This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Technology as the Problem

In the 1960s, Rachel Carson’s powerful book ‘

The Silent Spring’ on environmental degradation and its impact on human lives convinced people that ‘the control of nature was a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man’. It was scarcely coincidental that the

environmental movement that followed the release of Carson’s book and the energy crisis occurred at the same time. They had common origins in rapidly increasing energy demand and even more

rapid depletion of oil and natural gas. On the production side, depletion of oil and gas reserves necessitated renewed reliance on coal, as well as oil & gas exploration in offshore and wilderness areas.

The accident of the nuclear reactor in Three Mile Island in 1979 and numerous oil spills between 1970 and 1980 was sufficient to convince the public that ‘technology’ was in fact the main cause of environmental degradation.

To combat rising production costs, technologies of scale were increasingly applied. The immense scale of the energy systems, their drain on energy resources, and the cumulative effects of their effluents evoked widespread academic debate over the possible

limits to growth by the Club of Rome study published in 1972. The accident of the nuclear reactor in

Three Mile Island in 1979 and numerous oil spills between 1970 and 1980 was sufficient to convince the public that ‘technology’ was in fact the main cause of environmental degradation. The environmental movement that was sustained in this period sought a radical social change in the form of increased self-determination, decentralisation of energy production and use, and decentralisation of decision making. This movement which appeared to threaten existing economic, institutional and social order has since been labelled ‘

eco-fundamentalism’ and marginalised to the fringes of society.

Technology as the Solution

The climate movement of today is less radical and more practical and policy-oriented. Rather than finding alternatives for society it is seeking to find alternatives within society in the form of technology to solve the problem of environmental degradation. The origin of this perspective can be traced to the report, ‘

Our Common Future,’ also referred to as the Brundtland Report released in 1987. It concluded that economic growth and environmental protection have to be made more compatible for humanity to have a positive future. ‘

Sustainable development’ was the label attached to this compromise between the economy and the environment, and since then humanity has looked upon technology to deliver this ideal state of affairs. This was projected as the logical choice given the difficulty in changing human behaviour to change the course of growth in population and affluence. Technological ‘fixes’, even if only temporary, were seen by the dominant environmental and climate groups as the only source of comfort and hope to take on the gloom that was forecast by climate studies.

Substantial improvement in energy use efficiency was achieved through the systematic application of technology and knowledge.

Technology has in fact played a key role in facilitating a 70-fold increase in global income (GDP, Gross Domestic Product) between

1800 and 2000 without a proportional increase in energy consumption and carbon emissions. In this period global energy use increased 35-fold, carbon emissions increased 20-fold, and the world’s population grew 20-fold. The sharp growth in population was overshadowed by the positive feedback loop of capital creating more capital and thus causing super-exponential growth in industrial output. Substantial improvement in energy use efficiency was achieved through the systematic application of technology and knowledge.

Cultural historian

Leo Marx argued that our inadequate understanding of the part played by ideological, moral, religious, and aesthetic factors in shaping a response to environmental problems makes us lean more on science and technology. The faith in scientific knowledge and technology is so strongly embedded in society that environmental problems are named after their biophysical symptoms such as ‘soil erosion’ or ‘acid rain’ and scientists and technologists are expected to provide solutions. Marx points out that if we as a society, were less technology-friendly, might have avoided the term ‘Greenhouse effect’ in favour of ‘

the problem of global dumpsites’. Social justice would have set the terms of the climate debate rather than economic and technological efficiency if ‘colonisation of the atmosphere’ had been the chosen term rather than ‘climate change’.

The technology-friendly environmental movement has facilitated the crossover of hard-core environmentalists of the 70s to become counter-experts who borrow from the same industrial structure that created a polluted and divided world. They project science, technology, and expert-led process as solutions to the environmental conflict whilst marginalising inherent social contradictions. A new course of scientific inquiry known as ‘

industrial ecology’ has been designed to marry industry and ecology so as to minimise the intensity of resource use in production and consumption. Under this course, the use of technology to reduce environmental impact can, in theory, not only compensate for more people but also the impact of more affluent people.

Challenges

The expectation from technology is that it will double the supply of energy and halve the level of emissions by 2050. In other words, ‘technology’ is expected to ensure that the current emissions track, which would see energy-related emission increasing to around

62 Gt CO2 (gigatons of carbon dioxide) in 2050, is reduced to half the level by 2050. Energy-related emissions alone must be reduced to just

14 Gt CO2 per year. The problem here is that most of the gains in emission reduction must come from developing rather than developed countries. More than

75 percent of the global growth in CO

2 emissions will originate from developing countries, with more than

50 percent from China and India alone. Halving emissions in OECD countries alone will yield only around 10 Gt CO

2 emission reductions needed.

Even if OECD emissions are reduced to zero, this would still only deliver up to

38 percent of the 48 Gt CO

2 emissions reductions needed. Key issues in this context are whether the optimism over technology is justified and how developing nations would pay for technologies that are owned predominantly by the private sector in developed nations.

No technology under development today is expected to rival these technologies in the next two to three decades unless their natural course of progress is interrupted by massive investment.

The answers to these questions expose some inconvenient truths. Energy technologies in use today such as the internal combustion engine and the steam turbine were invented in the 1880s, whilst nuclear power generation and gas turbines were invented in the 1930s. No technology under development today is expected to rival these technologies in the next two to three decades unless their natural course of progress is interrupted by massive investment. The cost estimates for dramatic interventions for technological shift vary widely. According to the IPCC, a

20-38 percent reduction in emissions can be achieved at a cost of US$50 per tonne of CO

2. The

Stern report gave an even more optimistic projection of a 70 percent reduction in CO

2 emissions by 2050 at the same cost. Empirical literature suggests that using current technology, the average abatement cost for a 70 percent reduction in carbon in the energy sector would be about

US$400 per tonne of carbon. Assuming that marginal costs of mitigation do not fall, the cost of emission reduction programmes is estimated at around

US$800 billion to US$1.2 trillion per year.

Under the egalitarian principle for cost sharing, large amounts of wealth have to be transferred from developed nations to developing nations. So far, developed countries have resisted this idea. The straightforward application of the equity principle will necessarily create winners and losers. Moreover, even when a country makes a case for the equity principle, it will be difficult to discern between the country’s concern with equitable burden sharing and its informed calculation of ‘national interest’.

Constructing a single formula that embraces the self-interest of both developed and developing nations is impossible. Dynamic graduation formulae on the other hand offer a degree of flexibility for balancing the growth concerns of developing countries against the concern of developed countries to expand participation and reduce leakage. For now, developed and developing nations have agreed on a graded burden sharing formula for what is essentially a technocratic response to climate change. This will postpone, but not eliminate the need for a social and political response to the environmental problem. Technology which appears to be rational and efficient, has often been short sighted as it tends to betray the future for the sake of the present.

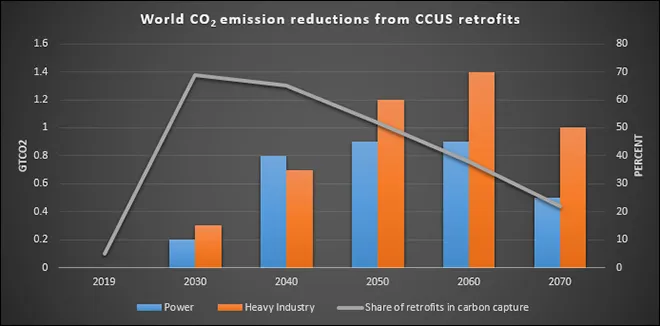

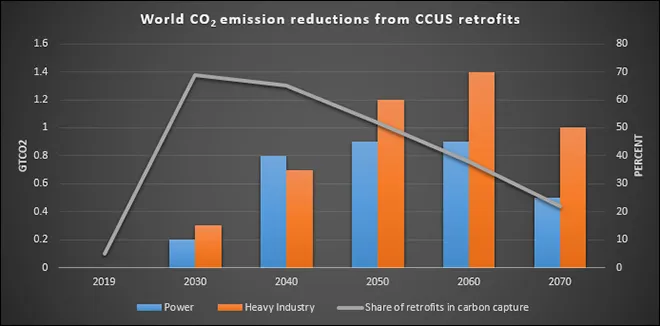

Source: International Energy Agency, Energy Technologies Perspective 2020;

Source: International Energy Agency, Energy Technologies Perspective 2020;

Note: CCUS: Carbon capture, utilisation and storage

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV