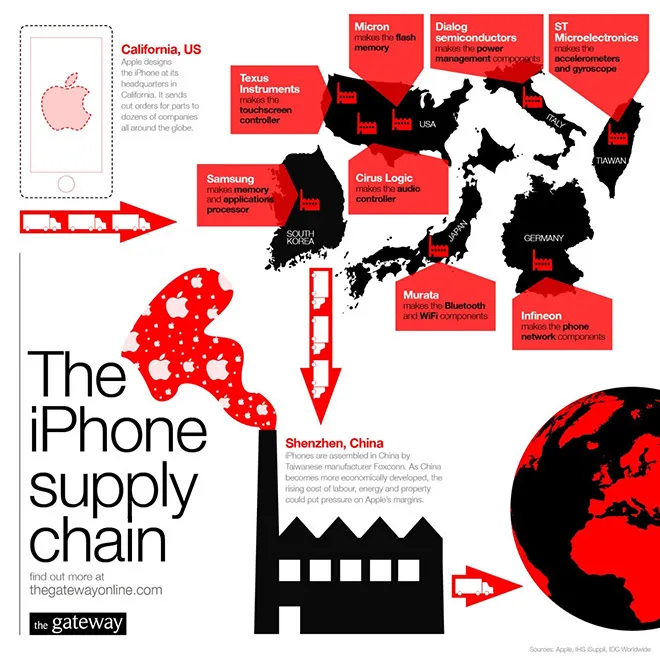

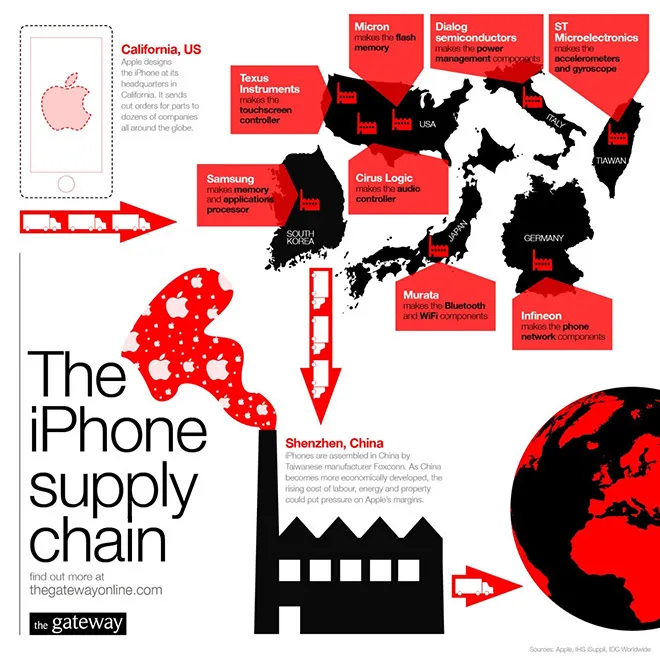

Modern supply chains for many technologies are, therefore, multi-layered and vast, ning several countries, with each specialising in specific components and services.

One need only look at the humble iPhone to get a sense of the scale and complexity of these supply chains.

“Increasingly, firms across advanced and developing countries add value along these global supply chains by completing a specific task associated with the production of a finished product and then exporting it. This may be an important part or component required in the production of a good. It may even be a service that is a vital intermediate input in further production.”

One need only look at the humble iPhone to get a sense of the scale and complexity of these supply chains. As a starting point, look to Apple’s Supplier List, which includes 200 suppliers in 25 countries. However, accounting for overseas subsidiaries of the same supplier, China comprises the lion’s share of Apple’s supply chain, with the US, Japan and Taiwan wrapping up the top four.

Figure 1: The iPhone Supply Chain

Source: The GatewayThe logic board of the iPhone 12 alone contains components from nine different supplying companies, which outsource manufacture and assembly to hubs in Southeast Asia, China, and India. These components can be further broken down into the raw materials that go into these chips, including semiconductor materials and rare earths, which in turn can come from China, Australia, Democratic Republic of Congo or any one of the world’s major producers and processors of these materials.

Source: The GatewayThe logic board of the iPhone 12 alone contains components from nine different supplying companies, which outsource manufacture and assembly to hubs in Southeast Asia, China, and India. These components can be further broken down into the raw materials that go into these chips, including semiconductor materials and rare earths, which in turn can come from China, Australia, Democratic Republic of Congo or any one of the world’s major producers and processors of these materials.

The mind-boggling complexity of a single smartphone is a microcosm for how global technology supply chains function; the disruption in supply of a single component can disrupt the entire chain. Semiconductor supply chains, for instance, are notoriously brittle, and the world is currently seeing a global chip shortage due to the combined impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration’s blacklisting of Chinese semiconductor firms (many of whom supply US tech giants, like Apple), and a shortage of shipping vessels and airfreight. Additionally, as we head into the “third unbundling”, information infrastructure is an increasingly relevant component of supply chains. The digitisation of supply chains must therefore strike a balance between transparency and security.

While disenchantment with globalisation is by no means a new phenomenon, the urgency around so-called “trusted supply chains” has intensified over the past two years.

The combined storms of trade wars and pandemics have led to a paradigm shift in the narratives around the global supply chain. While disenchantment with globalisation is by no means a new phenomenon, the urgency around so-called “trusted supply chains” has intensified over the past two years.

Trusted tech

A relatively new entrant in the global geopolitical lexicon, the concept of trust in supply chains has a history in defence and industrial management. In the national security context, trust has typically been defined in very narrow terms. The US National Defense Authorisation Act of 2013, for instance, implicitly defines “trustworthy suppliers” as those that are US-based and, by extension, easier to audit and control. The literature on technology partnerships has defined trust along two parameters — capability and commitment (or intent). Trust in supply chains in this literature is built through consistent ability to deliver upon obligations (transactional trust), complementary strengths (relational trust), and strategic alignment, whereby partners view others’ capacity and capabilities as an extension of their own (collaborative trust).

A relatively new entrant in the global geopolitical lexicon, the concept of trust in supply chains has a history in defence and industrial management.

The use of the term “trusted supply chains” (and its permutations) within its current contours has truly taken off in the past two years. Amongst technology multinationals, the term is used to reassure customers and clients, and signal reliability to regulators. Lenovo’s ‘Trusted Supplier Programme,’ for instance, emphasises its Kafkaesque audit system, including a 200-point questionnaire. Intel’s “transparent supply chain” keeps traceability at the forefront. A Google Cloud blog post on their supply chain, with direct reference to the SolarWinds, hits all the notes on a robust security architecture, transparency and collaboration. In most of these examples, there is a competitive element as well — rankings and the “world’s best” tag all underpin industry narratives.

This competitive aspect is present in political narratives as well. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, for instance, pitched India as a favoured destination for post-pandemic reshoring of supply chains: " shown the world that the decision on developing global supply chains should be based not only on costs. They should also be based on trust. Apart from geographical merits, "companies are now also looking for reliability and policy stability…India is the location which has all of these qualities."

The October 2020 White Paper by the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission (CSC) takes a similar stance, promoting globally “American and partner companies in the face of Chinese anti-competitive behaviour in global markets”. Intriguingly, the paper views efforts to build trusted supply chains as complementary but independent of efforts to secure said chains.

The EU’s efforts to build trusted supply chains hinges on strong and competitive European alternatives to critical and emerging technologies like microprocessors, quantum communications infrastructure, 5G and IoT, as well as the identification and management of “untrusted” third party vendors.

The Australian parliament’s report on the impact of the pandemic on trade makes seven mentions of “trusted supply chains,” and one of its recommendations proposes that the country be a “trusted and transparent partner of choice for like-minded nations.” The document also highlights risks to continuity of supply as an element of trust: “The key concept <…> is that of trusted supply chains and trusted sources. It may be safe to have a critical element of a market supplied by a non-sovereign source, but only if the source can be trusted to maintain supply” (emphasis added).

Security and self-reliance march in tandem with narratives on trusted supply chains. The European Union (EU) vision for a “Digital Europe” aims for “robust European industrial and technology coverage of key parts of the digital supply chain.” The EU’s efforts to build trusted supply chains hinges on strong and competitive European alternatives to critical and emerging technologies like microprocessors, quantum communications infrastructure, 5G and IoT, as well as the identification and management of “untrusted” third party vendors. In March 2021, India’s Department of Telecommunications mandated that telecommunication providers in the country use only “trusted products” in their 4G and 5G networks, with the IT minister stating simply that “the core of the network should be Indian.”

Resilience in terms of strength and reliability of institutions and policies is a component of trusted supply chains in other state narratives as well.

The Australian parliament’s report and CSC White Paper at various instances contain overlaps between ideas of trust and those of resilience. “The supplier should not be subject to major commercial or financial risk or the risk of supply interruptions due to factors such as political insecurity, armed conflict, corruption, administrative malpractice, government intervention, arbitrary policy or regulatory enforcement or vulnerability to natural and environmental disasters,” the Australian report says.

The Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s White Paper on International Economy and Trade 2020 also prioritises “resilient supply chains” that are flexible in the face of future shocks. Diversification is the key strategy proposed by the paper, including support to alternate sources of bottlenecked critical goods and services.

Resilience in terms of strength and reliability of institutions and policies is a component of trusted supply chains in other state narratives as well. Case in point is the following statement by Malaysia’s former Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng, “Our institutional reforms have also made our institutions more trustworthy and transparent.”

Defined in these various ways, what do “trusted supply chains” mean? Four threads emerge.

Security: The ability to predict, monitor and respond to threats that may affect the continuity of supply chains. Security is sometimes conflated with trust, but at other times (as in several of the documents cited in this brief) it is but one element of a trusted supply chain. This lack of clarity plagues the tech industry as well. As a post on IBM’s blog notes, “There is no single, functional definition of supply chain security. It’s a massively broad area that includes everything from physical threats to cyber threats, from protecting transactions to protecting systems, and from mitigating risk with parties in the immediate business network to mitigating risk derived from third, fourth and “n” party relationships.”

Transparency: Transparent decision processes, regular audits and responsiveness to requests for information are a staple of the “trusted supply chain” concept. This extends to the governments of the countries that suppliers are based in. Clear laws governing flows of goods and services, and transparency in governance practices and in the arbitration of legal disputes all fall under the aegis of this thread.

Resilience: Namely the ability of supply chains to recover from shocks, whether they be from natural disasters, changes in the security and economic policies of supplier nations, et al. Where security and transparency may place specific obligations on suppliers, resilience is a quality of the network in its entirety.

Likemindedness: Perhaps the least-clearly defined of the four, likemindedness appears to capture two broad ideas. The first is similarity in ideologies and, by extension, legal and political systems. Australia and the US, for instance, both emphasise democracy and open societies as a requirement to build trusted supply chains. The second is common goals, which bypasses the delicate issue of the nature of a regime and resultant disagreements partner countries may have, and instead emphasises common ends. The ambiguity of “likemindedness”, particularly in the latter instance, has brought together unlikely partners. Notable among these is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or Quad) consisting of Australia, India, Japan and the US, which began as a coalition tailored to defend freedom of navigation in the (now) Indo-Pacific, and has since expanded its ambit to connectivity, critical and emerging technologies, and supply chains.

Conclusion

The result of the increasing, politically charged scrutiny of global technology supply chains may well transform trust into one of the most valued currencies in international relations. In this vein, this brief noted the competitive aspect of the “trusted supply chain” narrative, where governments and tech giants alike have emphasised their trustworthiness as a core competency that distinguishes them in the global market.

The use of the term “trust” in this context can serve as a shorthand for reliability, resilience or continuity, call for the strengthening of the security of supply chains, or target adversaries.

Trusted supply chains will likewise become a mainstay in the formation of new coalitions centred on critical and emerging technologies. However, observers should not assume that this term captures the same ideas amongst the myriad of actors that have begun to use it. The use of the term “trust” in this context can serve as a shorthand for reliability, resilience or continuity, call for the strengthening of the security of supply chains, or target adversaries.

While the drive for efficiency and lower factor costs prompted the globalisation of supply chains in the past three decades, the contours of global supply chains in the 2020s and beyond will be shaped by the evolving understandings of “trust.”

Richard Baldwin, “Globalisation: The Great Unbundling(s),” Economic Council of Finland, 20 September 2006; Richard Baldwin, The Great Convergence: Information technology and the New Globalisation (Harvard University Press: November 2016).

Richard Baldwin, The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work (Oxford University Press: 2019).

Albert Park, Gaurav Nayyar and Patrick Low, “Supply Chain Perspectives and Issues: A Literature Review,” World Trade Organisation, 2013.

Park, Nayyar and Low, “Supply Chain Perspectives and Issues”

Apple, “Supplier List,” Apple, 2019.

Apple, “Supplier List”

The Gateway Online, “The iPhone supply chain,” Visual.ly.

iFixit, “iPhone 12 and 12 Pro Teardown,” iFixit, 20 October 2020: These companies are Kioxia, Qualcomm, Broadcomm, NXP Semiconductors, STMicroelectronics, Texas Instruments, Cirrus Logic, Bosch, Skyworks.

Martin Smodi et al., “The Content of Rare-Earth Elements in Mobile Phone Components,” Materials and Technology 52 (3) (2018), pp. 259–268.

“Rare Earths Data Sheet - Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020,” US Geological Survey.

Bindiya Vakil and Tom Linton, “Why We’re in the Midst of a Global Semiconductor Shortage,” Harvard Business Review, 26 February 2021.

B.S. Sahay, “Understanding trust in supply chain relationships,” Industrial Management & Data Systems, 2003.

Senate Armed Services Committee, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013, Congress.

Stanley E. Fawcett, Stephen L. Jones and Amydee M. Fawcett, “Supply chain trust: The catalyst for collaborative innovation,” Business Horizons, vol. 55, issue 2 (2012), pp. 163-178.

Fawcett, Jones and Fawcett, “Supply chain trust”

Andrew Barron, “Putting Trust in the Supply Chain,” Lenovo StoryHub, 3 November 2019.

Intel, “Transparent Supply Chain,” Intel.

Phil Venables and Heather Adkins, “How we’re helping to reshape the software supply chain ecosystem securely,” Google Cloud, 15 January 2021.

Kiran Sharma and Takako Gakuto, “Modi calls for 'trustworthy' supply chains, in alternative to China,” Nikkei Asia, 4 September 2020.

“Building a Trusted ICT Supply Chain,” CSC White Paper #4, Cyberspace Solarium Commission, October 2020.

“Inquiry into the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Australia’s foreign affairs, defence and trade,” Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, December 2020.

“Digital Europe for a more competitive, autonomous and sustainable Europe – Brochure,” European Commission, 20 January 2021.

“Guidelines for Securing the Internet of Things,” The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), 9 November 2020.

Harry Baldock, “India cracks down on ‘untrusted’ infrastructure vendors,” Total Telecom, 11 March 2021.

“Inquiry into the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Australia’s foreign affairs, defence and trade”

“White Paper on International Economy and Trade 2020 ,” Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, July 2020.

“Malaysia upbeat on enhancing its global supply chain,” New Straits Times, 17 September 2019.

Magda Ramos, “What is supply chain security,” IBM, 22 October 2020.

“Building a Trusted ICT Supply Chain”; “Inquiry into the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Australia’s foreign affairs, defence and trade,” Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, December 2020.

“Quad Leaders’ Joint Statement: “The Spirit of the Quad”,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 12 March 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: The Gateway

Source: The Gateway PREV

PREV