It is amusing to note that in spite of having access to death registration data from Mumbai, Delhi and Chennai, the authors of a recent article in The Washington Post have made a fallacious case that Indian cities are systematically under-reporting COVID-19 deaths. They did so by choosing to use only data from Mumbai for May 2020. Why did the authors of The Washington Post article zoom in on Mumbai’s May 2020 data? Perhaps, it could be because that is the only month in which the number of deaths was considerably higher than in the same month in 2019. With the newly published Delhi data for the quarter of April to June 2020 showing a decline in the number of deaths, as compared to the same time period in 2019, it would seem that the authors chose not to use either Chennai or Delhi data since the numbers from these cities did not fit their narrative. A close scrutiny of available information would suggest that their narrative is devoid of facts.

For instance, let’s look at Delhi. All major public, charitable and private sector hospitals in Delhi – there are 900 of them – are reporting deaths online to local authorities. The remaining smaller hospitals report the details to officials regularly. All ‘institutional deaths’ in Delhi are mandatorily medically certified and registered. Some COVID-19 patients who may have died at home for a range of reasons may be missing from the list of pandemic victims. The non-recording of these relatively small number of deaths could have been due to systemic inefficiencies and, possibly, staff shortage during the pandemic.

But are these numbers big enough to change Delhi’s very low death rate and push it towards the global average? The answer is, ‘No’. The reconciliation of death data on 16 June, which added more than 400 COVID-19 deaths from the previous months, points towards a system that works, even if slowly. Similar reconciliation of data on COVID-19 fatalities has also happened in Mumbai and Chennai – the two other cities with the highest number of deaths.

In the following enquiry, we will see how temporal analysis of death registration data to derive quick conclusions can be misleading. The fact that Indian cities cater to patients from not just neighbouring districts but neighbouring States as well, may be biasing the numbers tremendously, based on local realities. As discussed elsewhere, since the last rites of bodies of COVID-19 victims and even suspected victims are to be taken care of following a set protocol by health authorities rather than families, the cremations and burials happen within the city itself.

Has Delhi Passed its Peak?

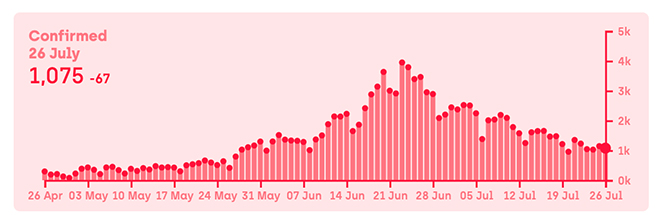

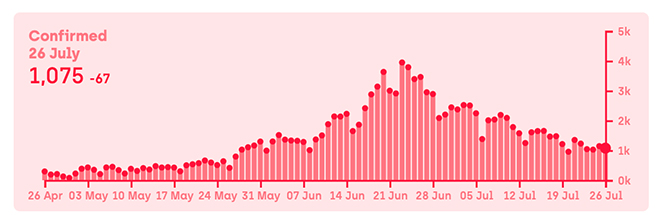

In terms of new daily recorded COVID-19 cases, Delhi is now ranked 16th among Indian States and Union Territories. In terms of daily recorded deaths, it is ranked seventh. However, when it comes to the total recorded cases and deaths, Delhi is still ranked third and second respectively. Delhi’s test positivity rate has come down to 6% from about five times that figure only a few weeks back. It certainly looks like Delhi has passed its peak since the initial wave of the pandemic. Most of the recorded cases and deaths in Delhi seem to be from the months of June and July (Graph 1), according to official numbers.

Graph 1: Daily Recorded Cases and Deaths in Delhi

Source: https://www.covid19india.org/state/DL

Source: https://www.covid19india.org/state/DL

A prominent private company, which performed 80,000 antibody tests in cities across India over the last few weeks, found that 15-16% of the population in Delhi had COVID-19 antibodies. According to this company offering antibody tests, particularly to office employees, those cities that have reported a high number of deaths are also showing a high level of sero-positivity. Some specific areas in Delhi, identifiable by their pin codes, along with those in Mumbai and Chennai, have shown sero-positivity of more than 50%, according to company officials. This pushes down the death rate further, as well as the pace of the spread.

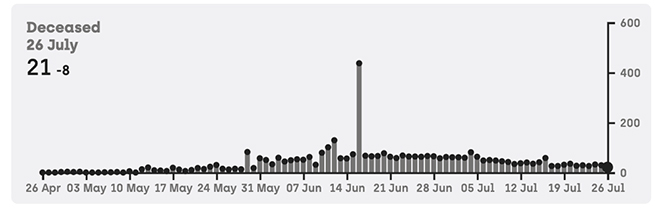

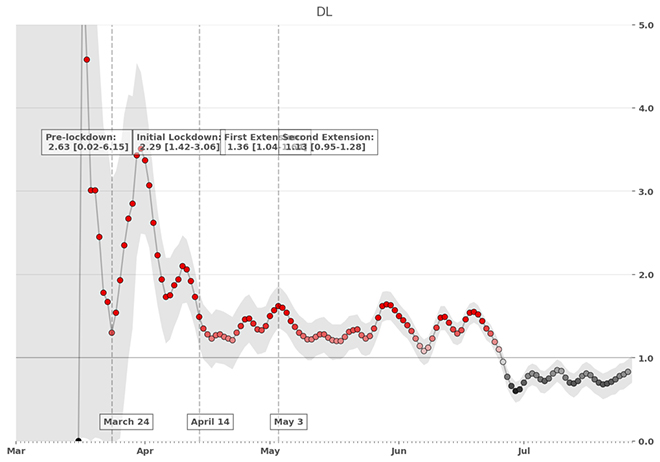

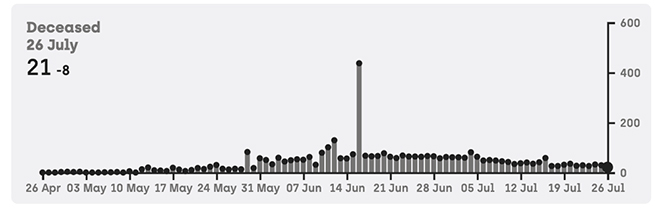

A seroprevalence survey conducted jointly by the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC) and the Delhi Government showed that by mid-June, 22.9% of Delhi’s population had had the COVID-19 infection; this is after adjusting for the accuracy of the testing kit. There is considerable variance (Graph 2) across Delhi’s districts, but it is impossible as of now to compare district-level prevalence with actual reported cases and registered deaths, as district level numbers are not published by the Delhi authorities. However, given that the number of reported deaths in Delhi, as of 27 July, is 3853, the levels of seroprevalence mentioned above make it very clear that the actual death rate in Delhi is much lower than what is generally perceived.

Graph 2: Prevalence of COVID-19 Antibody Among Delhi’s Population

Source: https://twitter.com/COVIDNewsByMIB/status/1285534811164037120/

Source: https://twitter.com/COVIDNewsByMIB/status/1285534811164037120/

The Case Fatality Rate (CFR) for Delhi, based on current official data, stands at 2.9% against the national average of 2.3%. Both these rates are much higher than the actual death rates as a vast majority of infections are missed by the health system, given our relatively low testing rates. A city of 20 million people, Delhi has yet to conduct one million tests. India, a nation of 1380 million people, has yet to conduct 17 million tests. The first national seroprevalence survey conducted by ICMR had shown that the death rate in India was possibly hugely exaggerated. In May, the difference between Case Fatality Rate (CFR) and Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) was much higher than previously thought, as actual infection numbers in May itself was estimated to be ten million, during which time official case numbers were just under a hundred thousand.

Delhi’s Real Death Rates

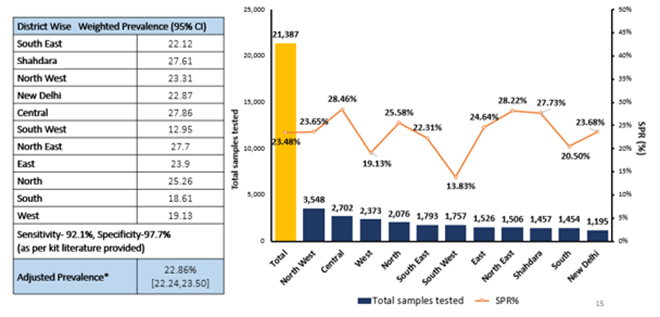

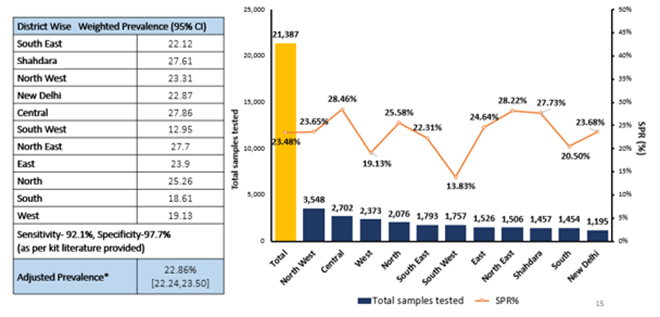

The pace of the spread of the novel coronavirus in Delhi (‘doubling rate’) may have come down since the new survey was conducted, with many pockets reaching the “herd immunity threshold” of close to 40%, given that the Effective Reproduction Number (R0) in Delhi has been closer to 1 than 2 for most parts (Graph 3) after mid-June. Still, a very conservative estimate will be that about 40% of Delhi’s population is currently infected or was infected in the past by COVID-19. The new serosurvey results prove that while recorded cases show that only 0.65% of the population of Delhi was ever infected, the truly infected are about 40% of the population. Assuming the reported number of deaths to be a closer reflection of reality, this means that the IFR is much lower than what was thought earlier.

Graph 3: Tracking Effective Reproduction Number (R0) in Delhi

Source: https://sanzgiri.github.io/covid-19-dashboards/2020/07/26/Realtime_R0_India_By_State_Upd.html

Source: https://sanzgiri.github.io/covid-19-dashboards/2020/07/26/Realtime_R0_India_By_State_Upd.html

We do have some estimates of IFRs from countries like China, France, Brazil and Spain, which can provide some perspective to the numbers being recorded in India. If we assume a 20-million population and that 40% of the population has had the infection, Delhi should have had 40,000 deaths based on an IFR of 0.5%; 48,000 deaths based on China’s IFR; 56,000 deaths based on France’s IFR; and, 80,000 deaths based on Brazil’s or Spain’s IFR. But the reported number of deaths in Delhi, as pointed out, is only 3853 – this is an unbelievably low IFR by global comparison.

Which brings us to the question made popular by the media, ‘To what extent are Delhi’s COVID-19 deaths being underreported?’ Many ‘experts’ have tried to answer this question for different cities using data from cremation and burial grounds, more often than not coming to erroneous conclusions. New official data can perhaps shed some light on the issue. It is reported that ‘all-cause mortality’ in Delhi has gone down as per the Civil Registration System data for April-June 2020, compared to the same period in 2019. Between April and June 2019, a total of 27,152 death registrations were filed in Delhi. This year, during the same period, only 21,344 deaths were registered, including more than 3000 COVID-19 related deaths. By the absurd logic of the authors of The Washington Post article, this would mean that COVID-19 has had a positive effect on mortality in Delhi.

Beyond the Obvious

Nevertheless, data on death registration and causes of death are known to have inherent biases arising from inclusion or exclusion of certain categories of people, such as migrant workers or non-residents. In India’s case, it is known – and well-acknowledged – that such biases are larger than usual in States with medical hubs. In many such States, cities with medical hubs tend to have a higher number of registered deaths; sometimes well beyond the estimated number of deaths for the residents of the State. As a consequence, many States end up with more than 100% death registration.

The existence of good health infrastructure as well as an alert registration mechanism at the ground level has made sure that a large number of such ‘excess deaths’ happen in Delhi every year. This has been true for the last two decades. In 2018, the year for which the latest data is available, the number of ‘excess deaths’ in Delhi was a staggering 70,504. This amounts to an extra 94% on the estimated number of deaths.

So, Delhi’s death registration is a very high 194%. This should prompt further absurdities in the Western media.

The ‘excess deaths’ are accounted for by people who come to Delhi from far-flung areas in search of better care in public as well as private hospitals. Knowledge of these numbers perhaps pushed Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal to make his now infamous announcement in June that “outsiders” are no longer welcome in Delhi’s hospitals, as the city was bracing for the COVID-19 surge. Looking at Delhi’s death registration data for April-June 2020 shows that in any case, the lockdown had severely limited the number of patients coming to Delhi for treatment. This has been consequently reflected in the reduction of overall deaths recorded in the city. On the contrary, eyewitness accounts from doctors suggest that in Mumbai, even during the peak of COVID-19 mortality, patients from nearby regions were being treated in large numbers, perhaps leading to the spike in deaths registered in May, along with the registration of deaths from prior months.

The Way Forward

There are experts who believe that Delhi flattening the curve may just be a statistical artefact created by the new antigen testing method which leaves out a potentially large number of asymptomatic patients with lower viral loads. Even as asymptomatic patients moving around causing a silent spread and a future mortality load remains a theoretical possibility, the Delhi Government’s, the Union Government’s and the Municipal Corporation’s shift in focus to antigen testing, which offers almost instant results, seems to be based on sound epidemiological advice.

The results of Delhi’s as well as the just-released Mumbai’s seroprevalence survey results have shown that even in the middle of the strictest lockdown, the virus has been circulating freely, and hence a shift in policy focus from ‘containment’ to a widening of the net—by using a quicker if less accurate test—to catch those potential super-spreaders with a potentially high viral load in time, is justified. The objective now seems to be minimising deaths even further by avoiding possible delays in treatment, and, so far, it seems to be working in older hotspots.

However, this situation and the perceived herd immunity in parts of Delhi must not lead to a rapid opening up of the city, which could prove to be counterproductive. Firstly, the current low thresholds of herd immunity is directly linked to the relatively low R0 levels. If Delhi reopens quickly, new cases can quickly spike up, taking the R0 levels up, pushing the herd immunity threshold further up. Also, it is possible that death rates are low in Delhi because those getting infected up until now are predominantly the relatively younger, healthier population. A quick opening up may expose the high-risk populations, who are currently largely unexposed, which could result in a higher number of deaths.

Unless a cautious and systematic plan of reverse quarantine of the high-risk population, mixed with physical distancing, masks, hand-washing, and selective mobility control is put in place; taking the current decline in case and mortality load for granted would be disastrous. More direct, regular and honest public health communication is necessary. We cannot infantilise the population and hide information from them, believing that it is safer for them to not know the real numbers. Making the population aware of the risk and facilitating voluntary compliance to public health measures is a major function of a health system. Tragically, that remains the proverbial weakest link.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV